Thursday, January 27, 2022

Chapter 2 The Study of Irregular Migration

Lee, Seunghun Towards a Systemic Theory of Irregular Migration | SpringerLink

===

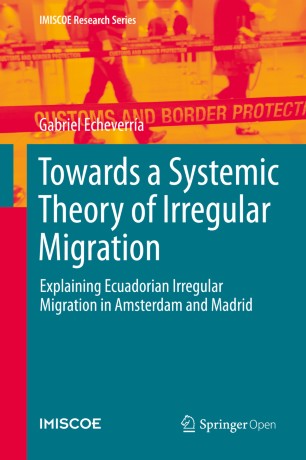

Towards a Systemic Theory of Irregular Migration

Explaining Ecuadorian Irregular Migration in Amsterdam and Madrid

Authors

(view affiliations)

Gabriel Echeverría

This open access book provides new comparative, empirical, qualitative material on irregular migration

Nests the understanding of irregular migration within a more general sociological interpretation of contemporary society

Gives an alternative theoretical framework and critical review of irregular migration

Open Access Book

2Citations

7Mentions

25kDownloads

Part of the IMISCOE Research Series book series (IMIS)

Download book PDF

Download book EPUB

Buying options

Softcover BookEUR 49.99Price excludes VAT (Australia)

ISBN: 978-3-030-40905-0

Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

Exclusive offer for individuals only

Free shipping worldwide

Shipping restrictions may apply, check to see if you are impacted.

Tax calculation will be finalised during checkoutBuy Softcover Book

Hardcover BookEUR 49.99

Learn about institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (8 chapters)

About this book

Search within book

Front Matter

Pages i-xii

Introduction

Gabriel Echeverría

Pages 1-7 Open Access

Theoretical Study

Front Matter

Pages 9-9

The Study of Irregular Migration

Gabriel Echeverría

Pages 11-39 Open Access

Irregular Migration Theories

Gabriel Echeverría

Pages 41-94 Open Access

Understanding Irregular Migration Through a Social Systems Perspective

Gabriel Echeverría

Pages 95-125 Open Access

Empirical Study

Front Matter

Pages 127-127

Methodological Note

Gabriel Echeverría

Pages 129-138 Open Access

Ecuadorian Migration in Amsterdam and Madrid: The Structural Contexts

Gabriel Echeverría

Pages 139-181 Open Access

Ecuadorian Irregular Migrants in Amsterdam and Madrid: The Lived Experience

Gabriel Echeverría

Pages 183-226 Open Access

Conclusion

Front Matter

Pages 227-227

Steps Towards a Systemic Theory of Irregular Migration

Gabriel Echeverría

Pages 229-246 Open Access

===

PAPERS AND PRESENTATIONS

Publication (up to 2019)

Presentations (up to 2019)

Recent Publication by members

Fukuda, Masaki, Kosei Kimura, Reed Blaylock, Seunghun J. Lee (2022, to appear) Scope of Beatrhyming: Segments or Words. In Proceedings of AJL6.

Lai, Audrey and Seunghun J. Lee (2022, to appear) Maximizing Lexical Contrast in Burmese Tone: Evidence from F0 and OQ. In Proceedings of AJL6.

Griffen, Laura and Seunghun J. Lee (2022, to appear) Morphohonological realization in back vowels in Jeolla and Seoul Korean. In Proceedings of AJL6.

Abe, Yuko, Daisuke Shinagawa and Seunghun J. Lee (2022, to appear) Notes on NC clusters in class 9/10 nouns of six South African Bantu languages. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics. (peer-reviewed)

Hlungwani, Crous M. and Seunghun J. Lee (2022, to appear) Object markers block locative inversion in Xitsonga. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics. (peer-reviewed)

Riedel, Kristina and Seunghun J. Lee (2022, to appear) Notes on geminates in Sesotho, Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics. (peer-reviewed)

Sumlut, Roi, Ryota Sakurai, Seunghun J. Lee (2022, accepted) Higher Education Institutions’ Responses to the COVID-19 Outbreak: An Analysis of Crisis Communication Patterns in 12 Universities’ Public Announcements. Educational Studies 64 (peer-reviewed)

Arii, Tomoe, Seunghun J. Lee, Tomoyuki Yoshida, Jee Eun Sung (2022, accepted) Effects of age, word order, and sentence types on Japanese sentence comprehension: A replication study of Sung et al. (2017) and Sung (2015) on Korean. Educational Studies 64 (peer-reviewed)

Ibara, Yuri; MUTO, Hikaru; FUKUDA, Masaki; SUZUKI, Michinori; OHO, Atsushi; YOSHIDA, Tomoyuki; LEE, Seunghun J. (2022, in print) Remote data collection from younger and elder population using E-Prime and Superlab. Educational Studies 64.

Lee, Seunghun J. & Machi Niiya (2021) Migrant oriented Japanese language programs in Tokyo: A qualitative study about language policy and language learners. Migration and Language Education 2(1): 17-33. https://doi.org/10.29140/mle.v2n1.489 [LINK] (peer-reviewed)

Asami, S., Deng, Y., Sakurai, R., Sumlut, R. S., Suzuki, M., Wang, Q., & Lee, S. J. (2021). Annotated bibliography: L2 pronunciation research. International Christian University Institute for Educational Research and Service Technical Report, 2021-1. [LINK]

Lee, Seunghun J. & Kristina Riedel (2021) Pre-nominal DP modifiers and penultimate lengthening in Xitsonga. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics 62 "Crossing boundaries: A festschrift for Laura Downing": 107-134 [LINK] (peer-reviewed)

Lee, Seunghun J., Cédric Patin & Kristina Riedel (eds.) (2021) Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics 62: Crossing boundaries: A festschrift for Laura Downing.

