https://theconversation.com/guide-to-the-classics-ruth-parks-harp-in-the-south-is-a-story-about-aboriginal-country-207419

Biripi/Worimi actor Guy Simon as Charlie Rothe (Daniel Boud/STC) and Harp in the South author Ruth Park (right).

Guide to the classics: Ruth Park’s Harp in the South is a story about Aboriginal Country

Published: October 12, 2023

Author

Senior lecturer in literature, film and new media, Australian National University

Dr Monique Rooney receives financial and in-kind support as the 2023 Nancy Keesing AM Fellow at the State Library of NSW, where she is researching the papers of Ruth Park in preparation for writing a literary biography.

Partners

Australian National University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

====

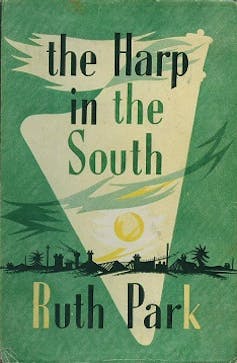

Ruth Park’s novel The Harp in the South (1948) is a classic of Australian fiction. Just as television viewers in recent decades would recognise “Ramsay Street” as the fictional centre of Australia’s longest-running television soap opera Neighbours, earlier generations of readers would have recognised with affection “Twelve-and-a-half Plymouth Street”: the hearth and home of Harp’s fictional Irish-Australian family, the Darcys.

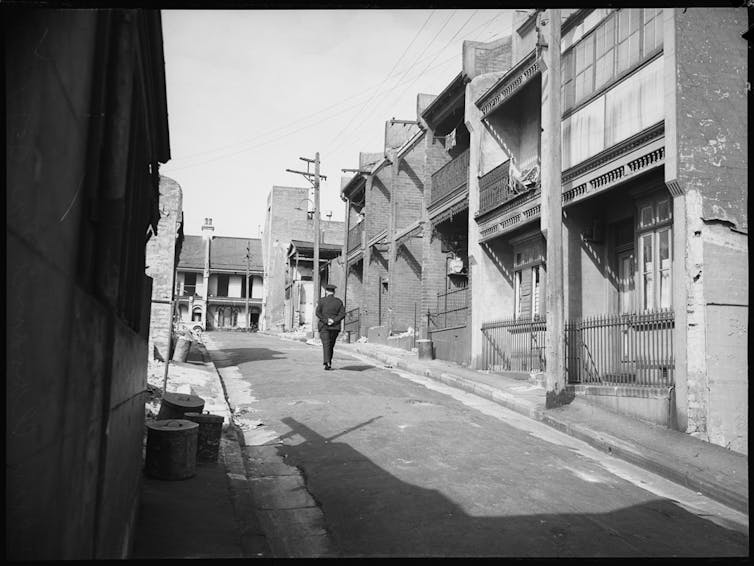

This fictional street exists in an actual inner-urban neighbourhood, and this mattered to how the novel was first read. Readers of the time expressed strong reactions to Harp’s depiction of Sydney’s Surry Hills.

The novel depicts the built, settler-colonial environment of Surry Hills, along with other parts of the land First Nations people know as “Country”. On first publication in Australia at least, character Charlie Rothe’s Aboriginal ancestry – and his relation to Country – appear to have passed unremarked.

Harp in the South depicts the settler-colonial environment of Surry Hills. SLNSW

‘Dickens from Australia’ grew up in New Zealand

The novel was first serialised in the pages of the Sydney Morning Herald, after winning the newspaper’s first novel-writing competition. It became an instant hit. Fans impatient to read the latest instalment joined long queues outside newsstands and bookstalls.

But not all readers were enamoured with it. One Sydney resident called it a “wallow in depravity, filth and crime” that should “be banned from the homes of many decent citizens”, in the Herald’s double-page spread of responses to the book.

In her own letter to the Herald, responding to the moral panic her novel had generated, Park wrote that her intention was to show how “splendid characters full of honesty and loving kindliness, can exist against a squalid and often tragic background”.

