Audible sample

Audible sampleFollow the Author

Younghill Kang

+ Follow

East Goes West Kindle Edition

by Younghill Kang (Author), Sunyoung Lee (Editor, Afterword), Alexander Chee (Foreword) Format: Kindle Edition

4.4 out of 5 stars 24 ratings

"A wonderfully resplendent evocation of a newcomer's America" (Chang-rae Lee, author of Native Speaker) by the father of Korean American literature

A Penguin Classic

Having fled Japanese-occupied Korea for the gleaming promise of the United States with nothing but four dollars and a suitcase full of Shakespeare to his name, the young, idealistic Chungpa Han arrives in a New York teeming with expatriates, businessmen, students, scholars, and indigents. Struggling to support his studies, he travels throughout the United States and Canada, becoming by turns a traveling salesman, a domestic worker, and a farmer, and observing along the way the idealism, greed, and shifting values of the industrializing twentieth century. Part picaresque adventure, part shrewd social commentary, East Goes West casts a sharply satirical eye on the demands and perils of assimilation. It is a masterpiece not only of Asian American literature but also of American literature.

Celebrate Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month with these three Penguin Classics:

America Is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan (9780143134039)

East Goes West by Younghill Kang (9780143134305)

The Hanging on Union Square by H. T. Tsiang (9780143134022)

Read less

Print length

429 pages

Language

May 21, 2019

File size

===

Opening Credits00:21

Foreword by Alexander Chee10:58

Part 100:00

Book One00:04

Chapter 105:29

Chapter 205:34

Chapter 307:00

Chapter 412:07

Chapter 511:38

Chapter 609:21

Chapter 709:28

Chapter 807:45

Chapter 903:29

Book Two00:03

Chapter 115:15

Chapter 207:45

Chapter 306:01

Chapter 410:59

Chapter 508:16

Book Three00:03

Chapter 108:20

Chapter 209:24

Chapter 305:31

Chapter 404:20

Chapter 512:11

Chapter 602:27

Book Four00:03

Chapter 105:03

Chapter 202:35

Chapter 311:44

Chapter 414:12

Chapter 501:04

Chapter 606:37

Part 200:00

Book One00:05

Chapter 109:25

Chapter 202:38

Chapter 303:46

Chapter 402:26

Chapter 505:34

Chapter 605:28

Chapter 708:11

Book Two00:02

Chapter 121:04

Chapter 205:17

Chapter 307:52

Chapter 412:42

Chapter 504:33

Chapter 606:27

Book Three00:03

Chapter 111:10

Chapter 211:57

Chapter 303:49

Chapter 412:37

Chapter 508:03

Book Four00:03

Chapter 103:49

Chapter 207:52

Chapter 307:51

Chapter 405:14

Chapter 513:47

Book Five00:03

Chapter 102:30

Chapter 210:16

Chapter 307:21

Chapter 402:56

Chapter 508:34

Chapter 615:55

Chapter 705:15

Chapter 807:10

Book Six00:03

Chapter 122:26

Chapter 206:49

Book Seven00:03

Chapter 101:29

Chapter 207:18

Chapter 310:28

Chapter 407:57

Chapter 517:36

Chapter 623:14

Chapter 703:04

Book Eight00:02

Chapter 113:52

Chapter 218:25

Chapter 308:45

Chapter 426:16

Chapter 508:29

Chapter 607:03

Book Nine00:03

Chapter 119:20

Chapter 207:36

Chapter 321:10

Chapter 405:33

Part 300:00

Book One00:05

Chapter 140:27

Chapter 213:49

Book Two00:02

Chapter 110:12

Chapter 210:53

Chapter 315:06

Chapter 423:29

Book Three00:02

Chapter 116:32

Chapter 211:45

Chapter 314:53

Chapter 411:17

Book Four00:03

Chapter 122:25

Chapter 218:46

Chapter 306:32

Chapter 417:52

Chapter 504:53

Afterword: "The Unmaking of an Oriental Yankee" by Sunyoung Lee52:28

End Credits00:58

Picking up from where you left off

===

Customers who bought this item also bought

Page 1 of 8Page 1 of 8

Previous page

Yokohama, California (Classics of Asian American Literature)

Toshio Mori

4.8 out of 5 stars 16

Kindle Edition

1 offer from AUD 24.22

Eat a Bowl of Tea (Classics of Asian American Literature)

Louis Chu

4.0 out of 5 stars 24

Kindle Edition

1 offer from AUD 24.22

Not Without Laughter (Dover Thrift Editions: Black History)

Langston Hughes

4.7 out of 5 stars 585

Kindle Edition

1 offer from AUD 1.37

The Nine Cloud Dream

Kim Man-jung

4.6 out of 5 stars 107

Kindle Edition

1 offer from AUD 13.83

Dictee

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha

4.4 out of 5 stars 94

Kindle Edition

1 offer from AUD 17.99

No-No Boy (Classics of Asian American Literature)

John Okada

4.7 out of 5 stars 499

Kindle Edition

1 offer from AUD 20.76

Next page

Editorial Reviews

Review

“A Nabokovian stylistic tour de force.” —Alexander Chee, author of The Queen of the Night and How to Write an Autobiographical Novel

“The story of Chungpa Han is truly, like the old New York he encounters, as ‘million-hued as a dream.’ A wonderfully resplendent evocation of a newcomer’s America, Younghill Kang’s classic novel is as vibrant and pointed in its vision today as it was 60 years ago, and may prove to be one of our most vital documents. East Goes West deserves rediscovery.” —Chang-rae Lee, author of Native Speaker

“Thrillingly timeless . . . The finest, funniest, craziest, sanest, most cheerfully depressing Korean-American novel . . . A vast, unruly masterpiece that is our earliest portrait of the artist as a young Korean-American . . . East Goes West’s tumbling prose and loose, picaresque structure feel amazingly ‘free and vigorous’ (per [Thomas] Wolfe) today. . . . The novelist and memoirist Alexander Chee’s rousing introduction to the new Penguin Classics edition . . . argues strongly for its relevance today. . . . Its value is in the heady mix of high and low, the antic yet clear-eyed take on race relations, the parade of tragic and comic bit players, and above all, the unleashed chattering of Chungpa’s distinctive voice. . . . The Penguin edition . . . reminds us of how excellent [Kang] really was. . . . This brash modernist comic novel still feels electric.” —Ed Park, The New York Review of Books

“Kang is as wide awake and high-spirited as he is scholarly and thoughtful, and he writes with a keen sense of character. . . . East Goes West offers a rich largesse of color and flavor, personality and impression and event. It is one of those rare books which will arouse interest, ring changes on laughter and leave its residue of thought.” —The New York Times Book Review

“An immigrant epic that criss-crosses a less-than-welcoming American landscape . . . Thirty-year-old bestseller The Joy Luck Club perennially provides irrefutable proof Asian American stories warrant shelf space. That Penguin Classics—their venerable list considered a significant barometer of what comprises the Anglophone literary canon—has added this . . . is, undoubtedly, long-awaited, long-deserved recognition.” —The Christian Science Monitor

“Kang is a born writer, everywhere he is free and vigorous: he has an original and poetic mind, and he loves life.” —Thomas Wolfe

“After Mr. Kang, most books seem a bit flat. . . . What a man! What a writer!” —Rebecca West

“Here is a really great writer.” —H. G. Wells

“[Kang is] the father of Korean American literature. . . . East Goes West is a stunning testament to [his] indomitable spirit, his perspicacious eye, and his special mirth. The book provides us with a rare view of how urban American life was experienced—and critiqued—by Korean immigrants in the 1920s. Sunyoung Lee’s afterword . . . offers original insights into what she calls Kang’s ‘acrobatic talent for mediation’ between ‘the faltering traditions of . . . Korea and the seductive promise of American modernity.’” —Elaine Kim, co-author of East to America: Korean American Life Stories

“Whitmanesque in scope,Younghill Kang’s East Goes West attempts both self-realization and comprehension of all of America. But an undercurrent of sadness haunts this story of a young man’s heroic American odyssey—the sadness of ‘exiled’ Korean men stranded between two worlds, living out their lonely lives on the periphery of American society, working in menial jobs far beneath their education.” —Kichung Kim, author of An Introduction to Classical Korean Literature

“Unique and vividly realized . . . In its portrait of a young man’s fracturing idealism, it is also an extraordinary, if coded, critique of American materialism.” —Sunyoung Lee, from the Afterword

“Groundbreaking and inspirational . . . A call to action, a call for the country to live up to the dream it has of itself . . . This book is for all of us.” —Alexander Chee, from the Foreword

About the Author

Younghill Kang (1903-1972) was born in what is now North Korea and emigrated to the U.S. in his late teens. He studied at Boston University and Harvard and published widely in such outlets as The New York Times and The Nation. While teaching English at New York University, he was introduced by fellow professor Thomas Wolfe to legendary Scribner's editor Maxwell Perkins, who would publish Kang's books. Kang was the first Asian to be awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship; he would be awarded two in his lifetime, among his many other honors.

Alexander Chee (foreword) is the bestselling author of the novels The Queen of the Night and Edinburgh and the essay collection How to Write an Autobiographical Novel. His work has appeared in The Best American Essays 2016 and The New York Times, and he is a contributing editor at The New Republic. The winner of a Whiting Award, he is an associate professor of English and creative writing at Dartmouth College. He lives in New York City.