Lee, Seunghun J. and Elisabeth Selkirk (2022, in print) A modular theory of relation between syntactic and phonological constituency. Oxford University Press. (peer-reviewed)

Lee, Seunghun J. (2022, in print) Constituent structure and sentence phonology of Korean. In. S. Cho and J. Whitman (eds.) The Cambridge Handbook of Korean Language and Linguistics. Cambridge University Press. (peer-reviewed)

Jung, Insung, Sawa Omori, Walter P. Dawson, Tomiko Yamaguchi, Seunghun J. Lee (2021) Faculty as Reflective Practitioners in Emergency Online Teaching: An Autoethnography, International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 18, Article number: 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00261-2 (peer-reviewed)

Lee, Seunghun J. (2021) Aspects of Xitsonga tone. In Kaji, Shigeki (ed.) Afurikashogo no Seichoo·Akusento (Tone and Accent in African Languages) [アフリカ諸語の声調・アクセント]. The Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. pp. 303-322. http://repository.tufs.ac.jp/handle/10108/99925

Crous M. Hlungwani, Seunghun J. Lee and Vicent Maswanganyi (2021) Xitsonga (S53). In: Seunghun J. Lee, Yuko Abe, and Daisuke Shinagawa (eds.) Descriptive materials of morphosyntactic microvariation in Bantu vol. 2: A microparametric survey of morphosyntactic microvariation in Southern Bantu languages Tokyo: ILCAA. pp. 135-191. (doi: 10.15026/99965) (peer-reviewed)

Netshisaulu, N. C., Salphina Mbedzi and Seunghun J. Lee (2021) Tshivenda (S21). In: Seunghun J. Lee, Yuko Abe, and Daisuke Shinagawa (eds.) Descriptive materials of morphosyntactic microvariation in Bantu vol. 2: A microparametric survey of morphosyntactic microvariation in Southern Bantu languages Tokyo: ILCAA. pp. 77-133. (doi: 10.15026/99964) (peer-reviewed)

Lee, Seunghun J., Daehan Won and Shigeto Kawahara (2021) COVID-19 Myth Busters in World Languages: A Case for Broader Impacts of Linguistic Research during the COVID-19 Crisis. Reports of the Keio Institute of Cultural and Linguistic Studies 52: 1-11. [LINK] https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/40022522489/

Lee, Seunghun J. and Tekonnang Timee (2021) A preliminary study on the intonation of Kiribati interrogatives. Reports of the Keio Institute of Cultural and Linguistic Studies 52, 121-132. [LINK] https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/40022521752/

Lee, Seunghun J. (2021) Phonetics of geminate nasals in Kiribati. Educational Studies 63: 57-67. http://doi.org/10.34577/00004791. (peer-reviewed)

Lee, Seunghun J. (2021) Engaging students in online classes using Slack. Center for Teaching and Learning, International Christian University. FD Newsletters 25(2): 10-12.

Kunzang Namgyal, Seunghun J. Lee, George van Driem, Shigeto Kawahara (2020) A phonetic analysis of Drenjongke. Indian Linguistics 81(1-2): 1-4. (peer-reviewed)

Sumlut, R. S., Sakurai, R., & Lee, S. J. (2020). COVID-19 initial responses communication system in twelve universities. International Christian University Institute for Educational Research and Service Technical Report, 2020-1. [LINK]

Sakurai, R., Sumlut, R. S., & Lee, S. J. (2020). COVID-19 communication system after four months in twelve universities. International Christian University Institute for Educational Research and Service Technical Report, 2020-2. [LINK]

Kawahara, Shigeto and Seunghun J. Lee (2020) Keio-ICU LINC 2020: Abstract booklet. lingbuzz/005641 [LINK]

Abe, Yuko, Seunghun J. Lee, and Daisuke Shinagawa (2020) A Morphosyntactic Survey of Microvariation of Southern Bantu languages: A pilot case of collaborative linguistic research in African contexts. Korea Association of African Studies (KAAS) Conference on the Second Half of 2020. December 4, 2020. pp. 29-42.

Lee, Seunghun J. & Crous Hlungwani (2020) Effects of morphology in the nativisation of loanwords: The borrowing of /s/ in Xitsonga. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus, Vol. 60, 71-90 (https://doi.org/10.5842/60-0-797) (peer-reviewed)

Lee, Seunghun J. & William G. Bennett (2020) Foreword. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus, Vol. 60, i-ii (doi: 10.5842/60-0-869)

Teno, Yuri & Seunghun J. Lee (2020) Identifying Prosodic Features in Heritage Learners of Japanese: A Study based on OPI Interviews. Studies in Foreign Language Education 34(2): 221-246. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16933/sfle.2020.34.2.221) (peer-reviewed)

Lee, Seunghun J. & Tekonnang Timee (2020) The Labial Plosive in Kiribati, ICU Working Papers in Linguistics 10: 31-36. http://id.nii.ac.jp/1130/00004623/

Villegas, Julián, Konstantin Markov, Jeremy Perkins, Seunghun J. Lee (2020) Prediction of creaky speech by recurrent neural networks using psychoacoustic roughness, IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing 14(2): 355 - 366 (https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTSP.2019.2949422) (peer-reviewed)

Lee, Seunghun J. & Reiko Aso (2020) The *LONG-C constraint and word-initial aspirates in Hateruma Yaeyama, a southern Ryukyuan language. Educational Studies 62: 39-47. (peer-reviewed)

Edited Books/Journals

Seunghun J. Lee, Yuko Abe, and Daisuke Shinagawa (eds.) Descriptive materials of morphosyntactic microvariation in Bantu vol. 2: A microparametric survey of morphosyntactic microvariation in Southern Bantu languages Tokyo: ILCAA, 2021, pp. 428+xiv. (ISBN: 9784863373433). http://repository.tufs.ac.jp/handle/10108/99960

Seunghun J. Lee and William Bennett, eds. (2020) Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus, Vol. 60: Festschrift for Prof. Akinbiyi Akinlabi on his 60th birthday.

Guillemot, Céleste, Shin-ichiro Sano and Seunghun J. Lee, eds. (2020) ICU Working Papers in Linguistics 10: Festschrift for Prof. Junko Hibiya in the occasion of her retirement from ICU.

Hara, Yurie, Shigeto Kawahara and Seunghun J. Lee, eds. (2019) ICU Working Papers in Linguistics 7: Festschrift for Prof. Tomoyuki Yoshida on his 60th birthday

Niiya, Machi and Audrey H. Lai, eds. (2019) ICU Working Papers in Linguistics 5: Selected Papers about the Kiribati language with additional materials.

Book chapters

Lee, Seunghun J. (to appear) Depressors. In: Oxford Guide to the Bantu Languages. Oxford University Press.