US author Sterling North named Park the “Female Dickens from Australia”. But Park was not originally “from Australia”. She was born in Auckland, New Zealand.

Interestingly, in letters to long-term pen-friend and future husband D’Arcy Niland, written before 1942 when she migrated to Australia and married him, Park signs off with such Māori salutations as “Kia Ora” and refers to her home country as Māoriland.

Ruth Park, D'Arcy Niland and their children. Mitchell Library State Library of New South Wales

Read more: Friday essay: 'the problem is that my success seems to get in his way' – the fraught terrain of literary marriages

The hills are full of Irish people

The hills are full of Irish people. When their grandfathers and great-grandfathers arrived in Sydney they went naturally to Shanty Town, not because they were dirty or lazy, though many of them were that, but because they were poor.

These lines introduce the novel’s Darcy family, whose loves and losses animate the pages that follow. Grandma Darcy loves to smoke her “little clay cutty” in bed. Family patriarch Hughie Darcy argues with fellow resident and Orangeman Patrick Diamond, especially when Hughie is affected by the “demon drink”. Hughie’s alcoholism impoverishes an already poor family.

Hughie’s devoutly Catholic wife, Margaret “Mumma” Darcy, mourns the loss of her eldest child, Thady, who had one day wandered away from the front doorstep where he had been playing. Mumma searches for, but never finds, this missing boy.

Roie (Rowena) is the elder of the two Darcy daughters. Through her, Park explores sex outside of marriage, unwanted pregnancy and abortion – the topics that unsettled readers on first publication. After she becomes pregnant following a night with local boy Tommy Mendel, Roie seeks out the back-alley services of a woman who administers abortions.

Afraid and ashamed, Roie flees the scene, only to be violently assaulted by a gang of drunken sailors whom she has the misfortune of encountering on her way home. They beat her to the ground, precipitating a miscarriage.

Roie’s crisis coincides with another emerging story: that of Charlie Rothe, who will come to live at Twelve-and-a-Half Plymouth Street as her husband. Something in this story reverberates down the decades, summoning recognition of an historical tragedy.

Read more: Surry Hills was once the centre of New South Wales’ ‘rag trade’: a short history of fashion manufacturing in Sydney

Who is Charlie Rothe?

Charlie Rothe appears in the story as Roie is recovering from the miscarriage and its ongoing side-effects. Roie is overcome by dizziness at the live venue of a radio quiz her sister Dolour has just won. Charlie suddenly appears and helps her to a seat.

This stranger is introduced via the narrator’s description of his voice.

Noises were already fast fading into a babble of sound. Then a voice said, “What’s the matter? Are you feeling sick?”

It was a hollow, echoing voice like thunder on a heath. Roie tried to answer it and couldn’t. It sounded again, frightening her a little, then she felt someone lower her into a seat.

Like Emily Bronte’s Heathcliff, Charlie is an orphan child whose unknown origins become the source of speculation about parentage and race.

This speculation arises when Charlie becomes part of the Darcy household. Dolour and Mumma ask Charlie about his parents, having assumed he is an Aboriginal man.

“They died when I was about seven, I think,” responds Charlie, who knows only that a “bagman” had raised him. “He just picked me up, I was sitting by a fence, yowling my head off, and he asked me to come along with him, and I went.” At this point, Charlie’s “eyes looked back into the past and saw the endless dusky, dusty roads of New South Wales”.

Biripi/Worimi actor Guy Simon as Charlie Rothe in the Sydney Theatre Company’s production of Harp in the South. Daniel Boud/STC

True to her declared intention to create “splendid” yet “squalid” characters against a “tragic” background, Park does not shy away from depicting Hughie and Mumma’s prejudices toward Charlie.

They fear Roie and Charlie will one day have a child, imagining what it would mean to nurse “a sooty grandchild”. Yet, Hughie and Mumma will come to love both Charlie and their granddaughter.