Sunyoung Lee (afterword, notes) is the publisher and editor in chief of Kaya Press, which specializes in literature from the Asian and Pacific Island diasporas. She lives in Los Angeles. --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

Read more

Product details

ASIN : B07GV4MFD7

Publisher : Penguin Classics (May 21, 2019)

Publication date : May 21, 2019

Print length : 429 pages

Best Sellers Rank: #377,776 in Kindle Store (See Top 100 in Kindle Store)

#189 in Historical Japanese Fiction

#364 in Historical Asian Fiction

#443 in Asian American Literature (Kindle Store)

Customer Reviews:

4.4 out of 5 stars 24 ratings

Younghill Kang

Customer reviews

4.4 out of 5 stars

4.4 out of 5

24 global ratings

Top reviews

Top review from the United States

Spike

2.0 out of 5 stars Fails as fiction, fails as memoirReviewed in the United States on May 11, 2020

The narrator of the book offers an extraordinarily shallow set of observations, and no character is developed beyond him. While the narrative choice is fascinating--a Korean in the USA in the 1920's-1930's--the book fails as fiction and memoir. Weighing in at 362 pages, it would have benefitted from an editor who could have distilled it into about 112 pages, and made it a truthful memoir. As it is, there is a bountiful of detritus, meaningless detail, incomplete portraits of people and things, and a stunning, ironic lack of introspection. It is unimaginative. This is extremely disappointing when one considers that the book could have been a great exploration of a critical missing piece of US culture: The inner life of Asian immigrants, and the political and social struggles faced by these communities that built so much of the country.

7 people found this helpful

HelpfulReport abuse

East Goes West: The Making of an Oriental Yankee

by Younghill Kang

3.82 · Rating details · 179 ratings · 27 reviews

This is a new edition of a classic and long unavailable text by Younghill Kang, the first Korean-American novelist. Younghill Kang was born in 1903 in what is now North Korea and arrived in New York in 1921. He continued his studies at Harvard and built a name for himself as a scholar of literature and Asian culture and as an author. His fiction was admired by, among others, Pearl S. Buck, H.G. Wells and Thomas Wolfe. Originally published in 1937, East Goes West met with widespread acclaim despite its biting portraits of racism, alienation and hypocrisy at every level of American society. This eagerly anticipated edition includes informative appendices detailing the author's life and writings, including primary source materials that provide insight into the relationship between Kang and his editor, Maxwell Perkins. (less)

GET A COPY

KoboOnline Stores ▾Book Links ▾

Paperback, 425 pages

Published February 2nd 1997 by Kaya/Muae (first published 1937)

More Details...Edit Details

EditMY ACTIVITY

Review of ISBN 9781885030115

Rating

1 of 5 stars2 of 5 stars3 of 5 stars4 of 5 stars5 of 5 stars

Shelves to-read edit

( 1315th )

Format Paperback edit

Status

March 7, 2022 – Shelved as: to-read

March 7, 2022 – Shelved

Review Write a review

comment

FRIEND REVIEWS

Recommend This Book None of your friends have reviewed this book yet.

READER Q&A

Ask the Goodreads community a question about East Goes West

54355902. uy100 cr1,0,100,100

Ask anything about the book

Be the first to ask a question about East Goes West

LISTS WITH THIS BOOK

Please Look After Mom by Shin Kyung-sookPachinko by Min Jin LeeThe Vegetarian by Han KangWhen My Name Was Keoko by Linda Sue ParkHuman Acts by Han Kang

Fiction by Korean Authors and/or Containing Korean Characters

388 books — 397 voters

The Joy Luck Club by Amy TanInterpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa LahiriUnaccustomed Earth by Jhumpa LahiriThe Namesake by Jhumpa LahiriCutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese

Immigrant Voices (fiction)

349 books — 254 voters

More lists with this book...

COMMUNITY REVIEWS

Showing 1-30

Average rating3.82 · Rating details · 179 ratings · 27 reviews

Search review text

All Languages

More filters | Sort order

Sejin,

Sejin, start your review of East Goes West: The Making of an Oriental Yankee

Write a review

David

Aug 16, 2019David rated it really liked it

I'm gob-smacked after reading this.

I mean more than the fact I ended up enjoying this story of Chungpa Han coming to the US in the 1930s from Korean with only four dollars in his pocket and a suitcase full of Shakespeare. That he portrays an America populated by immigrants; Koreans, Chinese, Italians, Russians helping each other out. That it's a sharp commentary on the "American Dream" and it reads like something that's always been a part of the canon.

And I'm floored that I've never read this before, that Amy Tan would be my first experience with an Asian-American writing about-Asian Americans. That Chang Rae Lee would be my first encounter with a Korean-American author years later. And here was Younghill Kang writing decades earlier.

And that's what absolutely kills me. Younghill Kang taught English at New York University with Thomas Wolfe. Wolfe would introduce him to Maxwell Perkins at Scribner who published his works. Kang dined with Hemingway and Fitzgerald. And while they have become part of the popular consciousness with countless movie adaptations of The Great Gatsby, pilgrimages made to the bars Hemingway wrote in, and even a movie treatment, called "Genius" telling the story of Perkins and Wolfe - Kang doesn't even warrant a footnote.

This is a huge work that deserves wider recognition. As Alexander Chee remarks in the foreword to the new Penguin Classics edition "He is one of those writers whose work has influenced you even if you’ve never read him." Expand your literary canon and take in a new perspective from what should be a recognized voice in American letters. Video review here: https://youtu.be/yiEBa_RDxAo (less)

flag34 likes · Like · 3 comments · see review

Alwynne

Jul 10, 2021Alwynne rated it really liked it · review of another edition

Shelves: fiction, korea-fiction-culture-history

The varied adventures of a young Korean exile Chungpa Han combine to produce a wonderfully understated, absorbing critique of American society in the 1920s and 30s. Through Han’s eyes the brash commercialism and rampant materialism that underpin this era of rapid change are persuasively represented from get-rich-quick schemes and exploitative business owners to the turbulent experiences of the country’s segregated, immigrant communities. Younghill Kang’s semi-autobiographical novel has no real plot, instead it follows his central character Chungpa Han, in self-imposed exile from Japanese-occupied Korea, as he lurches from one setting to another trying to find a place for himself in an overwhelming, new world. Han starts out in New York with a few dollars and a lot of books, his ambition’s to study and build on his intense love of literature from classical Chinese poetry to Swinburne and Shakespeare. He grapples with racism and isolation but he also finds pockets of acceptance and unexpected friendship.

Kang meticulously reconstructs the bustling atmosphere of the age – the scenes of Greenwich Village bohemia, Harlem and New York’s Chinatown are particularly striking and vivid. Kang shared an editor with his friend Thomas Wolfe, so probably not surprising to find the occasional Wolfean flourish invading his prose but fortunately the majority of Kang’s narrative’s given over to quietly perceptive character studies and rich description. His hero Han’s outwardly self-effacing, forever placing himself in the background, but he’s not some version of Isherwood’s passively recording camera, his observations are laced with pointed, sometimes lacerating, comparisons between Korean and American culture and values. There are moments when the level of detail can be a bit overwhelming, and this is possibly more significant for what it offers in terms of cultural and social history than for Kang’s conventional writing style, but even so I was completely caught up in it. (less)

flag29 likes · Like · see review

Krista

Apr 08, 2019Krista rated it really liked it · review of another edition

Shelves: 2019, arc, koreas

We floated insecurely, in the rootless groping fashion of men hung between two worlds. With Korean culture at a dying gasp, being throttled wherever possible by the Japanese, with conditions at home ever tragic and uncertain, life for us was tied by a slenderer thread to the homeland than for the Chinese. Still it was tied. Koreans thought of themselves as exiles, not as immigrants.

Out of print for the past fifty years, East Goes West is being rereleased in May 2019 for Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. A semi-autobiographical account of a young man's experiences after coming to America from Japanese-controlled Korea in the late 1920's, this book is considered the first true Korean-American novel, and as such, serves as a colourful snapshot of its time and place. In addition to the restored text, this edition includes a chronology of author Younghill Kang's life, suggestions for further reading, a useful foreword by author Alexander Chee, and an edifying afterword by Sunyoung Lee (Editor and Publisher of Kaya Press). It is Lee who explains that in its day, although well-received, many reviewers dismissed East Goes West as “merely memoir”: Kang the writer is replaced by Chungpa Han the character, and in the process, Kang becomes an early victim of the still-prevalent belief that the only contribution any writer of color could possibly have to make is the story of his or her own life. Lee counters: Kang staked out his literary tradition very clearly: the book was to be both a novel of ideas and the portrait of an era. The issues he proposed to address might not have been strikingly innovative in and of themselves, but they were to be explored from the unique perspective of an Asian living in the U.S. with access to the literary, philosophical, and social conceits of two traditions. Especially through this lens, East Goes West is a masterwork – I found it much more readable than other books from its era – and I am grateful that it has been brought back from the dead. (Note: I read an ARC and passages quoted might not be in their final form.)