Lee, Seunghun J. & Elisabeth Selkirk (2022, in print) Xitsonga Tone: the Syntax-Phonology Interface. In (eds.) Haruo Kubozono, Junko Ito & Armin Mester (eds.), Prosody and Prosodic Interfaces. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Recent Presentations by members

Kim, Allen and Seunghun J. Lee (2022) The perceptions and experiences of Zainichi men as fathers in Urban Japan. Kyujangak Symposium. January 28, 2022.

Kamano, Shigeto, Yuko Abe, Kumiko Miyazaki, Seunghun J. Lee (2022) Prosodically prominent clitic: the exclusive particle tu in Swahili. Prosody and Grammar 6, January 30, 2022.

Chan, Le Xuan, Keitaro Mitsuhashi, Kotone Sato, Rina Furusawa, Rin Tsujita, Seunghun J. Lee (2022) The prosodic realizations of accented words after NPI: Gender-based differences. Japanese Prosody and Grammar 6, January 30, 2022.

Muto, Hikaru, Yuri Ibara, Masaki Fukuda, Seunghun J. Lee, Tomoyuki Yoshida (2022) Aging Effects on Comparative Sentences Processing of Japanese Native Speakers. Linguistics Fest 2022, January 29, 2022.

Riedel, Kristina and Seunghun J. Lee (2021) Focus word order and Penultimate Lengthening in Bantu languages, the SLE conference session: workshop 20 (organized by Dr. Maia Duguine and Dr. Aritz Irutzun). September 2, 2021.

Lee, Seunghun J. (2021) Intonation of Xitsonga Pronouns. The 58th Annual Meeting of Japan Association for African Studies (JAAS). May 23, 2021. Hosted by Hiroshima University, Held in Zoom.

Lee, Seunghun J. (2021) The prosody of weak and strong pronouns in Xitsonga. Roundtable Prosody of Pronouns. May 19, 2021. University of Frankfurt am Main (hosted by Frank Kügler).

Lee, Seunghun J. (2021) Reading of the book chapter by Lee & Selkirk (to appear) "A modular theory of the relation between syntactic and phonological constituency" The Phonology-Morphology Circle of Korea. May 15, 2021 @ Zoom.

Hong, Shen and Seunghun J. Lee (2021) The internal structure of prosodic words and tone sandhi Nuosu Yi. Phonology Festa 2021. March 8-9, 2021.

Lee, Seunghun J. and Woonho Choi (2021) A quantitative study of the syntax-prosody interface in two varieties of Korean. Phonology Festa 2021. March 8-9, 2021.

Sreekumar, P., Seunghun J. Lee and Daehan Won (2021) Information sharing with minority Dravidian languages: a case of COVID-19 Myth Busters. The 7th International Conference on Language Documentation and Conservation (ICLDC). University of Hawai'i, USA. March 6, 2021.

Kunzang Namgyal, Jigmee Wangchuk Bhutia and Seunghun J. Lee(2021) Language planning during the pandemic: a Drenjongke (Bhutia) language survey. The 7th International Conference on Language Documentation and Conservation (ICLDC). University of Hawai'i, USA. March 5, 2021.

Timee, Tekonnang and Seunghun J. Lee (2021) Two types of rising intonation in Kiribati interrogatives. Prosody and Grammar Festa 5, TCP, PAIK, NINJAL. February 21, 2021.

Asai, Honoka, Chan, Le Xuan, Sato, Kotone, Suzuki, Michinori, Lee, Seunghun J. (2021) A preliminary study of the prosody of Japanese DP with two adjectival modifiers. 言語学フェス2021. January 24, 2021.

Oho, Atsushi, Suzuki, Michinori, Ashida, Mana, Hasegawa, Rika, Nakayama, Sachiko, Ibara, Yuri, Muto, Hikaru, Lee, Seunghun J. (2021) Collecting perception data from senior citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic. 言語学フェス2021. January 24, 2021.

Seunghun J. Lee (2020) Voice quality research using the Electroglottography (EGG). SNU Workshop on Empirical and Laboratory Linguistics (SWELL): 2020 Winter Workshop. December 23, 2020.

Ashida, Mana, Seunghun J. Lee, Kunzang Namgyal (2020) Building a Part-of-Speech Tagged Corpus for Drenjongke (Bhutia). The 1st Conference of the Asia-Pacific Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 10th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, December 7, 2020. [AACL-IJCNLP 2020]

Abe, Yuko, Seunghun J. Lee, and Daisuke Shinagawa (2020) A Morphosyntactic Survey of Microvariation of Southern Bantu languages: A pilot case of collaborative linguistic research in African contexts. Korea Association of African Studies (KAAS) Conference on the Second Half of 2020. December 4, 2020. pp. 29-42.

Lee, Seunghun J., and Daehan Won (2020) Sharing information across cultures: COVID-19 Myth Busters from WHO. The 2020 International Conference of the Korean Association for Multicultural Education, Seoul National University, December 3-5, 2020.

Lee, Seunghun J. (2020) Acoustics of vowel phonation in Burmese Mon. The 34th General Meeting of the Phonetic Society of Japan. September 26-27, 2020.

Lee, Seunghun J. and Céleste Guillemot (2020) Voiceless nasals in Drenjongke (Bhutia). International Webinar on Languages of North East India Organized by the Centre for Naga Tribal Language Studies, Nagaland University, Kohima Campus. August 8, 2020.

Lee, Seunghun J. and Daehan Won (2020) COVID-19 Myth Busters from WHO in World Languages. Colang 2020: Institute on Collaborative Language Research: COVID Impacts Session. June 25, 2020 [Montana Local Time].

Guillemot, Céleste, Seunghun J. Lee and Jeremy Perkins (2020) The retroflex tongue position in Drenjongke (Bhutia). 2020 Summer Southeast Asia Conference Program. Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Seoul, Korea, June 19, 2020.

Guillemot, Céleste and Seunghun J. Lee (2020) Phonetic Variation of a Phonological Target: Voiceless Nasals in Drenjongke. 日本音韻論学会2020年度春期研究発表会 The Spring Meeting of the Phonological Society of Japan 2020. June 19, 2020.

Lee, Seunghun J. (2020) A phonetic study of non-coalescence of /h/ in the Jeolla dialect of Korean. Korea Round Table, Kyoto Japan. May 29, 2020 (collaboration with Julián Villegas and Mira Oh).

Lee, Seunghun J. (2020) Voicing and phonation in African languages using Electroglottograph. The 57th Annual Meeting of the Japan Association of African Studies. Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. May 23-24, 2020.