Read more: Wuthering Heights, Emily Brontë and the truth about the 'real-life Heathcliff'

A mixed-race romance

For Roie does give birth to Charlie’s child. They name her “Moira”, an Irish name meaning both “drop of the sea” and “destiny, fate”. With its romance between an Irish-Australian woman and an Aboriginal man, Harp stands apart from white-authored novels of the time, whose depictions of Aboriginal characters reflect eugenicist beliefs that Aboriginal people were a “dying race”

.

Ruth Park and D'Arcy Niland further Literary Papers Collection Box MLMSS, Author provided (no reuse)

Charlie loves Roie and she loves him. However, in the sequel novel, Poor Man’s Orange, Roie dies giving birth to her and Charlie’s second child, Michael. Charlie is rocked by her death, but eventually he and Roie’s sister, Dolour, develop an intimate attachment. Charlie will have a future with Dolour, as do his children with Roie, Moira and Michael.

A relative stranger to Australian shores, Park brought into her novel an Aboriginal character who had become estranged from both his people and his Country. So it’s significant that, in the concluding chapter of Poor Man’s Orange, Charlie asks Dolour to come “outback” with him and the children.

The Macquarie Dictionary defines “outback” as “remote, sparsely inhabited back country” that had been “romanticised in some Australian literature”. Given that his memory is of a “dusky, dusty” New South Wales road, Charlie’s “outback” is not quite the same space as that conjured in certain white-authored worlds.

Toward the end of Poor Man’s Orange, three years after Roie’s death, Charlie and Dolour go walking at night to the shores of Botany Bay. Charlie proposes to her that she come with him “outback”, and she accepts.

Music spilled across the street like the yellow light that spilled from the tall corner-lamp slung in its archaic wrought-iron bough. But mainly there was silence, as though already Surry Hills felt its doom, and down in the earth the old grass-roots were stirring, ready to clothe this soil with the verdure that had been there a century before.

It is not an Aboriginal character who faces his doom: it is Surry Hills, an urban environment built by colonial-settlers.

Read more:

Ruth Park and D'Arcy Niland further Literary Papers Collection Box MLMSS, Author provided (no reuse)

Charlie loves Roie and she loves him. However, in the sequel novel, Poor Man’s Orange, Roie dies giving birth to her and Charlie’s second child, Michael. Charlie is rocked by her death, but eventually he and Roie’s sister, Dolour, develop an intimate attachment. Charlie will have a future with Dolour, as do his children with Roie, Moira and Michael.

A relative stranger to Australian shores, Park brought into her novel an Aboriginal character who had become estranged from both his people and his Country. So it’s significant that, in the concluding chapter of Poor Man’s Orange, Charlie asks Dolour to come “outback” with him and the children.

The Macquarie Dictionary defines “outback” as “remote, sparsely inhabited back country” that had been “romanticised in some Australian literature”. Given that his memory is of a “dusky, dusty” New South Wales road, Charlie’s “outback” is not quite the same space as that conjured in certain white-authored worlds.

Toward the end of Poor Man’s Orange, three years after Roie’s death, Charlie and Dolour go walking at night to the shores of Botany Bay. Charlie proposes to her that she come with him “outback”, and she accepts.

Music spilled across the street like the yellow light that spilled from the tall corner-lamp slung in its archaic wrought-iron bough. But mainly there was silence, as though already Surry Hills felt its doom, and down in the earth the old grass-roots were stirring, ready to clothe this soil with the verdure that had been there a century before.

It is not an Aboriginal character who faces his doom: it is Surry Hills, an urban environment built by colonial-settlers.

Read more:

Long before the Voice vote, the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association called for parliamentary representation

The future of an Aboriginal character

It is “down in the earth” that “the old grass-roots were stirring”. The “verdure” that springs back to life matters to how we understand Park’s Aboriginal character and his relationship to Country.

Charlie’s invitation to Dolour to come “outback” with him and his children changes the meaning of “outback”. In this context, “outback” can be understood as Country that had been occupied and cared for long before colonial invasion.