New Yorkers seem to have some aim in every movement they make. (Some frantic aim.) They are like guns shooting off. How unlike Asiatics in an Oriental village, who drift up and down aimlessly and leisurely! But these people have no time, not even for gossiping, even for staring. To be thrown among New Yorkers – yes, it means to have a new interpretation of life never conceived before. The business interpretation...Free, factual man is reasoning from cause to effect here all the time – not so much thinking. It is intelligence measuring, rather than intellect's solution. Prophets of hereafter, poets of vision...maybe the American is not so much these. But he is a good salesman, amidst scientific tools. His mind is like Grand Central Station. It is definite, it is timed, it has mathematical precision on clearcut stone foundation. There may be monotonous dull repetition, but all is accurate and conscious. Stupid routine sometimes, but behind it, duty in the very look. Every angle and line has been measured. How solid the steel framework of this Western civilization is!

At eighteen years old, with four American dollars and a suitcase full of Shakespeare, Chungpa Han arrives in New York City with hopes of continuing his studies of Western literature. He meets many helpful emigrants from various Asian countries in the city's bustling Chinatown, but it is to other ex-pat Koreans that Han is primarily drawn; and it is from them that he receives the best advice and aid. Over his ensuing collegiate career, Han will work as a houseboy, a farmhand, a door-to-door salesman – and in every situation he will encounter goodness and racism, always managing to get by and not cause waves. Kang is careful to have other characters make all the dramatic gestures and opinionated speeches – Han rarely gets passionate outside of intimate discussions of art and literature – and while this makes the main character seem passive and submissive, his inner thoughts show a progressive development from naive to cynical. By the end of the novel, despite having completed his education (in and out of school), settled into his working career and a hint at romantic fulfillment, Han muses:

All lives rise from nature, express it a moment, then come to destruction in the undying world – the scientist with his laboratory invention, the explorer with his passion for the undiscovered land, the mother with her devotion of love, the lover with heaped agony, all doomed and destined to be ashes under the volcanic destruction of death, as Pompeii under Vesuvius. It is all a matter of how soon. Life the eternal butterfly flutters into its natural web. Yes, the philosopher, too, dreaming he may be that butterfly, moves on to his death, and only the undying universe remains, the bird of two wings.

I had never considered the early Korean-American experience before (closer to home, Han spends some time in a small Canadian college and pretty accurately dismisses it as a backwater both yearning to be British and at least a generation behind American progress), and East Goes West was an interesting and educational read. There are some irony-laden funny parts (especially Han's time with the millionaire evangelist), some quasi-racist observations that, while they may reflect Kang's thoughts in the '30s, don't weather the intervening years well, and much thoughtful commentary on the East vs the West. Not a book to get through quickly, I'm happy to have received this one for review; hope it finds a new audience. (less)

flag13 likes · Like · comment · see review

Michael

Apr 22, 2020Michael rated it it was ok

What a grind. Over the course of a couple greatly distracted weeks of reading I read through this picaresque novel about a Korean in exile in America back when there were basically no Koreans here. What I thought would be some flowing and episodic adventures and a tale of real adversity turned out to be a disappointing slough of aimless modernity. (But can I really judge it too harshly for not conforming to my clueless notions of what this experience could be like?) Though the narrator does progress in his understanding of the West, shedding much naivety and learning a great deal about Western philosophy, religion, culture, and industrial economics, his travels, odd jobs, and social outings never add up to anything more than their own recollections. On the plus side, Kang makes a rather concerted and successful effort at chipping away at the farcical edifice of the American Dream, exposing its elusiveness, vacuity, and manifold privileges at every turn. He frequently juxtaposes East and West, Confucianism and Protestantism, obedience and freedom, arrangement and love, all of which probably leads to some interesting reckonings for most Western readers. However, this autobiographical novel is actually at its best when Kang builds up a sense of immigrant and minority solidarity in a land working against their success and when he holds up a mirror for Western readers to look at themselves in a new light. This seminal author—one of the very first Korean-Americans to be published—seems to have some dated, unhurried, and rather arduous writing, yet it is not without worth by any means. (less)

flag4 likes · Like · comment · see review

V

Dec 24, 2017V rated it it was amazing

A lot in here to think about. A lot in here that is as relevant today as it was then. Identity. Ambivalence with assimilation. Being without and between countries. Craftsmanship of persona. The need for belief, and for hope. The audacity of personal belief, and belief in country, and to keep moving forward in that belief -- even when it has been shaken. Rebirth into a new frame of mind and sense of living/self. Who can you be between who you know you are, and can be, and wish to continue being, versus who you are allowed to be? Slow-reading. Thankful to have it. (less)

flag3 likes · Like · see review

Kelly

Oct 10, 2018Kelly rated it liked it

The way the story is told is chronological but it's almost as if he tells his own personal narrative passively. The way he interacts with people in his life is awkward and I am not entirely sure if it was autobiographical completely or also fictionalized. Just not my favorite, but the first book for class so let's see if the other ones we read are better. (less)

flag3 likes · Like · comment · see review

Joy

Feb 17, 2021Joy rated it really liked it · review of another edition

Shelves: netgalley-reviews

Penguin classics brings a tale of immigration and exile to a new era and to readers who are acutely attuned to the complexities thereof. While East Goes West is most often seen as thinly veiled autobiography, Sun-young Lee warns of reducing it to this view in the essay that serves as afterword to this edition. Indeed, Kang is the poet he claims to be and gives the narrative so much more than an assimilation plot line. The myriad characters and interactions in a variety of urban and rural settings provide opportunities for contemplations not just on the America of the 1930s, but of what it means to claim one’s identity and the roles of economy, race, and class in that process. The place of the academic and the artist in such a vibrant setting is a question that appears throughout the work. Although it has not had a place of prominence in American literary studies for sometime, East Goes West is a brilliant piece that may be overdue for the limelight.

Thank you to the Penguin Group and NetGalley for an Advance Reader Copy in exchange for an honest review. (less)

flag2 likes · Like · see review

Taiyo

Mar 29, 2021Taiyo rated it really liked it

The new Penguin version has some excellent essays by Alexander Chee and Sunyoung Lee that do a wonderful job framing Younghill Kang to our current context.

It would be a really fascinating pedagogical practice to pair, celebrate and contrast this with Carlos Bulosan's America is in the Heart, for he and Kang are the pioneering voices of Asian American literature. They are 2 vastly different individuals with 2 remarkable lives and illuminating books that show us the underbelly of early 20th century America. In these texts, both arrive to the idea of a somewhat fluid but ultimately cut throat racial caste system in the US where Asian migrants toil in spaces with other migrants and people of color, yet both arrive to this idealism of what America can be, despite all the horror these stories display. More can be said about the colorism within Asian folks to analyze their different lived experiences, as well as how some stories reflect these contrasts. To use a Cornel West phrase, they were both, "prisoners of hope" and despite the writers' varying levels of assimilation into their societies, all stuck to a dream of America that if it didn't accept them at the time, they believed that one day it could be as just, inclusive and equitable as they envisioned. The jury is still out on this one, but we can work and read for that hope. (less)

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Adeel

Feb 24, 2021Adeel rated it liked it · review of another edition

East Goes West by Younghill Kang was an insightful, often funny and interesting story that focuses on a young man's journey experiences throughout America and Canada after having arrived from Korea during the 1920's. The book was actually first published in 1937 and the copy I was lucky enough to receive is the first republished copy in over 50 years!

The story is a semi autobiography of Younghill Kang but he is replaced from the POV of a fictional man called Chungpu Han. Han first sets foot on America after arriving in New York with 4 dollars and the works of Shakespeare in his suitcase. At this point in his life he is 18 and ready to absorb all that he hopes he can gain in America. It's not all plain sailing for Han as he has a torrid time trying to accustom himself to America. For example, Han has a letter of introduction to the Y.M.C.A. given to him by a missionary. The naïve Han is made to believe that is his golden ticket to riches and prosperity. Upon arriving at the main office of the organisation he is told to go to Harlem. There he deals with racism first hand as he is told no Orientals or Africans can be employed at the Y.M.C.A.

Having unwittingly spent all of his money on a haircut and clean shave, Han finds himself having to go to a "flophouse" a place that offers very low cost housing. Although jobless and left without any direction as to where his life will end up going, this doesn't stop Han from continuing to discover the American Dream. He has known poverty before so it only gives him a "it can not get any worse than what I've known".

"So far I had failed in everything undertaken in America. Housework, clerking, wait ing, in nothing was I good. It remained to be seen if I could rem edy this by education."

There are many times Han is struggling to even get something to eat, sometimes even going 24 hours without eating or drinking. Luckily for Han, he befriends many immigrants and outcasts like him New York. Immigrants from Korea, Italy, China, Japan, and the Philippines. Many of these friends like him are or have struggled to assimilate to life in America. However, even with their struggles they are still able to aide him and save him from starvation. It was actually really heart-warming seeing the generosity of people. The world then and now is definitely a dog eat dog world, so receiving even a little bit of help can go a long way.

Much of the help Han gains and essentially helps him learn about what it means to be American come from Korean exiles like himself such as George Jum who to a certain extent was Hans Guru. George a playboy who has absorbed everything that is American culture putting behind what he was accustomed to in Korea.

"The next period of my life must properly be dedicated to George Jum. He attempted to be my teacher in things American, and certainly he had left all Asian culture behind as a thing of nought. If I am not a very shining example of his precepts, the faults must be laid to me and not to him."