Lee, Seunghun J. (2020) Converging linguistics terms in Korean phonology. The First International Conference on Linguistic Terminology, Glossing and Phonemicization (LiTGaP 2020), Denkoku no Mori, Yonezawa City, Yamagata, Japan. Feb. 22–24, 2020.

Lee, Seunghun J., Céleste Guillemot, Le Xuan Chan and Mana Ashida (2020) Intonation of questions in Drenjongke (Bhutia). Prosody and Grammar Festa 4. February 15-16, 2020 @ Kobe University

Recent invited talks by members

Lee, S. J. (2021) EGG SWELL workshop.

Lee, S. J. & Céleste Guillemot (2020). Phonological representation of voiceless nasals in Drenjongke (Bhutia). York University, Toronto. November 27, 2020.

Lee, S. J. & Céleste Guillemot (2020). Voiceless nasals in Drenjongke (Bhutia). International Webinar on Languages of North East India Organized by the Centre for Naga Tribal Language Studies Nagaland University, Kohima Campus. August 8, 2020. [Youtube Video]

Lee, S. J. Voicing phenomena in Korean and Japanese: an electroglottograph study, The 27th Japanese/Korean Linguistics Conference. Sogang University, Seoul, Korea. October 18-20, 2019. (collaboration with Mira Oh)

Lee, S. J. Phonetic fieldwork in linguistic research. Guest Lecture at the University of South Pacific, Laucal campus. Suva, Fiji. August 20, 2019.

Lee, S. J. Aspects of Kiribati: perspectives from acoustic recordings. Professional Development Workshop at Kiribati Teachers' College, Tarawa, Kiribati. August 13, 2019.

Lee, S. J. Phonetics of understudied languages. Professional Development Workshop at Kiribati Teachers' College, Tarawa, Kiribati. August 13, 2019.

Lee, S. J. Second Language Pronunciation in foreign language education. Professional Development Workshop at Kiribati Teachers' College, Tarawa, Kiribati. August 13, 2019.

Lee, S. J. Language documentation with Field Language Explorer (FLEx). Professional Development Workshop at Kiribati Teachers' College, Tarawa, Kiribati. August 13, 2019.

Lee, S. J. Segment-tone interaction in two Tibeto-Burman languages: Drenjongke and Dzongkha (音段和聲調之間的相互關係: 以兩種藏緬語錫金語和不丹語為例). University of Macau. March 27, 2019.

Lee, S. J. What Drenjongke (Bhutia) tells us about human language? Colloquium. Makhim, Sikkim. March 14, 2019.

Lee, S. J. Multi Track Audio Editing Workshop. Makhim, Sikkim. March 14, 2019.

Lee, S. J. Phonetics and Phonology of segment-tone interaction in two Tibeto-Burman languages: Drenjongke and Dzongkha. Linguistics Colloquium, University of Delhi. March 8, 2019.

Lee, S. J. Workshop on Praat. ReNeLDA seminar at University of Dar es Salaam. February 22-26, 2019, University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

===

Migration Professionals And Researchers | Facebook

https://m.facebook.com › groups › permalink

Allen KIM (Int'l Christian Univ.) & Seunghun J. LEE (Int'l Christian Univ.): “The Perceptions and Experiences of Zainichi Men as Fathers in Urban Japan”.

===

© 2020

Towards a Systemic Theory of Irregular Migration

Explaining Ecuadorian Irregular Migration in Amsterdam and Madrid

Authors

(view affiliations)

Gabriel Echeverría

This open access book provides new comparative, empirical, qualitative material on irregular migration

Nests the understanding of irregular migration within a more general sociological interpretation of contemporary society

Gives an alternative theoretical framework and critical review of irregular migration

Open Access Book

2Citations

7Mentions

25kDownloads

Part of the IMISCOE Research Series book series (IMIS)

Download book PDF

Download book EPUB

Buying options

Softcover BookEUR 49.99Price excludes VAT (Australia)

ISBN: 978-3-030-40905-0

Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

Exclusive offer for individuals only

Free shipping worldwide

Shipping restrictions may apply, check to see if you are impacted.

Tax calculation will be finalised during checkoutBuy Softcover Book

Hardcover BookEUR 49.99

Learn about institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (8 chapters)

About this book

Search within book

Front Matter

Pages i-xii

Introduction

Gabriel Echeverría

Pages 1-7 Open Access

Theoretical Study

Front Matter

Pages 9-9

The Study of Irregular Migration

Gabriel Echeverría

Pages 11-39 Open Access

Irregular Migration Theories

Gabriel Echeverría

Pages 41-94 Open Access

Understanding Irregular Migration Through a Social Systems Perspective

Gabriel Echeverría

Pages 95-125 Open Access

Empirical Study

Front Matter

Pages 127-127

Methodological Note

Gabriel Echeverría

Pages 129-138 Open Access

Ecuadorian Migration in Amsterdam and Madrid: The Structural Contexts

Gabriel Echeverría

Pages 139-181 Open Access

Ecuadorian Irregular Migrants in Amsterdam and Madrid: The Lived Experience

Gabriel Echeverría

Pages 183-226 Open Access

Conclusion

Front Matter

Pages 227-227

Steps Towards a Systemic Theory of Irregular Migration

Gabriel Echeverría

Pages 229-246 Open Access

Australia’s Afghan resettlement response a bitter disappointment - Refugee Council of Australia

Australia’s Afghan resettlement response a bitter disappointment

21 January 2022

3 min read

Media release

21 January 2022

The Australian Government’s refugee resettlement response to the Afghanistan crisis is so bitterly disappointing that it will leave Afghan Australians and their millions of supporters across the Australian community feeling betrayed, the Refugee Council of Australia (RCOA) says.

RCOA chief executive officer Paul Power said the four-year commitment announced today of just 10,000 humanitarian places and 5000 family reunion places was hopelessly inadequate, given the scale of need and the generosity of Australian responses to past crises.

“In 2015, Tony Abbott’s Government committed itself to a special additional allocation of 12,000 visas for refugees from Syria and Iraq on top of the annual humanitarian program. This resulted in 39,146 Syrians and Iraqis being resettled over the four years from July 2015,” Mr Power said.

“Today, Scott Morrison’s Government has offered no additional humanitarian places and committed only to allocating places from a global humanitarian program which it cut by 5000 places a year from 2020.

