Want to read

Buy on Kobo

Rate this book

Edit my activity

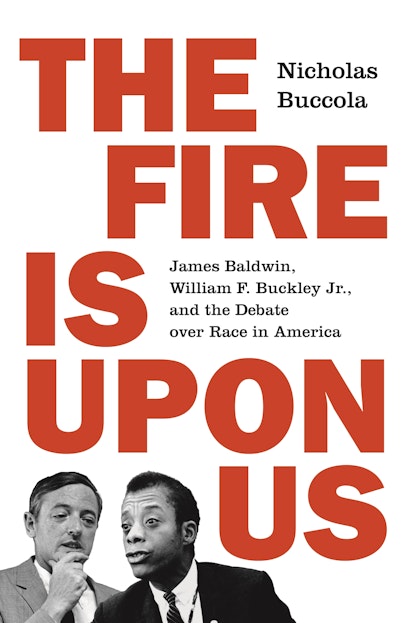

The Fire Is upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate over Race in America

Nicholas Buccola

4.48

1,153 ratings204 reviews

How the clash between the civil rights firebrand and the father of modern conservatism continues to illuminate America's racial divide

On February 18, 1965, an overflowing crowd packed the Cambridge Union in Cambridge, England, to witness a historic televised debate between James Baldwin, the leading literary voice of the civil rights movement, and William F. Buckley Jr., a fierce critic of the movement and America's most influential conservative intellectual. The topic was "the American dream is at the expense of the American Negro," and no one who has seen the debate can soon forget it. Nicholas Buccola's The Fire Is upon Us is the first book to tell the full story of the event, the radically different paths that led Baldwin and Buckley to it, the controversies that followed, and how the debate and the decades-long clash between the men continues to illuminate America's racial divide today.

Born in New York City only fifteen months apart, the Harlem-raised Baldwin and the privileged Buckley could not have been more different, but they both rose to the height of American intellectual life during the civil rights movement. By the time they met in Cambridge, Buckley was determined to sound the alarm about a man he considered an "eloquent menace." For his part, Baldwin viewed Buckley as a deluded reactionary whose popularity revealed the sickness of the American soul. The stage was set for an epic confrontation that pitted Baldwin's call for a moral revolution in race relations against Buckley's unabashed elitism and implicit commitment to white supremacy.

A remarkable story of race and the American dream, The Fire Is upon Us reveals the deep roots and lasting legacy of a conflict that continues to haunt our politics.

GenresHistoryNonfictionPoliticsRaceSocial JusticeBiographyAudiobook

...more

496 pages, Hardcover

First published October 1, 2019

Book details & editions

291 people are currently reading

4276 people want to read

About the author

Nicholas Buccola7 books44 followers

Follow

Readers also enjoyed

King of Kings: The Iranian Revolution—A Story of Hubris, Delusion and Catastrophic Miscalculation

Scott Anderson

4.47

794

Begin Again: James Baldwin's America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own

Eddie S. Glaude Jr.

4.39

6,279

Money, Lies, and God: Inside the Movement to Destroy American Democracy

Katherine Stewart

4.22

1,302

When the Clock Broke: Con Men, Conspiracists, and How America Cracked Up in the Early 1990s

John Ganz

4.07

4,054

The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations

Toni Morrison

4.31

4,145

The Long '68: Radical Protest and Its Enemies

Richard Vinen

3.43

197

Reagan: His Life and Legend

Max Boot

4.16

1,752

Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics

Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò

3.99

3,733

Authority: Essays

Andrea Long Chu

3.83

593

The Fire Next Time

James Baldwin

4.55

118k

Game Change: Obama and the Clintons, McCain and Palin, and the Race of a Lifetime

John Heilemann

4.13

22.8k

Dylan Goes Electric!: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties

Elijah Wald

3.97

2,628

Freedom’s Dominion: A Saga of White Resistance to Federal Power

Jefferson R. Cowie

4.49

844

Everyone Who Is Gone Is Here: The United States, Central America, and the Making of a Crisis