Later however, having failed to keep down a job we see Han travel to Canada in the hopes of clearing his path towards success. Thanks to a Canadian missionary called Mr Luther who was the headmaster of a Korean school where Han has completed his post graduate degree, he is told a scholarship is open to him in the Maritime University up in Canada. He meets great tutors such as Ralph and Ian. From his experience in Canada he discovers it as essentially as a bootleg Britain and really needs to catch up with America in terms of its development.

"Marvellous how this noisy coloial town could still convey obliquely an Old-World pattern, reminding of the English home."

He then finds himself in Boston where he becomes a salesman and then returns to education. This becomes somewhat of a pattern for Han throughout the book i.e. working for a bit then returning to college. He makes more friends and acquittances there and begins to settle down. Long story short, he finishes his education gaining a diploma from Boston, finally settles into a regular job , and even a wee romance blossoming. Still however Han never managed to gain a feeling of self fulfilment, even being partially jealous of George Jum.

When considering the writing, it was very descriptive and so detailed reminding me of the great Haruki Murakami. I'm going to be honest however and say reading this was a bit of a grind. Han's POV is very philosophical which meant some parts went on and on. I do feel the novel could've been cut down by 100 pages. However, Kang does describe characters and places in such amazing detail that you can't help but be in awe.

There are also many funny moments throughout the book, i think my favourite was definitely Han's being an atrocious houseboy. Kang also covers issues he faces and observes along his travels throughout Canada and the USA such as racism and stereotyping towards oriental people. I would however go far as saying that the character of Han was a bit of a racist himself due to how he stereotypes those from an African background and the use of racial slurs. It was very uncomfortable for me if i am very honest and i do understand that a book written during the 1930's didn't think about these things back then but still it annoyed me.

One final thing I really enjoyed was the array of different characters Han meets throughout America and Canada. Although some are only part of the story for a short time, they all played a key role in Han's experiences and his reflections of being a Korean immigrant in America during the 1930's. Han is very observational and describes the people he meets with such intricate detail that you can picture them in your mind.

Overall, this book was a grind to get through but I do feel it was worth reading. I learned a lot about the history and journey of Koreans living in the USA. The writing was also very descriptive and detailed, but at times I felt it was too much and went on a bit too long. This is worth reading but a lot of patience is required for sure.

Thank you to Viking Books, Penguin Random House, and Penguin Classics for gifting me a copy. I am very grateful for the opportunity #PRHparter (less)

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Janet

Jan 30, 2021Janet rated it really liked it

I read an old version of this book from 1937, so I am not sure if my copy was missing a part. My copy is either missing that part or it was numbered incorrectly. We went from losing contract to Trip in the end of book 2 to saying that he became a vagabond in book 4. Was there something in between?

I borrowed a new version of the book. As it turns out, the parts were mis-numbered in the earlier version. Now I get to read the Foreword and Afterword!

It's a remarkable novel. The ending is amazing. I ...more

flag1 like · Like · 1 comment · see review

JoshD7

Jan 13, 2020JoshD7 rated it it was amazing

East Goes West is surely an interesting book. That isn’t to say that this book is particularly bad, however it is certainly a niche book. This book does a fantastic job in what it intends to do, an exploration of American culture, society, and economics from a classical Korean perspective. The plot structure of the book, a collection of chronological short stories, does well to give the book a more meaningful experience, making the reader feel more connected with Han, the stand in for Kang. This element is one that I much appreciated as it gave the book an interesting “plot” that could be followed along with ease, and one that helped to show the growth in Han’s character.

This book also excels in characterization. Kang describes the characters in his book with the same length and detail as Tolkein. These deep dive descriptions increase the readers involvement in the lives of the characters and by extension the novel as a whole. Perhaps the most prevalent element of Kang’s story, the extensive use of figurative language and references to classical literature, is a true make or break for this book. Personally I appreciated the inclusion of such material for it gave a much more advanced level of understanding towards the stories Kang was telling. This, however, could be quite the opposite for someone else. Kang’s book is full to the brim with high level writing, thus demanding a high level of comprehension, something that not all can appreciate. I would recommend this book to a patient reader, one who values the slow and eloquent story which implies more than it states. Someone who enjoyed Of Mice And Men may find this book to be about right for them. All in all East Goes West is a fantastic novel in the area it inhabits, and I certainly enjoyed my time reading it.

(less)

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Laura

Jun 30, 2019Laura rated it really liked it · review of another edition

"First Korean American novelist." This book was written in 1937. Main character has fled Japanese occupied Korea for the US. He travels through the US and Canada struggling to keep up with his studies. I quote, "...a sharply satirical eye on the demands and perils of assimilation and offers biting portraits of racism, alienation, and hypocrisy at every level of society."

Detailed. Took some time to get into the rhythm of the story, but worth reading. ...more

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Charlotte

Jun 29, 2019Charlotte rated it really liked it

A slow, ponder of a wander through the immigrant's America. America, and all the ways it fails to live up to the American dream, seen through an early Asian immigrant's eyes. Dense and plodding, without much of a story, but observant, keen, and acute. Forces upon you an awareness of all the ironies interwoven into America and the ideals it supposedly embodies. Humorous, poetic, but sometimes dull and a chore to read. (less)

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Justin

Jul 15, 2021Justin rated it liked it · review of another edition

Shelves: classics, literary-fiction

I usually avoid reading anything published before the 1950s due to stylistic preferences as a lazy modern day reader. However, after reading Chang-rae Lee's Native Speaker, I was surprised to discover the first Korean American novel published in 1937. I picked up the Penguin Classics edition, and was fascinated with the bonus intro, afterword, and timeline of Younghill Kang's life. That being said, Kang's second novel East Goes West is semi-autobiographical, following the story of Chungpa Han who escapes Japanese-occupied Korea for New York with only four dollars in his pocket and a suitcase full of Shakespeare. Like many immigrants, Chungpa is drawn to the American Dream, and longs to study and be a scholar of classic literature. Initially naive and idealistic, Chungpa must support his studies through various jobs as his travels take him throughout the US and even Canada. While he works as a dishwasher, housekeeper, farmer, travelling salesman, retail worker, and editor, he meets people from all walks of life and of all colors, all while observing and discovering the reality of America.

As a whole, East Goes West is a dense read with thought-provoking examinations about racial identity and a deconstruction of the American Dream. Chungpa as a character is more of a fly-on-the-wall, which works given his outsider status. Initially, everything is new to him, he even finds living in a flophouse or being treated in a demeaning way as a housekeeper as amusing. Despite the satire, the book highlights the struggles of immigrants, and how survival supersedes all other idealistic desires. Yet Chungpa is adamant to overcome these barriers, namely with race as he tries to break into the academic scene. On the way, he meets two fellow Koreans who offer different points of view about America: George Jum with his modernist idealism and To Wan Kim and his cynical and equally critical view of both East and West. As Chungpa discovers with his interactions with blacks, America is still very much a caste system. And as an Asian, he occupies a unique position, invisible, yet out of place, but at the same time, in the same position as other minorities. The book ends ambiguously, yet highlights the disillusionment Kang likely arrived at in his own life as a first generation Asian American. Overall, while East Goes West wasn't consistently engaging, it's a classic, yet relevant book for today's Asian Americans. (less)

flagLike · comment · see review

Nick

Jun 24, 2021Nick rated it really liked it · review of another edition

Shelves: historical, literary, international, memoir

The first sucessful Asian-American novelist, Kang delivers a charming, thoughtful and beautifully written bildungsroman with a twist, namely he is a Korean trying very hard to find his way in North America in the 20s. His narrator arrives in New York City with almost no money, via Canadian missionaries just as Korea is colonized by Japan, and just before the USA clamps down on Asian immigration. Along the way the protagonist encounters and befriends a dizzying array of character types, most all roundly satirized, especially those associated with capitalism. The guy is a proto-socialist. Included are academics, entrepreneurial sales maniacs, religious flim-flam men, as well as a variety of Asian pals with various responses to the West, from assimilation to resistance. Our hero is torn between cultures, equally in love with the deep culture-embued scholarship of traditional Confucian poets and the riches of the Euro-centric cultural canon, especially Shakespeare and Browning. As much as an autobiographically-tinged novel, this work is a humanized exploration of ideas. (less)

flagLike · comment · see review

Wendyjune

Oct 10, 2019Wendyjune rated it it was amazing

I loved this book. It is dense and full of detail, I had to read it in nibbles at first. Kang seemed to understand the density, it is put together in a way that makes it chewable, with small bursts of books and sub-books. That is the format. The writing is something else.

It is honest, filled with emotion without being emotional. The cold hard facts speak loud enough. The cost of things, the language, the clothes and the environments are described perfectly, showing instead of telling about racism, wealth, religion, philosophy, poets, writers and the exile experienced in unknown cultures. His first day off the boat is incredible!

He is the ultimate observer. Finding this book has felt like an impossible quest, but I had been looking for a book like this for quite sometime, and I found it sitting perky on a library shelf.

(less)

flagLike · see review

Jessica Chapman

Apr 12, 2020Jessica Chapman rated it really liked it

I would recommend this only selectively but I found this story of a Korean immigrant arriving the United States in the 1920s to be comforting during this unpredictable time in our country. The narrator has a critical eye - justifiably - but it never entirely overrides his wonder for his adopted country.

flagLike · comment · see review

Kevin Jagernauth

May 23, 2020Kevin Jagernauth rated it liked it · review of another edition

A unique perspective on the Korean immigrant experience in 1930s America, and an interesting window into the intersection of the religious and intellectual spheres of the time. Unfortunately, the philosophical digressions feel dated and often take the wind out of the episodic story's momentum. (less)

flagLike · comment · see review

Alex Kudera

Jun 27, 2021Alex Kudera rated it it was amazing · review of another edition

In the middle, I toyed with the possibility of four stars, but in the last fifty pages, I recognized that there was no reason for a deduction.