A mixed-race romance survives and thrives at Twelve-and-a-Half Plymouth Street. This is remarkable, given laws against miscegenation had been in place in some Australian states as late as 1940, negatively affecting attitudes to “mixed-descent families”.

Like Charlie and his children, The Harp in the South has had a future. Since publication, it has been adapted for stage, radio and television: both at home and abroad.

Shane Connor (right) played Charlie Rothe on the televised adaptation of the Harp in the South books. Prime Video

In 1987, two years after the first episodes of Neighbours introduced us to its three white families living on Ramsay Street, The Harp in the South miniseries was televised. Actor Shane Connor – who would go on to play Ramsay Street resident Joe Scully – was cast to play Charlie.

The Harp in the South has been translated into 37 languages. It is reputed never to have been out of print. Its enduring popularity is a testament to its author’s very considerable skill as a writer. Park draws on romance and other familiar genres to tell a story about Irish-Australian community in Sydney.

And in 2023, it is possible to see – threaded through the novel – a story about First Nations people, dispossession and ongoing attachment to Country.

Indigenous

Neighbours

Aboriginal

Guide to the Classics

Emily Bronte

Heathcliff

Ruth Park

Get expert voices that rise above the noise.

In a year marked by uncertainty, reliable information has never been more important. When the news is driven by clicks and algorithms, it's easy to lose sight of what truly matters. The Conversation offers a better way, bringing you insights from experts who help inform and not inflame. This year, we've appointed a new Public Policy Editor, based in Canberra. Over the next 12 months, they'll focus on key areas ripe for reform, including the NDIS, tax, housing, climate, productivity and Indigenous affairs. Want to hear this kind of news first? Join 200,000 other Australians who get our FREE daily newsletter, packed with expert insights and analysis.

Get newsletter

Misha Ketchell

Editor

===

===

The future of an Aboriginal character

It is “down in the earth” that “the old grass-roots were stirring”. The “verdure” that springs back to life matters to how we understand Park’s Aboriginal character and his relationship to Country.

Charlie’s invitation to Dolour to come “outback” with him and his children changes the meaning of “outback”. In this context, “outback” can be understood as Country that had been occupied and cared for long before colonial invasion.

A mixed-race romance survives and thrives at Twelve-and-a-Half Plymouth Street. This is remarkable, given laws against miscegenation had been in place in some Australian states as late as 1940, negatively affecting attitudes to “mixed-descent families”.

Like Charlie and his children, The Harp in the South has had a future. Since publication, it has been adapted for stage, radio and television: both at home and abroad.

Shane Connor (right) played Charlie Rothe on the televised adaptation of the Harp in the South books. Prime Video

In 1987, two years after the first episodes of Neighbours introduced us to its three white families living on Ramsay Street, The Harp in the South miniseries was televised. Actor Shane Connor – who would go on to play Ramsay Street resident Joe Scully – was cast to play Charlie.

The Harp in the South has been translated into 37 languages. It is reputed never to have been out of print. Its enduring popularity is a testament to its author’s very considerable skill as a writer. Park draws on romance and other familiar genres to tell a story about Irish-Australian community in Sydney.

And in 2023, it is possible to see – threaded through the novel – a story about First Nations people, dispossession and ongoing attachment to Country.

Indigenous

Neighbours

Aboriginal

Guide to the Classics

Emily Bronte

Heathcliff

Ruth Park

Get expert voices that rise above the noise.

In a year marked by uncertainty, reliable information has never been more important. When the news is driven by clicks and algorithms, it's easy to lose sight of what truly matters. The Conversation offers a better way, bringing you insights from experts who help inform and not inflame. This year, we've appointed a new Public Policy Editor, based in Canberra. Over the next 12 months, they'll focus on key areas ripe for reform, including the NDIS, tax, housing, climate, productivity and Indigenous affairs. Want to hear this kind of news first? Join 200,000 other Australians who get our FREE daily newsletter, packed with expert insights and analysis.