Jonathan Blitzer

4.47

8,126

The Pursuit of Happiness: How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined America

Jeffrey Rosen

4.29

674

Baldwin: A Love Story

Nicholas Boggs

4.39

238

Be a Revolution: How Everyday People Are Fighting Oppression and Changing the World—And How You Can, Too

Ijeoma Oluo

4.37

1,124

Black AF History: The Un-Whitewashed Story of America

Michael Harriot

4.6

7,190

Tar Baby

Toni Morrison

3.99

23.5k

Humanly Possible: Seven Hundred Years of Humanist Freethinking, Inquiry, and Hope

Sarah Bakewell

4.01

2,119

All similar books

Ratings & Reviews

My Review

Sejin

3 reviews

Want to read.

Rate this book

Write a Review

Friends & Following

No one you know has read this book. Recommend it to a friend!

Community Reviews

4.48

1,153 ratings204 reviews

5 stars

674 (58%)

4 stars

370 (32%)

3 stars

97 (8%)

2 stars

12 (1%)

1 star

0 (0%)

Search review text

Filters

Displaying 1 - 10 of 204 reviews

Kusaimamekirai

711 reviews271 followers

Follow

December 21, 2019

“What concerns me the most, is that unless we can talk to each other and hear each other, the days of reason are numbered. When reason loses its authority, violence fills the vacuum.”- James Baldwin

“There is never time in the future in which we will work out our salvation. The challenge is in the moment, the time is always now.”- James Baldwin

“We should focus on the necessity to animate [the] particular energy in the black community that has served other minority groups well throughout American history." -William F. Buckley

I am an unrepentant James Baldwin fan. I believe he was one of the most important voices on race in the 20th century and someone whose voice continue to resonate well into 21st century. William Buckley however, did not share my enthusiasm for James Baldwin or his ideas.

In this extremely intriguing book, the author examines these two men, the debate they staged at Cambridge Union in 1965, and the social forces they grew up and flourished in.

The author’s portrait of Baldwin is admittedly more flattering than that of Buckley, who he clearly has little love for (a position which, as one reads this book, comes to be completely understandable), but he never discounts Buckley’s impact on the 1950s and 1960s and the Conservative movement which it can rightly be said he nurtured.

At issue in this debate, and the larger social debate at large is the question: “The American dream is at the expense of the American Negro”.

For Baldwin this was an indisputable truth and one that by 1965 he had spent the better part of his life writing about. Central to his writings was the idea that the hate whites showed toward blacks, while obviously harmful to the well being of black men and women, paled in comparison to the spiritual damage it was wreaking on white people and the nation at large. The source of this hate for Baldwin was based above all else in fear:

“ ‘One of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, that they will be forced to deal with pain’ But this, Baldwin could see, would not do, for hatred, ‘could destroy so much and it never failed to destroy the man who hated and this was an immutable law.’ "

Until white America come to terms with its fear, it could never really begin to move forward.

William Buckley on the other hand believed it was black people who were holding themselves back. While acknowledging that American history is replete with examples of black people suffering at the hands of white people, Buckley believed that federal intervention such as civil rights laws, busing, and integration of schools, buses and lunch counters was unconstitutional. How then you ask do we right this wrong?

According to Buckley the only way forward was for blacks to wait until whites were ready to move forward. As blacks were uneducated (the causes for this perceived lack of education he doesn’t elaborate on) they were incapable of voting responsibly and therefore were better off under a system of benign paternalism. In addition, whites (particularly Southern whites) were entitled to their way of life and if didn’t include sitting with blacks in restaurants that wasn’t an issue for the federal government to intervene in.