For the full Alexander Chee introduction and some of my favorite quotations from the book:

https://kudera.blogspot.com/search?q=... ...more

flagLike · comment · see review

Susan

May 26, 2021Susan rated it really liked it · review of another edition

A bit slow-moving for me, but the fresh perspective of an Asian new to our country was priceless.

flagLike · comment · see review

KC Grim

Oct 05, 2020KC Grim rated it it was ok

Shelves: books-for-classes

Not the sort of narrative structure I needed right now. Was a bit of a chore but interesting in some parts.

flagLike · comment · see review

Amelia

Dec 24, 2021Amelia rated it liked it · review of another edition

3.25

flagLike · comment · see review

Katy

Jun 12, 2021Katy rated it it was amazing

Long but worth it.

flagLike · see review

Eugenia Kim

May 28, 2010Eugenia Kim added it

Shelves: koreana-fiction

This literary autobiographical novel chronicles an immigrant’s experience of America in the 20s through the war years, in New York City. Connection is made through the young man's education, his camaraderie with other émigrés, the kindness of friends, and the exchange of Chinese classic poetry. First published in 1937 and edited by powerhouse star editor Max Perkins. A seminal work in Korean American literature. (less)

flagLike · comment · see review

Kat

Feb 15, 2014Kat rated it really liked it

It's not quite a four star for me, but not a three. Goodreads needs halves.

Interesting work, so much meditation on poetry and literature, and worth reading especially if interested in the exile/immigrant experience. (less)

flagLike · comment · see review

Like No One They’d Ever Seen

Ed Park

What if the finest, funniest, craziest, sanest, most cheerfully depressing Korean-American novel was also one of the first?

April 23, 2020 issue

Submit a letter:

Email us letters@nybooks.com

Reviewed:

East Goes West

by Younghill Kang, with a foreword by Alexander Chee and afterword by Sunyoung Lee

Penguin, 389 pp., $18.00 (paper)

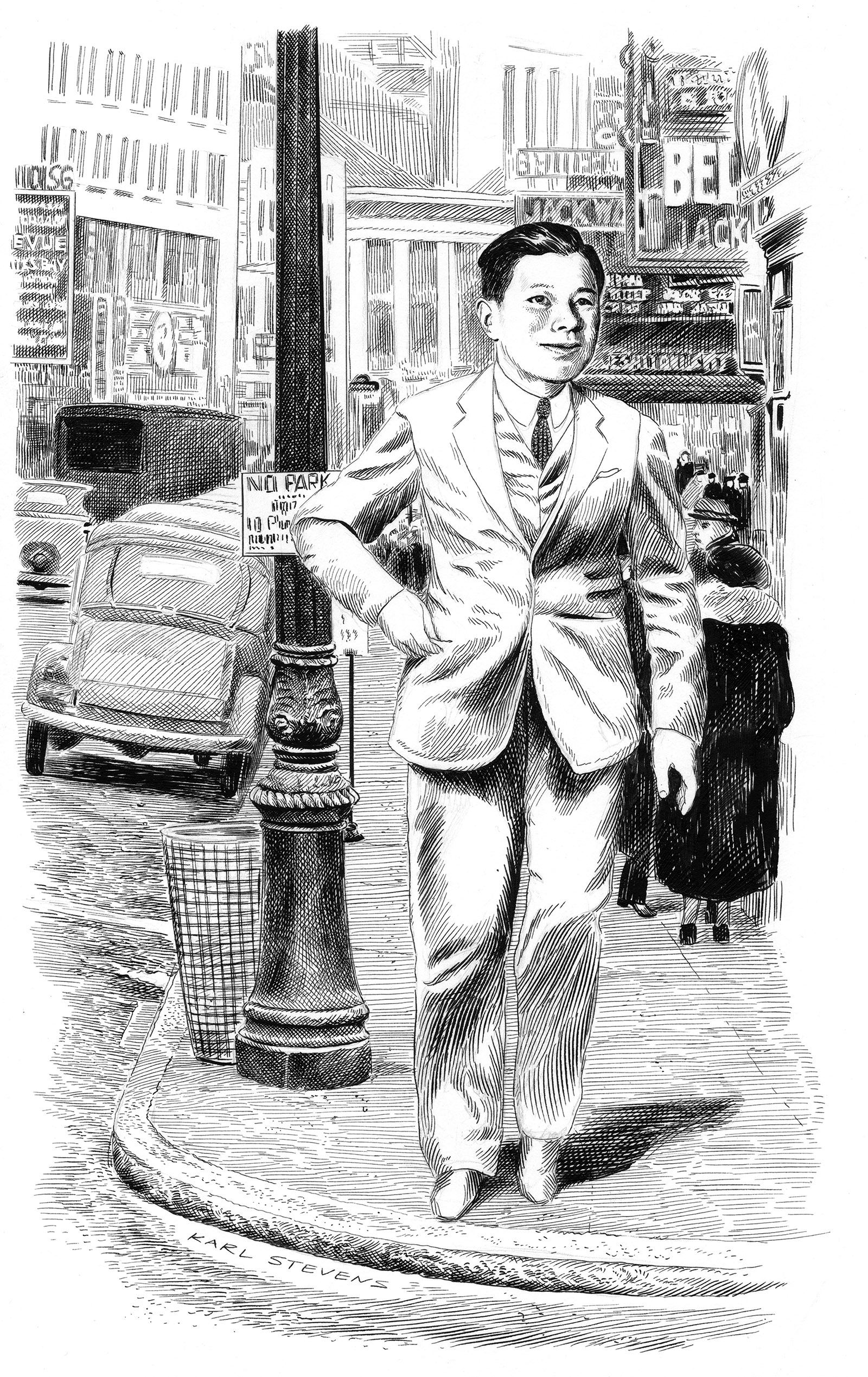

Younghill Kang; drawing by Karl Stevens

Younghill Kang; drawing by Karl StevensWhat if the finest, funniest, craziest, sanest, most cheerfully depressing Korean-American novel was also one of the first? To a modern reader, the most dated thing about Younghill Kang’s East Goes West, published by Scribner’s in 1937, is its tired title. (Either that or its subtitle, “The Making of an Oriental Yankee.”) Practically everything else about this brash modernist comic novel still feels electric.

East Goes West has a ghostly history: at times vaguely canonical, yet without discernible influence, it has been out of print for decades at a stretch, and surfaces every quarter-century or so as a sort of literary Brigadoon. (Last year’s Penguin Classics edition is its third major republication.) Kang’s debut, The Grass Roof (1931), captures the twilight of the Korean kingdom in the first two decades of the twentieth century, as Japan colonizes the peninsula. Its narrator, Chungpa Han, is a precocious child whose thirst for education takes him from his secluded home village to Seoul, three hundred miles away; into the heart of Japan; and finally to America, where East Goes West picks up on the pilgrim’s progress.

Though both novels were first published to great acclaim by Maxwell Perkins—the legendary editor of Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Thomas Wolfe—they stand as the alpha and omega of Kang’s fiction career: an explosion of talent, followed by thirty-five years of silence. His sensual, impudent voice and bold escape from his homeland (“I had seen the disintegration of one of the first nations of Earth”) provoked Rebecca West to exclaim, in a review of The Grass Roof, “What a man! What a writer!” Yet by the time of his death in 1972, Kang had faded from public recognition.

The fictional Chungpa Han’s itinerary and timeline generally tracks Kang’s. Born around 1903, he grew up in rural North Korea, stuffing himself with Korean and Chinese poetry. At age eleven, he trekked alone to Seoul, a journey of sixteen days, to further his education, then went to Japan the next year. Back in Korea by 1919, he participated in the March 1 Movement, a nationwide uprising against Japanese rule, for which he and thousands of others were jailed. (Among The Grass Roof’s virtues is a ground-level account of the event and its aftermath.) Following a thwarted attempt to leave Japanese-occupied Korea via Siberia, and a second spell in jail, he finally made it to the US three years before the Immigration Act of 1924 effectively outlawed most immigration from Korea and other East Asian countries until it was replaced in 1965.

His audience in the 1930s, then, was not the Korean diaspora, for the simple reason that there hardly was any. (Between 1903 and 1924, fewer than 10,000 Koreans had come to the US, most of them as laborers in Hawaii and California.) He wrote instead as the last of his breed, addressing those Americans with little sense of Korea’s existence, let alone its vexed status as a colony of Japan (1910–1945). He was a man without a country: an alien unable to obtain US citizenship due to immigration restrictions, and unwilling to return to a land that no longer existed.

He assimilated with a passion. He studied at various schools (obtaining a master’s in English education from Harvard) and married a Caucasian woman, a Wellesley graduate named Frances Keely (she was also an alien for a time: her US citizenship was revoked for marrying an Oriental). His deep knowledge of East Asian culture equipped him to be a writer for the Encyclopaedia Britannica and a curator for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1929 he taught literature at New York University, living in Greenwich Village. At NYU, Kang befriended fellow instructor Thomas Wolfe, on the verge of publishing Look Homeward, Angel. Wolfe changed Kang’s life by recommending him to Perkins, who brought out The Grass Roof—the only book that Wolfe ever reviewed.