Get newsletter

Misha Ketchell

Editor

===

On ‘The Harp in the South’, by Ruth Park

Delia Falconer

IN OCTOBER 1945, just three months after Japan’s surrender ended Australia’s role in the Second World War, the Sydney Morning Herald announced that it had set aside £30,000 to stimulate the development of our art and literature, which included a £2,000 prize for best novel. Ruth Park recounts in the second volume of her autobiography, Fishing in the Styx (Penguin, 1993), that she first urged her husband, D’Arcy Niland, to enter, as the young parents had been hard-pressed to make ends meet as full-time writers in the three years they had been married. Instead, it was Park who ended up working hastily on her first novel at her parents’ kitchen table, while visiting her native New Zealand with their two children. In December 1946, Park learned that out of 175 entries, her book about the struggling Irish–Australian Darcy family in Sydney’s Surry Hills had won. The Harp in the South, wrote war poet Shawn O’Leary in the review that accompanied the announcement, ‘bludgeons the reader about the brain, the heart, and the conscience.’ It became an Australian classic, so loved that it is yet to go out of print.

Park was only twenty-eight, but what first strikes one is the extraordinary confidence of her voice. Warm, knowing, and emphatic, it bears a strong resemblance to the big-hearted social realism of American writers of the same era, particularly John Steinbeck. ‘The hills are full of Irish people,’ The Harp in the South begins. ‘When their grandfathers and great-grandfathers arrived in Sydney they went naturally to Shanty Town, not because they were dirty or lazy, though many of them were that, but because they were poor.’ Ex-journalist Park creates a warm, matter-of-fact, and often humorous portrait of slum life, while never letting us forget how its squalid tenements, with their windowless rooms and walls crawling with bedbugs, were hazardous to both health and human potential.

Within the first pages we meet the residents of Twelve-and-a-Half Plymouth Street: staunch Catholic Ruth Darcy, her quasi-alcoholic husband Hughie, and their daughters Roie and Dolour. In an almost casual reference, we also learn about a traumatic event the family has had to absorb: the Darcys had a middle child, Thady, who disappeared from the streets when he was six. This unbearable fact is the emotional key to the book; it is the weight that gives a true sense of the randomness at work in those lives that fall out of society’s care, and it is the suppressed knowledge that grounds Park’s broader-brush portraits and moments of melodrama.

Like Steinbeck’s Cannery Row (Viking Press, 1945), Plymouth Street is a microcosm. Within the Darcy family’s small orbit are Ruth’s sharp Irish mother; the family’s lodgers (Miss Sheily, her retarded son Johnny, and fervent Orangeman Patrick Diamond); Lick Jimmy, the kindly Chinese shopkeeper next door, who bears more than a passing resemblance to Steinbeck’s Lee Chong; and the nuns who run the local school. But what stands out about this novel is Park’s keen interest in women. She wrote at an extraordinary moment in Australian literary history when female authors – including Christina Stead, Florence James and Dymphna Cusack – were pushing our fiction into the intimate territories of women’s lives.

Park fixes her sharp, sympathetic eye on those areas of life that male writers tended to treat sentimentally or disregard: abortion, the exhausting care for children, the difficulties of long marriage, childbirth, and the pleasures of (married) sex. Roie experiences the whole gamut: she falls pregnant to her first boyfriend and plans a risky illegal abortion, but then loses the child by accident; however, despite grieving terribly, she goes on to a joyful married motherhood – all without ever losing her innate goodness and refinement. Through Roie, Park puts a gentle human face on taboo topics, while withholding judgment and the traditional narrative retribution (death, barrenness, or ostracism) that readers might expect. Park treats all of her characters kindly, but it is surely this solidarity with women that has made her book so adored. Certainly, the beating heart of The Harp in the South is smart, indomitable Dolour – prepubescent, hopeful, and as yet unspoiled by slum life. The reader hopes fervently that she will use her education to escape the especially tough road that Surry Hills offers to girls.