“Today we learn that visas for the 4300 Afghan nationals evacuated from mid August will not be part of any additional commitment, as was widely expected. This means there will be fewer than 11,000 refugee and family visas over the next four years for those not part of the evacuation process.

“In just five months, Australia has received applications from more than 145,000 Afghan nationals in desperate circumstances. What is clear now is that very few of those people have any hope of building a life of safety in Australia.”

Ahmad Shuja Jamal, a special advisor to RCOA who was a senior official in the government of Afghanistan prior to the Taliban takeover in August, said Australia was missing an opportunity to have a positive impact in the region with its greatly delayed and deeply inadequate response.

“Urgent and immediate action at scale is required to protect Afghans under threat. There is no time to waste: Taliban are intensifying their crackdown on women, minorities and those who oppose them by the day,” Mr Jamal said.

“Australia’s refugee resettlement policy is not just about Australia: it can send powerful signals to countries bordering Afghanistan to be more receptive to Afghans seeking safety.

“By anouncing numbers that reflect the true scope of the problem in Afghanistan, Australia can show that these countries are not alone in shouldering the responsibility.”

Ahmad Shuja Jamal and Paul Power are available for further comment and interviews through our media team on 0488 035 535.

Afghanistan Ahmad Shuja Jamal Asia-Pacific Asylum Australia Citizenship COVID-19 Refugee and Humanitarian Program Resettlement Shuja Jamal

Tuesday, January 25, 2022

Squatting (Australian history) - Wikiwand

Squatting (Australian history)

Connected to: QueenslandMelbourneEmancipist

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Squatting is a historical Australian term that referred to someone who occupied a large tract of Crown land in order to graze livestock. Initially often having no legal rights to the land, squatters became recognised by the colonial government as owning the land by being the first (and often the only) European settlers in the area. Eventually, the term "squattocracy", a play on "aristocracy", came into usage to refer to squatters and the social and political power they possessed.

Evolution of meaning

Colonial artist S. T. Gill supports Aboriginal land rights and condemns the Squattocracy in Squatter of N. S. Wales: Monarch of all he Surveys, 1788 (above) and Squatter of N. S. Wales: Monarch of more than all he Surveys, 1863 (below).

The term 'squatter' derives from its English usage as a term of contempt for a person who had taken up residence at a place without having legal claim. The use of 'squatter' in the early years of British settlement of Australia had a similar connotation, referring primarily to a person who had 'squatted' on Aboriginal land for pastoral or other purposes. In its early derogatory context the term was often applied to the illegitimate occupation of land by ticket-of-leave convicts or ex-convicts (emancipists).

From the mid-1820s, however, the occupation of 'unoccupied' land without legal title became more widespread, often carried out by those from the upper echelons of colonial society. As wool began to be exported to England and the colonial population increased, the occupation of pastoral land for raising cattle and sheep progressively became a more lucrative enterprise. 'Squatting' had become so widespread by the mid-1830s that Government policy in New South Wales towards the practice shifted from opposition to regulation and control. By that stage, the term 'squatter' was applied to those who occupied land under a lease or license from the Crown, without the negative connotation of earlier times.

The term soon developed a class association, suggesting an elevated socio-economic status and entrepreneurial attitude. By 1840 squatters were recognized as being amongst the wealthiest men in the colony of New South Wales, many of them from upper and middle-class English and Scottish families. As unoccupied land with frontage to permanent water became more scarce, the acquisition of runs increasingly required larger capital outlays. A "run" is defined in Christopher Pemberton Hodgson's 1846 Reminiscences of Australia, with Hints on the Squatter's Life as: "land claimed by the Squatter as sheepwalks, open, as nature left them, without any improvement from the Squatter."[1]

Eventually the term 'squatter' came to refer to a person of high social prestige who grazes livestock on a large scale (whether the station was held by leasehold or freehold title). In Australia the term is still used to describe large landowners, especially in rural areas with a history of pastoral occupation. Hence the term Squattocracy, a play on 'aristocracy'.

Background and history

When the First Fleet established a settlement at Sydney Cove in 1788 the colonial government claimed to own all of Australia east of the 135th meridian east, ignoring any Indigenous claims to the land. Land that had been deemed 'unoccupied' by Europeans was described as Crown land. Governors of New South Wales were given authority to make land grants to free settlers, emancipists (former convicts) and non-commissioned officers. When land grants were made they were often subject to conditions such as a quit rent (one shilling per 50 acres (200,000 m2) to be paid after five years) and a requirement for the grantee to reside on and cultivate the land. In line with the British government's policy of concentrated land settlement for the colony, governors of New South Wales tended to be prudent in making land grants. By the end of Governor Macquarie's tenure in 1821 less than 1,000 square miles (2,600 km2) of land had been granted in the colony of New South Wales.

During Governor Brisbane's term, however, land grants were more readily made. In addition regulations introduced during Brisbane's term enabled settlers to purchase (with his permission) up to 4,000 acres (16 km2) at 5s an acre (with superior quality land priced at 7s 6d). During Governor Brisbane's four years in office the total amount of land in private hands virtually doubled.[2]

The impetus for squatting activities during this early phase was an expanding market for meat as the population of Sydney increased. The first steps in establishing wool production in New South Wales also created an increased demand for land. Squatting activity was often carried out by emancipist and native-born colonists as they sought to define and consolidate their place within society.[3]

Darling and the 'Limits of Location'

Warfare between squatters and Aborigines in South Australia

1845 political cartoon by Edward Winstanley, critical of Governor George Gipps' land reforms

From 1824 there were acts and regulations to limit squatting. The limits of location, also known as the Nineteen Counties, were defined from 1826; beyond these limits land could not be squatted on or subdivided and sold. This was because of the expense of providing government services (police ...etc.) and difficulty supervising convicts over a wide tract of land. However the nature of the sheep industry which required access to vast grassy plains meant that despite the limitations, squatters often occupied land far beyond the colony's official limits. From 1833 Commissioners of Crown Lands were appointed under the Encroachment Act to manage squatting.

From 1836 legislation was passed to legalise squatting with grazing rights available for ten pounds per year. This fee was for a lease of the land, rather than ownership, which is what the squatters wanted. The 1847 Orders in Council divided land into settled, intermediate and unsettled areas, with pastoral leases of one, eight and 14 years for each category respectively. From here on, squatters were able to purchase parts of their land, as opposed to just leasing it.