By the time immigration restrictions loosened in the 1960s, Kang’s writing from the 1930s must have seemed remote to newer arrivals. The next significant novel in English by a Korean immigrant, Richard E. Kim’s The Martyred (1964), was its stylistic antithesis: a brooding, Camusian work set during the Korean War (1950–1953), in which Kim served as an infantry lieutenant.

Kang’s DNA is hard to locate in the varied work of the Korean-American novelists since. As a result, East Goes West’s tumbling prose and loose, picaresque structure feel amazingly “free and vigorous” (per Wolfe) today.

Early on, East Goes West appears to be a comedy of errors, perhaps laying the groundwork for a Horatio Alger story: youthful Chungpa Han arrives alone in New York City from Korea, via Japan and Canada, with two letters of introduction, four dollars, and the keen sense of life starting anew. (Chungpa notes that the Korean word for “boat” is the same as that for “womb.”) He extols Manhattan as “that magic city on rock yet ungrounded, nervous, flowing, million-hued,” crammed with “young, slim, stately things a thousand houses high,” a “great nature severed city [festooned] with diamonds of frozen electrical phenomena” that is destined to be “the vast mechanical incubator of me.” The description practically bursts into flames; here and elsewhere, Kang calls to mind no one so much as that later Wolfean disciple, Jack Kerouac.

Advertisement

The very sight of New York stirs his soul because—more than Paris, London, or “age-buried Rome”—it’s the apotheosis of the Machine Age, and thus the opposite of his homeland, whose resistance to change spelled its doom. Whereas in The Grass Roof Chungpa depicts his native country as a wonderland of faithful canines and revered crazy poets, easily crushed by a more modernized Japan, on the second page of East Goes West, he describes Korea in darkly apocalyptic terms, a catastrophe out of science fiction:

It was my destiny to see the disjointing of a world. Upon my planet in lost time, the heyday of life passed by. Gently at first. Its attraction of gravity, the grip on its creatures maintained through its fervid bowels, its harmonious motion weakened. Then the air grew thin, cooler and cooler. At last, what had been good breathing to the old was only strangling pandemonium to the newer generations.

Fleeing “the death of an ancient planet,” our hero lands in an America so strange it might as well be Mars. He announces that the book which follows—East Goes West—will be “the record of my early search” for roots in this foreign place.

Reaching New York, Chungpa Han is in high spirits. For his first night, he splurges on a mid-tier hotel. The elevator gives him a “funny cool ziffy feeling,” and the bathroom is a marvel, unlike anything in Korea. The hotel mirror is also a novelty; in his old life, a mirror was generally a covered thing “about the size of a watch.” Seeing his old-world face in a brand-new country brings on something close to hypnosis:

I have read that Koreans are a mysterious race, from the anthropologist’s viewpoint. Mixtures of several blood streams must have taken place prehistorically. Many Koreans have brown hair, not black—mine was black, so black as to have a blackberry’s shine. Many have naturally wavy hair. Mine was quite straight, as straight as pine-needles. Koreans, especially women and young men, are often ivory and rose. My face, after the sun of the long Pacific voyage, suggested copper and brass. My undertones of the skin, too, mouth and cheek, were not at all rosy, but more plum. I was a brunette Korean. Koreans are more animated and hot-tempered than the Chinese, more robust and solid than the Japanese, and I showed these racial traits as well…. My limbs retained a look of extreme plasticity, as in a growing boy, or in a Gauguin painting, but with many Koreans, even grown up, they still do.

For Chungpa to establish his alien self at the outset of this story, describing it as a specifically Korean body, distinct from the somewhat better-known Chinese or Japanese ones (and even from those of other Koreans), is a radical move. It suggests that American readers need to know exactly how he looks, or they’ll fail to understand his story. There’s also a quality of self-revelation, as though he needed to go halfway around the world to see himself fully, in the privacy of a New York hotel room. Rather than dwelling on the melancholy of anatomy, he notes his “extreme plasticity,” to show that he’s ready for America to transform him.

On his second day in New York, Chungpa Han gets a haircut, not grasping that shampoo, shave, and other services cost extra. He leaves the barbershop with a dime to his name. He is counting on imminent employment, but his two letters prove useless. A nickel gets him a space on a basement floor, in what he likens to “a crypt of roughly piled bodies.” In just forty-eight hours, he’s gone from Whitmanesque paeans to a premonition of death. The feeling of liberation from his old life has been replaced by the need to adapt. Constant reinvention, he learns, is in the American grain.

So too does the book reinvent itself. A rags-to-riches arc dissolves into a journey through eastern North America. Already steeped in the English poetic tradition, Chungpa pursues his “avid desire for Western knowledge” while he works a succession of jobs. Educational opportunities, finances, and pure wanderlust compel him to roam, and the scene shifts from New York (a humiliating stint as a houseboy, assistant to a tea importer, waiter at a Chinese restaurant) to Nova Scotia and other spots in Canada (college, box factory, farming), then Boston (pen salesman, more school, book salesman, busboy), Philadelphia (department store), and myriad unnamed points across the country, eventually returning to Manhattan.

Advertisement

Even as a boy, Chungpa wandered, as chronicled in The Grass Roof. At the age of eleven, determined to be a “big man,” he “wanted to go to Seoul one day and get this country straightened out.” (“I will drive out all those Japanese.”) In Seoul at last, after a grueling solo journey, he writes home: “I am not going to send any more letters until I get more education. There are no good schools in Seoul.” The grit offsets his grating precocity: seemingly from birth, Chungpa is fluent in classical Chinese poetry, a hallmark of the Korean literati. He quotes it at the drop of a hat, and revels in his destiny as a future pak-sa, a gentleman scholar.

The looming destruction of his country by its colonizers ultimately renders Chungpa heroic, a young man whose resourcefulness outshines his arrogance. What he held as his birthright gets dashed against political reality:

For the first time in my life I could not make up my mind. After graduation, what? Get a job. Yes, but in Korea I should have to be a subordinate of a Japanese, always I would get one-tenth of that which a Japanese with the same degree would get, I could never become a pak-sa for there were no more pak-sas and a Korean premier did not exist…. If I went back to Korea, and returned to become a villager for always, was that any fun? Why should I keep on to manufacture babies for which there could be no future? I saw what Japan’s policy toward Korea would be: all who could not be assimilated would be slaughtered…and driven away.

He finally secures passage (and eludes Japanese officials) by accompanying a widowed American missionary and his four children, impersonating an “ignorant coolie boy.”

As a narrator, however, Chungpa is more charismatic in East Goes West. When it dawns on him that America is like nothing he could have imagined, the comedy kicks in. Reviewers took The Grass Roof for straight autobiography, and East Goes West saw the same fate. Kang’s second book, however, shows him to be a skilled novelist rather than a simple recorder of his own life. Kang turns down the volume on his narrator whenever Chungpa encounters someone who captures his curiosity or affection. The novel overflows with memorable motormouths, busybodies, sad sacks, and dreamers, both foreign and domestic, white and black and “Oriental.” (“I was outside the two sharp worlds of color in the American environment,” Chungpa notes, allowing him to observe his new countrymen with an unbiased eye.)

The first bit of fun arrives in the form of George Jum, a fellow expat with whom Chungpa has corresponded. Originally a diplomat, George now works as a cook and leads a happy bachelor life on West 72nd Street, where he invites his countryman to stay. His debonair style and instant friendliness win over Chungpa (and the reader—you can’t help but smile when his name pops up). Like P.G. Wodehouse’s Bingo Little, he’s in love with being in love, rhapsodizing on the nature of American romance. While George irons pants to prepare for his day, Chungpa asks whether he’d ever get hitched. “I am thinking of love, not of marriage,” George begins, then expounds uninterrupted for a page, gleefully mixing truisms (“Anything that law commands in the form of thou shalt not, that thing man wants more”) with boneheaded logic: “But then civilization is a good thing. We enjoy motor cars and bathtubs. And who would not enjoy having more than one wife?”

George Jum functions as the happy opposite of the older, highly cultured To Wan Kim, some sixteen years removed from his homeland, who can neither find peace in the West nor consider himself a Korean: “I have been away so long I do not feel one any longer,” he confesses. Chungpa glimpses the refined and rootless gentleman during his first stay in New York, though they don’t introduce themselves until a few years later, recognizing each other at a Chinatown restaurant.

The doomed To Wan falls in love with Helen Hancock, a Boston blue-blood whose older cousin fancies himself a connoisseur of all things Asian, yet whose family sternly forbids their romance. George Jum and To Wan Kim loop through Chungpa’s life at irregular intervals, suggesting possible paths for the educated Korean immigrant—or the necessity of creating your own.

To Wan has a tragic trajectory, but George shines as the first of dozens of amusing secondary portraits. Others include his fellow Korean Doctor Ok, who has racked up four degrees and counting (perhaps a jab at Syngman Rhee, future first president of South Korea, who rather incredibly obtained, between 1907 and 1910, a BA from George Washington, an MA from Harvard, and a Ph.D. from Princeton); the irrepressible D.J. Lively, who runs a pyramid scheme selling a self-help tome called Universal Education; and Senator Kirby, who picks up a hitchhiking Chungpa and heartily tells him to call himself an American—and also that Marlowe wrote Shakespeare’s plays.