To be fair, Buckley also advocated for less people to vote irrespective of their race, and yet it is quite breathtaking to read his writings and remember that he is seen today as the darling of “serious” conservative thought. Buckley was by his own admission hostile to democracy and seemingly would have been much more comfortable in a monarchy or dictatorship (providing of course as George W. Bush once quipped ‘I’m the dictator’).

As the author neatly summarizes:

“Buckley’s position was hostile to both democratic and liberal values. He was far less concerned with the demand that all human beings should have a say in their political destiny, or that all individuals have rights that ought to be protected, than he was with the idea that those who were best suited to preserve civilization were authorized to do what was necessary to achieve this goal.”

While many seemingly found, and continue to find, Buckley charming or erudite, it is difficult for me to find his beliefs anything less than repellent. Baldwin, after a televised debate with Buckley, would say much the same:

“I was trying to do what Martin was doing. I still hoped people would listen. But Bill’s a bully, he can’t listen, he uses weapons I simply won’t use. I said people who live in the ghetto don’t own it; it’s white people’s property. I know who owns Harlem. He (Buckley) said ‘Do the landlords tippy-toe uptown and throw garbage out the windows?’ And I tuned out. If a cat said that to me in life, I’d simply beat the hell out of him. He was saying Negroes deserved their fate; they stink. To my eternal dishonor, I cooled it, I drew back and I lost the debate. I should have beat him over the head with the coffee cup. He’s not a serious man. He’s the intellectuals’ James Bond”

Buckley liked to consider himself intellectually superior to the George Wallace’s and Bull Connor’s of the world in that he never openly espoused the hate that they would. Rather he crafted his racism in rhetorical turns of phrase that in many ways were far more dangerous than anything Wallace or Connor did. Buckley was, unlike them, a man of ideas and through his ideas he created a movement that exists to this day and espouses many of the beliefs he helped foster.

32 likes

2 comments

Like

Comment

Faith

2,200 reviews669 followers

Follow

February 14, 2020

“The American Dream is at the expense of the American Negro”. That was the topic of the 1965 debate between James Baldwin and William F Buckley, Jr. held at the Cambridge Union. The actual debate is included in the Epilogue of the audiobook. The sound quality is a little iffy, especially for Buckley who seemed to roam away from the microphone, but it was fascinating to hear these men. However, the debate itself is only a small part of this book.

The book covers the parallel lives of Baldwin and Buckley and what shaped them. There is an analysis of their published works within the context of contemporaneous events. It also covers politics, the civil rights movement in the United States and the profoundly divergent views of the 2 men. Baldwin wanted change, while Buckley defended the maintenance of traditional American patterns (which was just a way of maintaining white supremacy without actually mentioning race). I got a great deal more than I was expecting from this book. The extensive research was incorporated so well that the book never felt like a recitation of facts. Each man expressed some extreme and controversial views and the book was evenhanded in its approach. It’s really an exceptional book.

audio overdrive

24 likes

Like

Comment

Mehrsa

2,245 reviews3,588 followers

Follow

October 4, 2019

This book was fantastic! So well-written and so timely. I had watched that stunning Oxford debate years ago and I've also read practically everything Baldwin has ever written and most of Buckley's work as well. They were both excellent writers and thinkers though Baldwin was clearly the superior intellect. This book is less about the two men than it is about two reactions toward racism in America. If it had ended at Buckley vs. Baldwin, the latter would clearly have won the future, but I think the right got a lot better at articulating their opposition to civil rights activism. Buckley believed and was fine stating his belief of white superiority even as he couched his opposition in states rights. When the VRA was overturned recently, no one but some fringe right wing people explicitly championed the idea that fewer people voting was actually better. Buckley did. It was just so fascinating to read missives from across time from people across the aisle and think about how much as changed and how much hasn't.

24 likes

Like

Comment

Steve Llano

100 reviews12 followers

Follow

January 8, 2020

This book is an excellent example of what rhetoricians and those interested in the scholarship of debate and argumentation can produce. Unfortunately, this book was written by a political scientist. I am afraid it is an excellent example of something that rhetorical critics should be doing - long view, multimedia analysis of rhetorical responses between intellectuals on issues they care about.