Although Park’s working-class background was more genteel, The Harp in the South is the work of an immersed, intelligent observer. Park and Niland married in 1942, when Sydney was in the grips of a catastrophic wartime housing crisis. The only accommodation they could find was in inner-city Surry Hills, built higgledy-piggledy over Sydney’s prehistoric sandhills. While the population had once been mixed, the wealthy had since fled and poor renters crammed into its old, unrenovated tenements. Pregnant and horribly sick with her first child, Park shared a single bed at the top of an old shop with Darcy while his brother Beres slept downstairs in an abandoned barber’s chair. Life here, Park wrote in Fishing in the Styx, was ‘like a visit to some antique island where the nineteenth century still prevailed’ (p. 138). The Surry Hills population’s shocking isolation in time and space is a striking feature of her novel. The cantankerous old coal-fuelled stove, Puffing Billy, is almost another character in Twelve-and-a-Half Plymouth Street. A trip to the beach is a once-in-a-lifetime experience, and even a visit to Paddy’s Markets in town is an adventure. In 1945, Park’s newly wedded life in Surry Hills was still fresh enough to feed into her characters’ suffocating sense of never having a private moment.

Park was also able to use her husband’s Irish–Australian family as a model for the chaotic Darcy clan. Niland, Park records, was remarkably tolerant of his ne’er-do-well alcoholic father, and, to her intense chagrin, of his hard-bitten mother’s longstanding unfriendliness towards her. Park’s novel reflects the sectarianism rife in Australia at this time. She is remarkably adept at recreating the colourful Irish–Australian and working-class vernaculars. She celebrates the fierce clan loyalty among the Darcys – an essential goodness that allows them to endure the unendurable – but laces her portrait with a progressive politics, always pushing against the cruelty of conservative restrictions. When local madam and sly-grogger Delie Stock (a thinly-veiled portrait of Tilly Devine) offers to treat the St Brandan’s pupils to a Christmas picnic, Father Cooley at first refuses to allow the nuns to accept her dirty money – even if it means the sickly children will never see the ocean. Park clearly relishes the scene in which Stock browbeats him into submission.

The Harp in the South also gives us a strong sense of mid-twentieth century Sydney’s inner suburbs as a melting pot. Though one feels uncomfortable today reading her portrait of ‘inscrutable’, lonely Lick Jimmy, he does represent the significant Chinese population of this area (and he is given the same treatment as other stock characters, like Miss Sheily and Mr Diamond – drawn in broad strokes, then endowed with individual, secret lives). Roie’s husband, Charlie Rothe, is a particularly intriguing figure: of Indigenous background, he was found abandoned in country NSW and brought up by an eccentric swagman. One can’t help wondering today if he is part of what we now know as the Stolen Generations. Certainly, the Redfern/Surry Hills area has been an important destination for generations of Aboriginal people separated from their countries by continuing colonial dispossession. Charlie’s ‘blood’ is an issue for the Hughie and Mumma; and yet, in their acceptance of him, Park suggests that working-class solidarity and openness go deeper than surface racism. She is also terrific at giving a sense of the perpetual carnival drama of Sydney’s old inner suburban streets where life was lived so publically, especially in her comic set piece of a New Year’s bonfire that ends in chaos.

But not everyone loved The Harp in the South when it first appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald in twelve daily instalments, beginning on 4 January 1947. In fact, it was controversial even before a word of Park’s text went to print; Angus & Robertson baulked at the novel they had on their hands (though they had to honour a ‘gentleman’s agreement’ to publish the winner), and readers wrote to the newspaper about the synopsis it had released. The Herald went on to publish forty-three responses, a symposium, and a daily tally of pro and con letters (sixty-eight for; fifty-four against).