But there’s another strain of humor here, a sort of deadpan ramble, anticipating the later comic novels of Charles Portis, which draw laughs by cutting off a seemingly limitless series of observations at an unexpected point. In this vein, Kang produces witty portraits of Chungpa’s fellow foreign college students, such as an Italian roommate who somehow removes and dons his necktie only when no one’s looking, and the homesick Peking University graduate Eugene Chung, whose sober hobby is his new typewriter:

When he was not writing long letters to his wife in Chinese, he was practising [sic] with his typewriter the touch method, spending hours and hours on just his name…. His only regret was, he could not combine his two interests, write his wife and at the same time use that machine. This he could not do because she knew no English.

Kang is even funnier when observing whites. During his Canadian sojourn, Chungpa is unaccountably fascinated by a mildly unusual ménage:

I remember the Stratford [Ontario] barber who boarded at Mrs. Moody’s all the time…. This barber looked like a farmer and not a barber, and in fact I think he had newly become a barber, not liking the dirt of farm life. It was his ambition to get down to Boston. He was engaged to a girl who ran the only beauty shop in Stratford and who was always unusually dressed. Her clothes, though they were made at home by her dressmaker sister, seemed copies of Parisian styles. One time she would appear in a dress with long sleeves—extraordinarily long, I mean, down to the knees. Or she would wear an enormously wide flopping straw hat with streamers. Besides, she was always exceptionally decorated underneath, whether as an advertisement of her shop or just to take advantage of it, I can’t say…. She, too, no doubt, was eager to get down to Boston. They never managed it. Several years later, as I drifted north once more, I saw them both in Stratford, married and settled down…. They had a fat boy-baby now, whose ambition ultimately perhaps will be to go to Boston.

The thwarted, multigenerational ambition to make it to Boston is the chief joke here, but it’s kept alive by little virtuosic touches: the barber’s farming past, the shopkeeper’s outré clothes, the interjections (“I mean,” “I can’t say”) that remind you that the man watching the comedy play out—Chungpa Han—must look like no one else they’d ever seen. “I was inexorably unfamiliar,” he reflects.

The novelist and memoirist Alexander Chee’s rousing introduction to the new Penguin Classics edition of East Goes West argues strongly for its relevance today. Chee says that “Kang wrote East Goes West as a call to action, a call for [America] to live up to the dream it has of itself,” and he rightly touches on how Kang illuminates a whole shadow community of marginalized immigrants—most of them Asian, all in a sort of historical limbo. Some thrive, most stagnate, a few go mad with homesickness. “Perkins tried to get Kang to write a happier book,” Chee points out, “but Kang had deliberately imagined a less successful and happy life for Han than the one he himself had lived, in part to dramatize the plight of those less fortunate than he was.”

But I’m more cynical than Chee about the book’s utility as a rallying cry. Its value is in the heady mix of high and low, the antic yet clear-eyed take on race relations, the parade of tragic and comic bit players, and above all, the unleashed chattering of Chungpa’s distinctive voice. Underlying the richness and humor, there’s a deep pessimism about making it in America, for anyone not white and male. In Boston, a college-educated black friend, Wagstaff, works as an elevator man, and “expected all his life to be an elevator man.” Chungpa’s white male coworkers at the Boshnack Brothers department store in Philadelphia spread rumors that their female counterparts, who earned $12 a week, “made a side-living by prostitution, since it was impossible to live on that in a big city.” (In the company’s men’s club, they throw around the n-word with sickening impunity.)

As for Chungpa, his jobs have all been menial; how is his American existence any better than life under the Japanese back home, who “wanted all honored men in Korea to become coolies”? “I couldn’t make him understand about Korea,” Chungpa says of a bum; by the end of the book, white America by and large still doesn’t know what to make of him.

Catching the flu in Boston, Chungpa has a vision of despair. “Nobody would know the moment when I died and nobody would care,” he moans. “Many Oriental students had died like this on foreign soil.” A fellow expat’s death merits a brief mention in the paper on “the suicide of a friendless ‘Japanese’ on Bleecker Street.” Even in death, Koreans remain indistinct.

Chee and I could both be right. East Goes West is bookended by dreams, the first an enthralling fantasy of New York, the last a soul-killing nightmare: a final verdict might depend on how you interpret the latter. At some point in his American life, a slumbering Chungpa is vouchsafed a glimpse of long-lost boyhood friends (previously unmentioned in East Goes West, but present in The Grass Roof) before plunging into “a dark and cryptlike cellar” somewhere “under the pavements of a vast city”—flashing back to his destitute second night in New York. A “red-faced” mob shoves its torches “crackling, through the gratings” of the cell that he shares with “some frightened-looking Negroes.”

Chungpa’s own interpretation of this incendiary scene feels tacked on, homiletic. To be killed by fire in a dream “augurs good fortune,” according to “Oriental interpretation.” He gives it a Buddhist spin (death symbolizes “growth and rebirth and a happier reincarnation”) that feels peculiarly unconvincing—the only line in the book I don’t believe he means. The book ends abruptly, as though the chatty Chungpa is still too rattled by what he’s conjured.

After World War II, in that heartbreakingly brief span of time between the liberation of Korea from Japan and the outbreak of the Korean War, Kang returned to his homeland for two years, at the invitation of the US Army Military Government in Korea (going by the mystical acronym USAMGIK). He had been away too long; his presence didn’t make sense to Koreans or to himself. “Thirty million frustrated, confused, and humiliated Koreans are trying to become a nation,” he complained to Perkins. “We are getting nowhere.” In Robert T. Oliver’s hagiographic Syngman Rhee: The Man Behind the Myth (1954), Kang is depicted as ineffective and apolitical, telling reporters: “I don’t like or trust Dr. Rhee…I’m a writer, an artist.” According to Oliver (who was, in essence, Rhee’s stateside publicist during this time), Kang’s irrelevance to Koreans led US officials to shunt him to a back room.

In 1948 Younghill Kang returned to the US, and during the Korean War, according to Sunyoung Lee’s chronology, “Kang’s restless anxiety [over the war] makes it difficult for him to reacculturate to American life.” In his 1954 application for a Guggenheim fellowship, he writes in anguish:

It is natural for me to love America and fight for her, it is natural for me to love Korea…. I know why the UN or [President] Truman has done what has been done [i.e., entered the war upon Communist North Korea’s invasion of the South]. But I also know we have spent millions and lives and created enemies in Korea…. What is it they fight? Communism? democracy?… To the average Korean what do they mean? The typical Korean is a hunted uneducated farmer. One thing makes him go mad, that 38th Parallel, separating parent from child, husband from wife…. Whichever force won this war from without shall lose it politically. The operation was a success, but the patient died—it’s that kind of success.

The great powers—the US on one side, China and the Soviet Union on the other—were spelling out the terms of Korea’s doom, just as surely as Japan had earlier in the century.

With Frances, he translated Meditations of the Lover, poems by the Korean poet and Buddhist monk Han Yong-un (1879–1944); it was rejected by Scribner’s. (Perhaps Han’s surname inspired Chungpa’s.) Save for a 1954 translation of the Japanese play Anatahan (Hermitage House), Kang never published another book in America. Through the 1950s, he wrote for various encyclopedias, mostly entries about China. When he wasn’t teaching or working on farms on Long Island, he drove around the country delivering lectures on topics like “The Democratic Opportunity in Asia.”

By chance, two strange sheets of paper fell out of my used copy of The Grass Roof (a 1966 printing of the 1959 Follett reissue), and they afford a rare peek at the nature of Kang’s later life, long after the dissipation of his fame. The book was inscribed by Kang to a reader in 1970, two years before Kang’s death. The sheets, a pair of advertisements for himself, were almost certainly made by Kang; though undated, they might be the last thing he wrote for some imagined general reader.

Sheet one, which I take as being of earlier origin, is the more professional looking. It has a portrait of Kang in coat and tie, seated at a desk, downcast eyes studying an open book. Plaudits include what appears to be a long blurb from Pearl S. Buck. But only the first few words (“one of the most brilliant minds of the East”) are hers; the rest is a Who’s Who–like list of accomplishments. The reverse displays nine raves for his novels. The layout is dense but orderly, and the spotlight is firmly on his rich literary legacy.

The second sheet appears to be from a later date. Ostensibly it touts his public-speaking bona fides. One side bears typewritten extracts from his speeches, plus his home address in Huntington, Long Island. The other side, though, looks like the snapshot of a meltdown: a blizzard of text, in a dozen conflicting typefaces and angles, comprising shards of testimonials and invitations (“LUNCHEON IN ALEXANDER DINING HALL”). It’s hard to know what’s being offered. The word “Vietnam” ominously appears, unattached; then the eye makes out the tiny words “Or Negotiation?” A chunk of Rebecca West’s age-old review drifts through, as does a Grass Roof review, but it’s clear he’s long since abandoned his life as a novelist.

It’s a shocking composition. The ennobling lecture extracts on the obverse (“Great books are still the greatest weapons in fighting, and the only lasting psychological propaganda”) have been replaced by noise and chaos. No novelist’s permanence is assured, but given Younghill Kang’s primacy as the first Korean-American novelist, this feels like a higher order of defeat, as though the country that he so endeavored to be part of had turned its back on him. To gaze upon this frenzied collage is to wonder if some part of his soul had taken up residence in the cell of his youthful alter-ego’s hair-raising dream—a form of PTSD, from a war he wasn’t actually in but that he felt in his bones.