This book is not a treatment of the Cambridge debate between Baldwin and Buckley. I bought it in order to read that account, and I was certainly not disappointed. Buccola spends 2 chapters of the book on the details of the night of the debate, including excellent analysis of what was said and how those in that audience, and the BBC audience responded or could have interpreted what was said. These two chapters alone are fantastic and serve as an excellent example of scholarly inquiry on a text that is identified primarily as a traditional debate.

But where the book shines is Buccola's expansion of the sense of debate as something well beyond a simple presentation held at a university between speakers. Buccola correctly frames the night at Cambridge as one iteration of a long-running engagement between these two thinkers on the question of civil rights for African-Americans in the 1950s and 1960s. Although they only directly engage two or three times in their lives, the nature of written or spoken discourse aimed at a larger audience for the purpose of changing feelings or thoughts (aka rhetoric) has a visceral effect or impact of being seen as a debate, albeit happening across 2 decades. This book seems similar to the treatment of the Lincoln Douglas Debates that was given by Zarefsky in a treatment in the 1990s, and more recently (but less effectively) in a book by Allen Guelzo. This book can serve as a model for re-thinking events known as "debates" as flash phenomena of larger debates occurring out of clear sight, much like the mushroom - we only see the stalks and call them mushrooms, but the organism is underground, out of sight, and all around us, larger than we think.

Buccola spends a good amount of time trying to work through the positions of Buckley and Baldwin on race and civil rights, and is fair to both men. I believe his treatment of Buckley's racism is very thoughtful, complex, and appropriate. I know I would have had a lot of trouble trying to present those ideas as workable, and Buccola does a very good job. James Baldwin, as we learn in the book, is dedicated to the idea that we should try to learn to see things from the perspective of all involved. Buccola takes that idea to heart in his treatment of Buckley, who quite honestly has some hair-raising opinions about non-white Americans.

The book is excellent, and is high quality history and rhetorical scholarship. Well written, thoroughly researched, and thoughtful, it is a great book if you are interested in the very direct, rhetorical reactions of two writers to violent, horrible, and powerful events going on around them. Both of them feel compelled to try to change the minds of others with text. That unites them, and also drives the narrative of the book. It's fabulous reading.

Show more

10 likes

Like

Comment

J Beckett

142 reviews429 followers

Follow

September 17, 2020

My book club had the opportunity to speak with Nicholas Buccola just as The Fire is Upon Us was released, but his humble demeanor hadn't prepared us, in any conceivable way, for what he put on paper. Certainly, The Fire is Upon Us, is one of the most carefully crafted and consciously written books on the work and brilliance of James Baldwin. Fully charged, and unapologetic, Buccola delivers most impressively.

6 likes

Like

Comment

Lauren

1,833 reviews2,543 followers

Follow

April 6, 2024

Unparalleled close study of William Buckley and James Baldwin's careers and writings, leading up to their public debate "Is the American Dream at the the expense of the American Negro" at the University of Cambridge in February 1965. The full transcript of the debate is appended in the book, and also available in several permutations on YouTube, most recently re-cast and scripted by two orators at Cambridge playing each part in the same meeting hall as the original debate.

While the debate is the crux of the book, it is also a dual biography, and a post-mortem of sorts. Buccola compares and contrasts Buckley and Baldwin's upbringings and their tandem rise to the cultural icons that they became in the 1960s-1980s, and their copious writings during the Civil Rights era. Buckley's long shadow on American conservatism continues today, and the book notes Buckley's transitions in messaging over time, and his (convoluted) opinions on political and cultural icons of this era, from George Wallace to Ayn Rand.