It is known that many squatters fought battles with advanced European weapons against the local Indigenous Australian communities in the areas they occupied,[4] though such battles were rarely investigated. These battles/massacres are the subject of the history wars, being the term for an ongoing public discussion on Australia's interpretation of its history. Squatters were only occasionally prosecuted for killing indigenous people. The first conviction of white men for the massacre of Indigenous people followed the Myall Creek massacre in 1838, in which Aboriginal subject status was employed by colonial courts for the rare co-incidence of local, colonial and imperial authorities.

Whilst life was initially tough for the squatters, with their huge landholdings many of them became very wealthy and were often described as the "squattocracy". The descendants of these squatters often still own significant tracts of land in rural Australia, though most of the larger holdings have been broken up, or, in more isolated areas, have been sold to corporate interests.

In April 1844 Governor Gipps made two regulations with the intention of remodelling the squatting system. The first, gazetted on 2 April, permitted squatters to occupy runs on payment of £10 for every 20 square miles (52 km2). The second regulation allowed squatters after 5 years occupancy to purchase 320 acres (130 hectares) of a run and gave purchasers security of tenure over a whole run for another 8 years. 150 squatters gathered in Sydney later in the month of April and protested against Gipps's changes drafting a petition to the Queen and forming the Pastoral Association of New South Wales - the first formalising of the identity of squatters as a political group.

A large squatting demonstration was held in Melbourne in June 1844. The lessees of the Crown lands came into Melbourne on horseback, and marched to the place of the meeting with flags flying, preceded by a Highland piper playing martial airs. At this meeting petitions were adopted to be transmitted to the several branches of the Home and Colonial Legislatures, requesting alterations in the law of Crown lands and a total separation from the Middle District (New South Wales). A new association was formed at this meeting, and designated the 'Pastoral Society of Australian Felix'.[5]

Legislation to allow selection

In the 1860s several colonies passed legislation to permit selection.

Victoria

In the colony of Victoria, the 1860 Land Act allowed free selection of Crown land, including that occupied by pastoral leases.

Queensland

The process of land selection in Queensland began in 1860 and continued under a series of land acts in subsequent years.[6] Separated from New South Wales in 1859, land was considered the new Queensland colony’s greatest asset and its prosperity as a colony was measured according to the extent of land settlement. Rent from land leases was the colony’s largest revenue earner. The initial political contest was between the squatters who controlled large tracts of land and the new immigrants who wanted small land holdings. The resumption of squatters' land for division into smaller farms (known as closer settlement) was promoted by the Queensland Government to attract immigrants to Queensland. Although Queensland legislation was framed with the aim of a comprehensive land policy, lobbying by both groups led to numerous rule changes about the conditions of occupacy of the land and who had priority. Consequently there were over 50 principal and amending acts covering all land legislation up to 1910.[6]

New South Wales

Map of squatting districts in New South Wales in 1844.

The squatters' grip on agricultural land in the colony of New South Wales was challenged in the 1860s with the passing of Land Acts that allowed those with limited means to acquire land. With the stated intention of encouraging closer settlement and fairer allocation of land by allowing 'free selection before survey', the Land Acts legislation was passed in 1861. The relevant acts were named the Crown Lands Alienation Act and Crown Lands Occupation Act. The application of the legislation was delayed until 1866 in inland areas such as the Riverina where existing squatting leases were still to run their course. In any case severe drought in the Riverina in the late 1860s initially discouraged selection in areas except those close to established townships. Selection activity increased with more favourable seasons in the early 1870s.

Both selectors and squatters used the broad framework of the Land Acts to maximise their advantages in the ensuing scramble for land. There was a general manipulation of the system by squatters, selectors and profiteers alike. The legislation secured access to the squatter's land for the selector, but thereafter effectively left him to fend for himself. Amendments passed in 1875 sought to remedy some of the abuses perpetrated under the original selection legislation.

However discontent was rife and a political shift in the early 1880s saw the setting up of a commission to inquire into the effects of the land legislation. The Morris and Ranken committee of inquiry, which reported in 1883, found that the number of homesteads established was a small percentage of the applications for selections under the Act, especially in areas of low rainfall such as the Riverina and the lower Darling River. The greater number of selections were made by squatters or their agents, or by selectors unable to establish themselves or who sought to gain by re-sale. The Crown Lands Act of 1884, introduced in the wake of the Morris-Ranken inquiry, sought to compromise between the integrity of the large pastoral leaseholds and the political requirements of equality of land availability and closer settlement patterns. The Act divided pastoral runs into Leasehold Areas (held under short-term leases) and Resumed Areas (available for settlement as smaller homestead leases) and allowed for the establishment of local Land Boards.[7]

South Australia

Prior to 1851, squatters paid a licence fee of £10 per year (regardless of area), with no surety of tenure from one year to the next. After 1851, leases could be acquired for 14 years, with annual rent.[8] The Strangways Land Act in 1869 provided for replacing large pastoral runs with closer-settled more intensive farming.

Political and social legacy

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

A significant proportion of squatters opposed the movement for self-determination by workers that gained impetus in the last decades of the 19th century in Australia. The events of the shearers' strike of 1891 and the harsh counter-measures by Government and squatters left a bitter legacy that adversely affected class relationships in the ensuing decades.

The Squatter's Daughter, painting by George Washington Lambert

The Squattocracy have historically retained close ties to Britain. Many families retained properties in both Britain and Australia, often retiring to Britain after making their fortune and leaving vast stretches of land to be controlled by hired staff or younger sons.[9]

Prominent Australian families from the "squattocracy" include:

The Kidman family who held 107,000 square miles worth of land in Central Australia.[10] Members and relatives include Nicole Kidman and the "Cattle Baron" Sydney Kidman.

The Ellis family of South Australia.[11]

The Forrest family of Western Australia who have produced a number of conservative politicians for the Liberal Party; Alexander Forrest, David Forrest, John Forrest (Western Australia's first Premier) and Mervyn Forrest.

The Gilbert family of South Australia.[12]

The Baillieu family of Victoria who were awarded the title of Baron's Baillieu in recognition for the immense contributions to Australian society made by the politician and financier Sir Clive Baillieu, son of public legend William Baillieu, after whom the Baillieu library at Melbourne University is named.