The Penguin edition of East Goes West reminds us of how excellent he really was. Written in the 1930s, set in the 1920s, the book is thrillingly timeless. Kang’s obscurity cannot negate his heroic path to becoming a great American novelist—casting off one tongue to master another. In a 2008 essay in Guernica on Korean-American fiction, Chee aptly calls East Goes West a “Nabakovian [sic] tour de force.” Though Nabokov expressed no interest in “the entire Orient,” he and Kang—poets in their youth—have much in common. Both lived from the turn of the century to the 1970s, and in their late teens fled homelands in upheaval. Both found fame in the US, as stylistically daring novelists for whom English was a second language—in Kang’s case, third or even fourth, as he wrote poetry in Chinese and studied in Japan.

Given that The Grass Roof and East Goes West precede Nabokov’s American debut, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight (1940), by nine and three years, respectively, it’s worth asking: Was Kang the first exophonic American to execute such highwire English prose? Regardless of whether he’s the right answer to this parlor game, Kang wrote a vast, unruly masterpiece that is our earliest portrait of the artist as a young Korean-American, at a time when hardly any Americans had heard of, let alone seen, a Korean. His insistence on the value of his own identity to a modern world that had essentially condoned the foreign takeover of a sovereign nation brings to mind West’s tribute: What a writer—what a man.

This Issue

April 23, 2020

Jason Farago

Jason FaragoResistance Is FutileDavid Quammen

The Brilliant PlodderAll Contents

Subscribe to our Newsletters

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

More by Ed Park

A Good Story to Tell

October 30, 2021

A Poet’s-Eye View

Yi Sang, Korean literature’s perpetual enfant terrible, was not only a cutting-edge writer but a working architect, and his oeuvre teems with dark rooms, mirror worlds, and other uncanny spaces.

October 21, 2021 issue

Ed Park

Ed Park is the author of the novel Personal Days. He wrote the essay for the Criterion Collection edition of Bong Joon Ho’s Memories of Murder. (October 2021)

===

동양선비 서양에 가시다

강용흘 (지은이),유영 (옮긴이)종합출판범우2021-06-20

450쪽

책소개

3.1운동 직후 미국으로 건너가 작품 활동을 한 강용흘의 장편소설. 강용흘은 1919년 3.1운동 직후 미국으로 건너가 수십 년 동안 해외에서의 작품 활동으로 미국 및 유럽 등지에 명성을 떨친 작가 중 한 사람이다. 그는 우리 민족사상 가장 위대했던 외세에 대한 항쟁이랄 수 있는 3.1운동의 수난과 좌절을 다루어 일제하 우리 국민들이 끝까지 민족정기를 지키는 시대상황을 작품화한 《초당》으로 세계에 우리의 위상을 높였다. 이를 다시 나라 밖으로 연장하며 그 정신을 계속 떨치었던 그의 작품의 속편이라 할 《동양선비 서양에 가시다》를 출간함으로써 문학사적 위치를 확고히 하였다.

목차

▨ 이 책을 읽는 분에게 · 5

제1편 9

제2편 109

제3편 331

작품론 439

연보 449

저자 및 역자소개

강용흘 (지은이)

저자파일

신간알리미 신청

재미교포 소설가. 함경남도 홍원 출생.

3.1운동 후 18세 때 중국과 일본을 거쳐 도미(渡美)하여 보스턴 대학에서 의학을, 하버드 대학에서 영미문학을 전공함. 이어 《대영백과사전》의 편집위원으로 근무하면서 창작에 전념했다. 1931년 한일합방과 3.1운동을 배경으로 한 자전적인 첫 영문 장편소설 〈초당〉을 발표하였다. 그 후 로마 대학뮌헨 대학파리 대학 등에서 연구했으며, 뉴욕 대학 등에서 동양문화와 비교문학을 강의하였다.

작품 〈초당〉으로 ‘구겐하임 상’과 ‘북 오브 더 센추리 상’을 수상하였고, 장서 5000권을 고려대학교에 기증하였다.

작품으로는 소설 〈행복한 숲〉〈동양선비 서양에 가시다〉, 희곡 〈왕실에서의 살인〉등이 있으며, 역서로는 〈동양 시집〉한용운의 〈님의 침묵〉 등이 있다. 접기

최근작 : <동양선비 서양에 가시다> … 총 2종 (모두보기)

유영 (옮긴이)

저자파일

신간알리미 신청

경기도 용인 출생.

서울대학교 문리대 영문학과 졸업. 문학박사.

연세대 명예교수.

1944년 치안유지법 위반으로 옥고중 해방이 됨.

국민훈장 동백장 받음.

저서로는 《일월》,《인간 별곡》(시집), 《나의 대학의 오솔길》

《산문집》,《밀턴 문학의 심층구조 연구》 등이 있으며,

역서로는 《실낙원 복낙원》,《아들과 연인》,《젊은 예술가의 초상화》

《타고르 전집(6권)》,《일리아스》,《오디세이아》,

《동양선비 서양에 가시다》 등이 있음.

최근작 : <더버빌 가의 테스>,<호박꽃 타령>,<타골의 문학:그 신화와 신비의 미학> … 총 34종 (모두보기)

출판사 제공

책소개

3.1운동 직후 미국으로 건너가 작품 활동을 한 강용흘 장편소설

강용흘은 1919년 3.1운동 직후 미국으로 건너가 수십 년 동안 해외에서의 작품 활동으로 미국 및 유럽 등지에 명성을 떨친 작가 중 한 사람이다.

그는 우리 민족사상 가장 위대했던 외세에 대한 항쟁이랄 수 있는 3.1운동의 수난과 좌절을 다루어 일제하 우리 국민들이 끝까지 민족정기를 지키는 시대상황을 작품화한 《초당》으로 세계에 우리의 위상을 높였다. 이를 다시 나라 밖으로 연장하며 그 정신을 계속 떨치었던 그의 작품의 속편이라 할 《동양선비 서양에 가시다》를 출간함으로써 문학사적 위치를 확고히 하였다.

작품 해설 : 세계로 비상한 민족정기의 날개

유 영(연세대 명예교수/문학박사)

| 이 책을 읽는 분에게 |

30년대에 밀항을 하다시피 하여 단돈 4달러로 미국으로 건너간 동양의 작은 나라 한국의 한 젊은이가 무수한 격랑을 넘어 악전고투 끝에 남긴 작품은 미국은 물론 전세계를 놀라게 했다. 강용흘은 여러 개의 상을 휩쓸었던 《초당》의 후편격인 《동양선비 서양에 가시다》로 또다시 세계를 놀라게 했다.

이 작품은 《초당》의 명성이 세계에 떨친 이후 창작기금을 받고 유럽으로 가서 집필에 충분한 편의를 제공받으며 이루어진 것이다. 첫 번째 책처럼 부족한 상황에서 이루어진 것이 아니라 충분한 마음의 여유와 재정적인 뒷받침으로 이루어진 만큼 작품의 질에 있어서도 더욱 두드러진다.

말하자면 《초당》이 국내에서 있었던 3·1 운동의 진행 상황을 형상화한 것이라면 이 작품은 이 운동의 좌절을 딛고 해외로 나가 세계를 상대로 3·1 정신의 뿌리와 민족의 기개를 알리고 또 실천하려는 정신 운동의 단면이라고 볼 수 있다.

그는 온갖 고난과 애로를 넘어 끝까지 민족의 긍지를 지키며 한국의 얼, 배달민족의 의기, 동방예의지국의 비전을 살리며 세계 지성의 정상까지 이른다. 우리 선비의 이 끈기와 인내와 극기 정신에 누구나가 놀라지 않을 수 없을 것이다. 그는 더욱이 거의 굶다시피 하고 하늘을 지붕으로 자기도 하면서도 자기 삶의 목표만을 향해 전진한다.

이 거룩한 투쟁사는 참으로 손에 땀을 쥐게 하며 가슴 뛰게 한다.

그런가 하면 유머와 해학을 잊지 않고 진행이 항상 희로애락의 인생 행로의 다반사를 흥미 있게 엮어가고 있다.

또 많은 외국인을 만나서 교류가 이루어지는데 이들의 국민성과 습성 따위를 잘 수용하고 화합을 이룸으로써, 그 뛰어난 인품 또한 감격의 큰 흐름을 이루고 있다.

따라서 이들과의 교류에서 남긴 수많은 에피소드와 국제적인 인종문제에 대한 새로운 접근이 작품의 맛을 더해주고 있다.

다시 만나는 동포들과의 교류, 동포들의 고난과 협력 관계, 고국과의 연관 문제에서도 3·1 운동에서 겪었던 피나는 체험과 의식을 이어가며 인생 행로를 개척하는 것에 주목할 수 있다. 더욱이 언제나 조국에 대한 애국심과 고향을 그리는 향수, 자신의 뿌리와 자신의 핏줄에 대한 따뜻함과 거룩함을 적어나가는 주인공은 오로지 한국의 선비로서 참다운 인격을 닦는 데 매진하고 있다. 따라서 만나는 동포들이 이국 땅에서 겪는 무수한 고난, 좌절, 실의에도 항상 재기하는 모습을 부각하는 데 소홀하지 않다는 인상을 준다.