I recently read Baldwin's collection Nobody Knows My Name, and this book gave rich context behind many of those essays ("Faulkner and Desegregation", "Fifth Avenue, Uptown", "Fly in the Buttermilk"), and made me eager to continue reading more of his work, and revisit some I've already read.

A good review of THE FIRE IS UPON US from The Atlantic:

The Famous Baldwin-Buckley Debate Still Matters Today by Gabrielle Bellot, December 2019 [free to paywall]

best-of-2024 bios-memoirs politics-policy

...more

8 likes

Like

Comment

Renee

16 reviews27 followers

Follow

November 20, 2019

This book was very helpful in helping me understand the white, educated backlash against dismantling White Supremacy.

2019

7 likes

Like

Comment

Rick Howard

Author 3 books44 followers

Follow

June 19, 2020

**** Recommend it

For an old white man, I try to be cognizant of the world around me. I try to be empathetic to the people who have not had it as easy as me. I understand that I am the epitome of white privilege and I at least try to educate myself about the way of life for citizens of my country who are not. In an ironic twist I find that I am astonished that I knew nothing about James Baldwin before I read this book. If that isn’t the definition of white privilege, I don’t know what is.

I mean, I recognized the name and knew he was a respected literary scholar, but I knew no context. In my entire lifelong education, nobody every handed me any of his writings and suggested I should read them. How is it that I did not know? His idea about the white man, who pushes American exceptionalism at the expense of the black man, hurts the white man as much as the black is a revelation to me. The white man’s hypocrisy that is illuminated with Baldwin’s spotlight is like a punch to the gut. In his debate speech at Cambridge, when he switches the pronoun for the black slave from they to I, it made me weep.

"Let me put it this way, that from a very literal point of view, the harbors and the ports, and the railroads of the country–the economy, especially of the Southern states–could not conceivably be what it has become, if they had not had, and do not still have, indeed for so long, for many generations, cheap labor. I am stating very seriously, and this is not an overstatement:

*I* picked the cotton,

*I* carried it to the market,

and *I* built the railroads

under someone else’s whip for nothing.

For nothing.

The Southern oligarchy,

which has still today so very much power in Washington, and therefore some power in the world, was created by my labor and my sweat, and the violation of my women and the murder of my children.

This, in the land of the free, and the home of the brave.

And no one can challenge that statement.

It is a matter of historical record.”

And finally, when he discusses the black man’s hopelessness when he realizes that not only is the deck stacked against him in his lifetime, but that his children have no chance either, I just want to raise my fist in the air and scream.

In the same vein, I did not know that William F. Buckley, the founder of the conservative movement in America, was an elitist, states-rights, religious, racist, bigot. He wasn’t a klu-klux-klan level racist that advocated violence, but his writings and speeches convinced the religious right in the seats of power to do nothing about the situation. Even thou he lost the debate to Baldwin in 1965, he helped win the war in the long run. The conservatives keep winning and the black man never does.

history

6 likes

Like

Comment

Lynn

3,377 reviews69 followers

Follow

July 29, 2020

Excellent book about the debate between William F. Buckley and James Baldwin at Cambridge University on February 28,1965. Their topic was “the topic was “the American Dream is at the expense of the Americas Negro”. William F. Buckley took the side that Negros weren’t civilized enough to take full responsibility for full citizenship. Baldwin took the side that America needs to get itself together and include Blacks for full participation in the American Dream (citizenship rights). It was decided that Baldwin won but the legend of the debate lived on. Baldwin died young but Buckley was long haunted by his opinions and the experience. The book covers the the two men’s lives and experiences in order to give insight into their beliefs. The debate and its aftermath are covered. I always thought it was a tough debate to watch (used to be on YouTube) but this book made it more accessible and fun. The book itself is very enjoyable and helped me think of something we’re losing, instead of shaming and silencing someone a conversation in a controlled setting might be important. I also was involved in a conversation about All in the Family that brought up the topic too. And it’s Norman Lear’s birthday. Happy Birthday Norman!