At the time, Park attributed much of the venom to her portrayal of slum-dwellers as fully rounded human beings rather than a social problem. Yet looking back from the perspective of 1993, she felt the hostility emanated from two particular factors: that she was a New Zealander, and a woman. Certainly, her theory holds water: even today, authorship is often tacitly constructed as ‘male’. The Herald’s prize was aimed at those who had contributed to the war effort, and encouraged both men and women to enter – yet by the time Park won, the women who had held down previously male-only jobs during the war were being forced to give them ‘back’ to returning servicemen. Academic Ross Gibson characterises these postwar years as a deeply unsettled period, and their conservatism as a response to the radical social changes wrought by the war – especially to gender roles and sexual mores – which still ‘simmered’. The intense response to Park – a young, knowing working woman – may have come out of a sense that she was an unwitting representative of profound change, who needed to be put back in her ‘place’. Certainly, the reaction traumatised Park, who said she lost her lifelong faith in people at this time – though she could still write about it with characteristic humour. When she and Niland rented an apartment in Petersham, using the prize money, she recalls, she received a letter addressed to ‘The Harpy in the South’.

Novelist Miles Franklin was also highly critical of the novel, sniping to a friend, ‘It is a shoddy sordid performance of a very phony journalistic book,’ full of ‘catch cries to the gallery’. Certainly, The Harp in the South does owe a debt to the Victorian novel of sensation (emergency blood-letting, death by automobile and self-flagellation are all part of its bright canvas). Yet at the time Park was writing, the social realist novel – with its debt to harder contemporary fact – dominated, especially among women writers, while there was less of today’s perceived distinction between the popular and highbrow (‘literary’ fiction as we know it was not to appear as a distinct marketing category until the 1980s). Popular appeal was also paramount for a working writer. While the Commonwealth Literary Fund provided some grants to established writers, today’s supplementary sources of income, such as teaching, mentoring and festival attendance, which allow an author to hold onto the literary high ground, did not exist. But this lack of pretension has always been Park’s great appeal. She and Niland were romantic figures in the public imagination not only because they were married authors, but because they were jobbing writers, ready to take a shot at any form. As newlyweds, Park and Niland worked out a philosophy of ‘versatility’, and for many years their most reliable source of income was from her ABC radio children’s scripts. Yet it’s shocking to read, in Park’s memoir, just how difficult it was to make a living in an era before protections for Australian authors – dependent on overseas presses – were put in place, especially in terms of territorial copyright, public and education lending rights, and income averaging. (A series of appalling errors by Niland’s overseas publisher meant his bestselling Shiralee (Angus & Robertson, 1955) was filmed virtually without payment.)

This context makes the lasting power of Park’s novel all the more extraordinary. Everything is exceptionally energetic, intensely felt, and endowed with a sense of distinct locality – whether it is the muddy puddles in the old steps of the Darcy home, in which Dolour and Roie always ‘expected to find frogs’, or the smell of vanilla for a Christmas pudding, ‘half flavour and half perfume’. Park has an amazing ability to construct memorable scenes with humour and heart. Long after reading the book, they stay fresh in one’s mind like moments from a film: Hughie thinks he has won the lottery; Hughie and Grandma duel over the Christmas pudding; Grandma, on her deathbed, calls out to an old lover, ‘Stevie, it’s wicked you are, and there’s hellfire under me feet, but I love you, I love you, Stevie. Ah, Stevie!’ Always, Park’s emphasis is on the power of human character, to engage with and transform what it encounters, no matter how impoverished. Her book is itself an embodiment of her Irish–Australian characters’ rich inheritance as observers, talkers and storytellers.

The novel’s impact was great. Only four years after it appeared, Clive Evatt, NSW Minister for State Housing, set about a program of slum clearance. Park would officially open the first block of Devonshire Street flats, though she would later express ambivalence about the loss of community and street life this entailed. She would go on to write a darker sequel, Poor Man’s Orange (Angus & Robertson, 1949) and a prequel, Missus (Penguin, 1985). In 1987, The Harp in the South and Poor Man’s Orange were turned into a hugely successful mini-series, most memorable for a young Kaarin Fairfax’s luminous performance as Dolour.

The Harp in the South still bludgeons us about the heart. I confess that I still tear up reading the last two pages, when Mumma is visited by the spirit of Thady and, realising he died long ago, possesses him again for a moment, ‘little and defenseless and entirely hers’. Park wrote one of the most distinctive and enduring books about her adopted hometown. For all the changes to the old suburb in the prehistoric sandhills, there are moments – especially in summer, when the terraces seem to breath the warm air in and out – that it is still possible, thanks to her vision, to feel its terrible and wonderful old life.