Cultural resonances

Literature: The power of the squatters, including their affinity with the police, is referenced in Banjo Paterson's "Waltzing Matilda", Australia's most famous folk song.

Clara Morison by Catherine Helen Spence explores the power of Australia to transform those with a lowly social station in Britain into the Aristocracy of a new world.[13]

Mary Theresa Vidal's 1860 novel Bengala is an Austenesque social comedy exploring the evolution of the pseudo-aristocratic manners which define the squattocracy.[13]

In Miss Fisher's Murder Mysteries, the title character, The Honourable Phyrne Fisher, is resistant to her class and acts as a contrast to her Aunt Prudence, who typifies grazier and squattocracy snobbery.

The film Australia deals with the failure of many large grazier properties in the mid-twentieth century, as well as the Squattocracy's close historic links with the British Aristocracy, with whom they frequently intermarried. The film's star, Nicole Kidman, is herself a relative of the prominent Squatter family the Kidmans, who, at the height of their power, held 107,000 square miles worth of land in Central Australia.[10]

The strategy board game Squatter is named for the term.

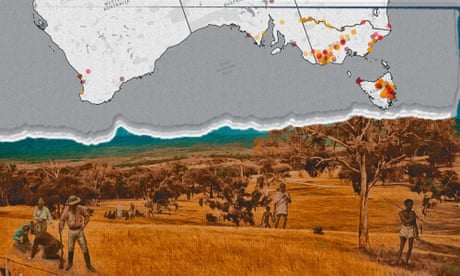

The killing times: the massacres of Aboriginal people Australia must confront | Frontier wars | The Guardian

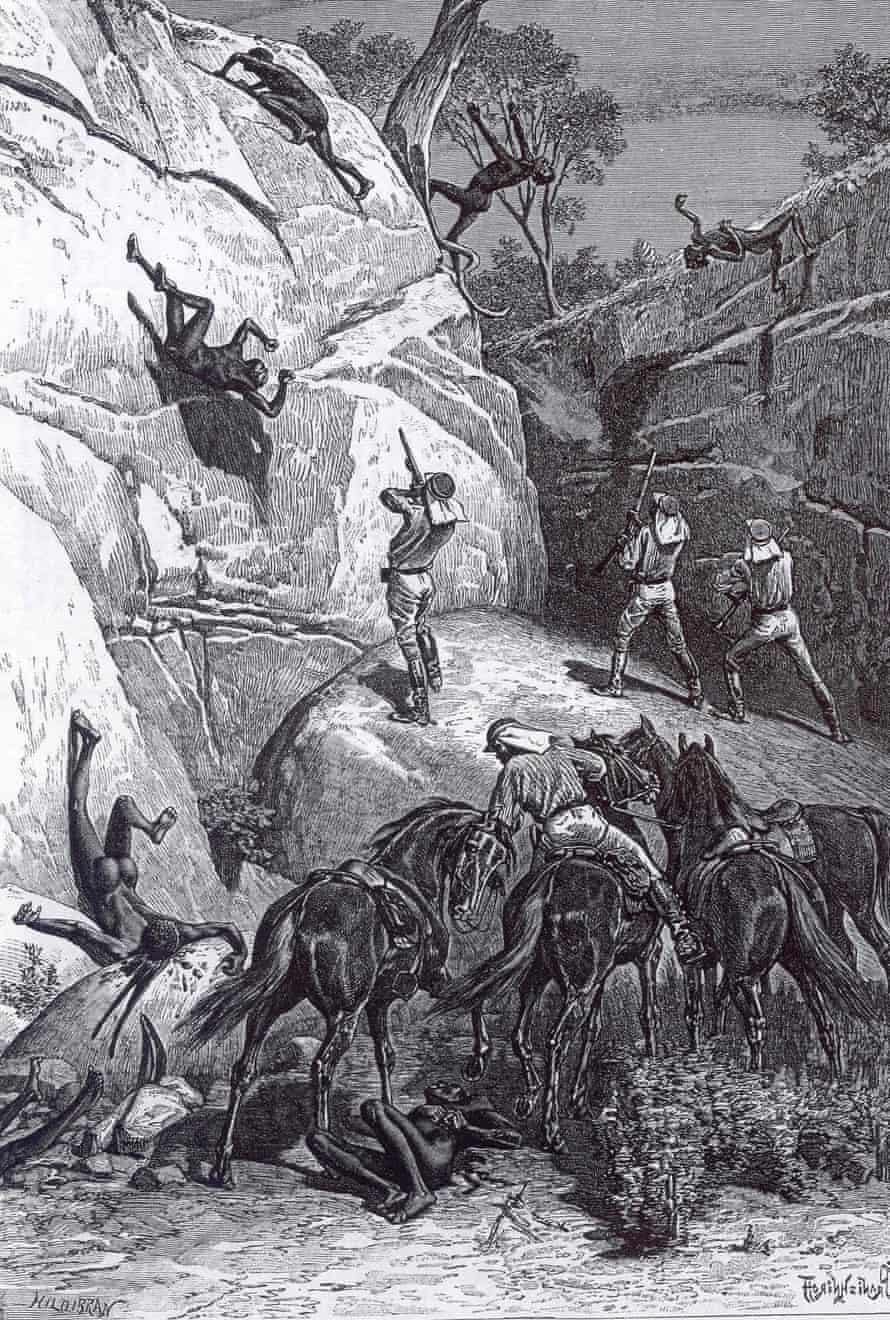

The killing times: the massacres of Aboriginal people Australia must confront

Special report: Shootings, poisonings and children driven off cliffs – this is a record of state-sanctioned slaughter

The truth of Australia’s history has long been hiding in plain sight.

The stories of “the killing times” are the ones we have heard in secret, or told in hushed tones. They are not the stories that appear in our history books yet they refuse to go away.

The colonial journalist and barrister Richard Windeyer called it “the whispering in the bottom of our hearts”. The anthropologist William Stanner described a national “cult of forgetfulness”. A 1927 royal commission lamented our “conspiracy of silence”.

But calls are growing for a national truth-telling process. Such wishes are expressed in the Uluru statement from the heart. Reconciliation Australia’s 2019 barometer of attitudes to Indigenous peoples found that 80% of people consider truth telling important. Almost 70% of Australians accept that Aboriginal people were subject to mass killings, incarceration and forced removal from land, and their movement was restricted.