5 likes

Like

Comment

Stetson

530 reviews322 followers

Follow

November 16, 2022

Interesting, a lot of ink has been spilled about the brief debate between the literary luminary and social critic, James Baldwin, and the father of modern American conservatism, William F. Buckley Jr., at The Cambridge Union in February 1965. I say this because in watching the debate itself and the loaded yet vague debate proposition ("The American Dream is at the expense of the American Negro"), it is hard to see its effect on the trajectory of racial politics at that time (civil right act had already become law) or its historical relevance to race relations today (other than our discourse continues to circle the same questions and sloppily pointing to Buckley's position in this debate allows progressive a cheap way to score points against conservatives). The debate does very little to even symbolize some cosmic conflict of visions between the Left and Right given that Baldwin's position is more moralizing and morose than the left of his time and Buckley hoped to actually consolidate different types of right-wingers under his particular ideological project (Frank Meyer's fusionism) but only ever managed to do so during the 80s and early 90s. To me, the preoccupation with this debate arises from our (as in America's) contemporary obsession with racial politics and our love of celebrity culture. Baldwin and Buckley are elite and niche intellectuals but celebrities nonetheless. Their performances are both erudite and compelling (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Tek9...), and their pairing is interesting in that it's a rare juxtaposition of two quite different intellectuals. Though in other ways, it is remarkable that Baldwin and Buckley paths crossed so minimally (even in print), especially because of Baldwin's close relationship with Norman Podhoretz, the Commentary editor who eventually joined Buckley's ideological project after becoming disaffected with the New Left in the late 60s.

After all this throat-clearing, we can finally address Nicholas Buccola's The Fire is Upon Us. This work is a close inspection of the Baldwin vs Buckley debate, which is the works climactic event. Most of the work is composed of interlaced biographical sketches of each figure combined with psychological and philosophical analysis of their written works on race and politics. Buccola's analysis is fair and accurate for the most part, but is more astute when it comes to Baldwin's ouerve. The author is clearly more familiar with Baldwin's work, which is forgivable in that Buckley's body of work is quite capacious, especially if his editorial choices at and leadership of National Review is considered, which of course it must be and is. Some of this gap in familiarity with Buckley may have induced Buccola to be overly critical when representing Buckley's positions on civil rights and race relations generally. The major oversight being that Buckley's position on civil rights changed significantly in the years after the debate, including Buckley's open acknowledgement that federal intervention was needed to end segregation, his strong criticism of George Wallace in 1968, and his “Why We Need a Black President in 1980" piece written in 1970.

I do think Buccola's stinging critique of Buckley's racial positions and politicking pre-1964 are warranted and reasonable (despite some of the presentism it relies on) in most respects, but he should have trained the same scrutiny on Baldwin's ideas as well, including his "morose nihilism" (a charge of Buckley against Baldwin) and his flirtations with radicalism. Instead Buccola is mostly a partisan of Baldwin's on all questions and to a minor extent tries to indict conservative ideas more broadly as inherently retrograde and immoral. I think it is reasonable to highlight like Buccola does how Buckley's willingness to entertain segregationist and anti-civil rights arguments in NR despite largely playing coy on that question himself or advocating gradual liberalization was likely incentivized by the composition of his readership and political strategy. But it is unfair to use Buckley's pre-1964 position on race to claim that, "his goal was to maintain white domination of the South, one way or the other." A closer and more accurate reading of Buckley shows that Buckley hoped that cultural change and local politics would improve the conditions and status of black Americans. Moreover, Buckley quickly realized that his pre-1964 prescriptions for race relations were inadequate for that moment and embraced civil rights.