The Killing Times is a Guardian Australia special report that aims to assemble information necessary to begin truth telling – not just the grim tally of more than a century of frontier bloodshed, but its human cost – as told by descendants on all sides. This is the history we have all inherited.

Our interactive map details massacres in every state and territory but the research is ongoing. It does not count all the sites of conflict, or clashes over land and resources, in which lives were lost in the colonisation of Australia.

The numbers we have drawn on are conservative estimates.

There are more massacre sites to be added – places where the true death toll may never be known – and many more we are still working to verify, particularly in Queensland, Western Australia, the Northern Territory and New South Wales.

In this first snapshot of the continent, we have found that there were at least 270 frontier massacres over 140 years, as part of a state-sanctioned and organised attempt to eradicate Aboriginal people.

Starting in 1794, mass killings were first carried out by British soldiers, then by police and settlers – often acting together – and later by native police, working under the command of white officers, in militia-style forces supported by colonial governments.

These tactics were employed, without formal repercussions, as late as 1926.

Using data from the colonial massacre map at the University of Newcastle’s Centre for 21st Century Humanities, and adopting its stringent research methods, Guardian Australia has surveyed the rest of the country.

We found that:

Government forces were actively engaged in frontier massacres until at least the late 1920s.

These attacks became more lethal for Aboriginal people over time, not less. The average number of deaths of Aboriginal people in each conflict increased, but from the early 1900s casualties among the settlers ended entirely – with the exception of one death in 1928.

The most common motive for a massacre was reprisal for the killing of settler civilians but at least 51 massacres were in reprisal for the killing or theft of livestock or property.

Of the attacks on the map, only once were colonial perpetrators found guilty and punished – in the aftermath of the Myall Creek killings in 1838.

In NSW and Tasmania between 1794 and 1833, most of the 56 recorded attacks were carried out on foot by detachments of soldiers from British regiments, and an average of 15 people were killed in each one. The weapon most often used was the “Brown Bess” musket, which was issued to British forces in the Napoleonic wars.

In NSW and Victoria between 1834 and 1859, horses and carbine rifles were used in at least 116 frontier massacres of Aboriginal people in mostly daytime attacks, with an average of 27 people killed in each attack.

From the late 1840s, massacres were carried out as daylight attacks by native police, sometimes in joint operations with settlers. They most often used double-barrelled shotguns, rifles and carbines.

Preliminary data from Queensland shows that between 1859 and 1915 an average of 34 people were killed in each attack.

There are at least nine known cases of deliberate poisoning of flour given to Aboriginal people.

There were also efforts to cover up the atrocities.

In 1927 a royal commission into the Forrest River massacre in Western Australia concluded that a police party had killed at least 11 people then burned their bodies in makeshift ovens. In his report the commissioner, GT Wood, said a “conspiracy of silence” in the entire Kimberley district had thwarted attempts to find out what really happened.

These massacres are challenging to read about. It can be even more challenging to discover a personal or family connection to them. Nevertheless, many Australians have come forward to share their stories, some for the first time.

Sandy Hamilton is descended from a soldier in the 46th Regiment which, on orders of the NSW governor Lachlan Macquarie, killed at least 14 Aboriginal people at Appin in 1816.

“We need to take ownership of our history,” Hamilton says. “We deserve to know the truth of how we came to be who we are.

“Then we can also make real choices about who we want to be as a society, as Australians.”

Liza Dale-Hallett is a great-niece of George Murray, a police constable who led the killings at Coniston in 1920, in which at least 50 Aboriginal men, women and children died. Warlpiri, Anmatyerre and Kaytetye people say up to 170 were slaughtered.

“It happened all over Australia and this is a part of our history,” Dale-Hallett says. “I’ve got a direct connection to it – but that doesn’t make it my history and not yours.

“Part of the reason they are continuing to cause harm is they haven’t been properly acknowledged. The simple act of listening is a really important first step in a more complex conversation that needs to be had about how did Australia settle itself.”

A descendant of Coniston survivors, Francis Jupurrurla Kelly, agrees.

“We want everyone to understand why so many of our innocent men, women and children were murdered in cold blood,” he says.

“Many kartiya [whitefellas] were too greedy for our land and didn’t see us as fully human.

“We can only come together as one mob, if everyone, starting with all our schoolchildren and our elected representatives, knows what has happened to our loved ones and why, so they are never forgotten.”

In replicating the University of Newcastle’s centre’s data collection methods we have only recorded attacks in which six or more people were killed.

According to the centre’s Prof Lyndall Ryan, the massacre of six undefended Aboriginal people from a hearth group of 20 is known as a “fractal massacre”, so called because it leaves survivors vulnerable to further attack and far less able to hunt, care for children or carry out cultural obligations to country.

Research and verification of the evidence takes time and care. It involves locating primary sources such as letters, journals, newspaper articles, books, photographs and oral histories.

Photograph: David Dare Parker/The Guardian

We have relied on the written record of the time but acknowledge that, for example, a settler’s journal is not necessarily a reliable or definitive account of what took place. There can be a tendency to understate the severity of the attacks, the toll they took and the actions of those present.

The written records don’t always indicate intention. Sometimes they do, in chilling detail, as described in this letter from a Gippsland squatter, Henry Meyrick, to his family in England in 1846:

The blacks are very quiet here now, poor wretches. No wild beast of the forest was ever hunted down with such unsparing perseverance as they are. Men, women and children are shot whenever they can be met with … I have protested against it at every station I have been in Gippsland, in the strongest language, but these things are kept very secret as the penalty would certainly be hanging.

We have categorised killings according to the alleged reasons for them as written in primary sources we have seen, but oral histories provide context. Aboriginal attacks on settlers often took place after previous unreported killings of smaller groups or individuals, or as the result of escalating tensions over land, water and resources. Settler reprisals were heavily disproportionate and grew worse over time.

The language in these sources is coded. “Dispersal” is a common euphemism. “Land clearing”, “expeditions” and “hunting parties” were undertaken to “teach the blacks a lesson”.

Learning about this history will come as a shock to some. But Australians trying to move past blame or guilt are coming forward now in greater numbers, and their voices are only growing louder.

“We have done a lot already to make sure nobody has an excuse to stay ignorant,” Francis Jupurrurla Kelly says. “It’s now time for governments and others to do their bit to tell the truth and help us move forward together.”