I also wish that Buccola dissected Baldwin's argument about race in America a bit more. Some of Baldwin's ideas still animate many claims about race today made by progressives. His primary claim is that racism allows low-status white Americans to lay false claim to self-esteem and dignity because they can point to the relatively lower position of blacks. This is morally degrading to both parties. Baldwin also holds that this racial hierarchy is perpetuated by a willful blindness by whites generally about the injustices attendant to race. Thus, continued to immiserate and ghettoize blacks because the true problem must be ignored. There is some internal tension in this claim in that it implies that white Americans benefit from both race-consciousness and race-blindness. It's a tension that isn't resolved by Baldwin. Moreover, it doesn't respond to Buckley's point that Ameica is indeed quite concerned with improving life for black Americans and is likely to see those improvement if its founding ideals are fulfilled: “I challenge you to name another civilization anytime, anywhere, in the history of the world in which the problems of a minority is as much the subject of dramatic concern as it is in the United States.”

Despite Buccola's obvious rooting interest affecting his analysis and his distance from and enmity toward conservative thought, The Fire Is Upon Us is an interesting work. It was engaging to learn about Baldwin's ideas concerning literary criticism. For instance, he lambasted protest novels and primarily ideological works of art as hollow (an astute point I've intuitively felt for awhile). He felt that placing politics first in art erects barriers to emotional and psychological depth. I look forward to reading more Baldwin, and think others will enjoy Buccola's work if they're deeply interested in mid-century America political and cultural thought.

Other reviews of The Fire Is Upon Us I'd recommend:

https://lawliberty.org/the-fire-and-t...

https://www.nationalreview.com/magazi...

An extended review can be found here --> https://stetson.substack.com/p/baldwi...

biography history non-fiction

...more

3 likes

2 comments

Like

Comment

Displaying 1 - 10 of 204 reviews

More reviews and ratings

===

The Fire Is upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate over Race in America

On February 18, 1965, an overflowing crowd packed the Cambridge Union in Cambridge, England, to witness a historic televised debate between James Baldwin, the leading literary voice of the civil rights movement, and William F. Buckley Jr., a fierce critic of the movement and America’s most influential conservative intellectual. The topic was “the American dream is at the expense of the American Negro,” and no one who has seen the debate can soon forget it. Nicholas Buccola’s The Fire Is upon Us is the first book to tell the full story of the event, the radically different paths that led Baldwin and Buckley to it, the controversies that followed, and how the debate and the decades-long clash between the men continues to illuminate America’s racial divide today.

Born in New York City only fifteen months apart, the Harlem-raised Baldwin and the privileged Buckley could not have been more different, but they both rose to the height of American intellectual life during the civil rights movement. By the time they met in Cambridge, Buckley was determined to sound the alarm about a man he considered an “eloquent menace.” For his part, Baldwin viewed Buckley as a deluded reactionary whose popularity revealed the sickness of the American soul. The stage was set for an epic confrontation that pitted Baldwin’s call for a moral revolution in race relations against Buckley’s unabashed elitism and implicit commitment to white supremacy.

A remarkable story of race and the American dream, The Fire Is upon Us reveals the deep roots and lasting legacy of a conflict that continues to haunt our politics.

Q&A with Nicholas Buccola

James Baldwin’s Reckless Idea

Listen in: The Fire Is upon Us

Book Club Discussion Questions

Awards and Recognition

- Winner of the Frances Fuller Victor Award for General Nonfiction, Oregon Book Awards

- Shortlisted for the Ralph Waldo Emerson Award, Phi Beta Kappa Society

- Shortlisted for the MAAH Stone Book Award, Museum of African American History

- One of Whoopi Goldberg's Favorite Things, ABC The View

- New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice

- Chicago Tribune writer John Warner's Book That Will Help You Better Understand the Messed-Up Nature of the World

- One of The Undefeated's 25 Can't Miss Books of 2019

- One of The Progressive's Favorite Books of 2019

- One of LitHub's 50 Favorite Books of the Year

- One of Inside Higher Ed's Books to Give the Educator in Your Life for the Holidays

No comments:

Post a Comment