References

Cusack, D 1936, Jungfrau, The Bulletin, Sydney.

Genoni, P 2013, ‘Slumming it: Ruth Park’s The Harp in the South’, in Dalziell, T & Genoni, P (eds.), Telling Stories: Australian Life and Literature, 1935–2012, Monash University Publishing, Victoria, pp. 119–125.

Gibson, R 2000, ‘Where the Darkness Loiters’, History of Pornography, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 251–254.

Hooton, J (ed.) 1996, Ruth Parks: A Celebration, Friends of the National Library of Australia, Canberra, viewed at <http://www.nla.gov.au/sites/default/files/ruth_park_a_celebration.pdf>.

Moore, N 2001, ‘The Politics of Cliché: Sex, Class and Abortion in Australian Realism’, Modern Fiction Studies, vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 69–91.

Parks, R 1993, Fishing in the Styx, Viking, Victoria.

Steinbeck, J 1939, The Grapes of Wrath, The Viking Press, New York.

The Stella Prize 2013, ‘The Stella Count 2013’, The Stella Prize, viewed online.

Share article

===

Summary of ‘The Harp in the South’ by Ruth Park: A Detailed Synopsis

https://newbookrecommendation.com/summary-of-the-harp-in-the-south-by-ruth-park-a-detailed-synopsis/

Table of Contents

Introduction

Synopsis of The Harp in the South

Alternative Book Cover

Characters

Key Takeaways

Spoilers

FAQs about The Harp in the South

Reviews

About the Author

Conclusion

Introduction

What is The Harp in the South about? This novel explores the tumultuous lives of the Darcy family in a Sydney slum during the mid-20th century. Set in the impoverished Surry Hills, the story captures the bittersweet experiences of love, loss, and resilience. Ruth Park intricately portrays the struggles of the working class while highlighting their unwavering bond and joy despite their circumstances.

Book Details

Title: The Harp in the South

Author: Ruth Park

Pages: 251

First Published: January 1, 1948

Synopsis of The Harp in the South

Setting the Scene

Set in the slums of Surry Hills, Sydney, “The Harp in the South” paints a vivid picture of poverty. Ruth Park’s deeply compassionate narrative unfolds in the 1940s, a time when the area is teeming with life and struggle. The Darcys, residing at Twelve-and-a-Half Plymouth Street, embody the resilience of the working class. They face the daily trials of life in a tenement filled with despair, love, and familial bonds. While the roads echo with laughter and the chaotic realities of slum life, the family navigates the complexities of survival in a challenging environment.

Meet the Darcys

At the heart of the story is the Darcy family. Hughie, the father, is a heavy drinker, often consumed by his own failures. Margaret, affectionately known as Mumma, tirelessly strives to hold the family together. The couple has two daughters: Roie, the eldest, is a hopeful romantic who grapples with the harsh realities of adulthood. Dolour, the younger sister, dreams of escaping their difficult life. The family’s resilience is tested through various calamities, including the disappearance of their son Thady, which casts a shadow over their lives. Their household is further complicated by the presence of boarders. Mr. Patrick Diamond, a protestant, challenges the family’s Catholic beliefs, adding to their struggles. Miss Sheily, another boarder, has a son who requires extra care, showcasing the spectrum of human relationships within their cramped quarters. Grandma Kilker’s arrival brings warmth and humor, yet also a reminder of fleeting youth and inevitable decline.

Life in a Slum

Park captures the intricacies of life in the Surry Hills slums with unflinching honesty. The narrative is replete with vivid descriptions and colorful characters, all navigating the challenges of poverty. A scene with bed bugs serves as a stark reminder of their living conditions. Park intricately portrays the community’s struggles amidst the backdrop of vibrancy, where friends gather around a bonfire, and children celebrate small moments. The harsh realities include issues like alcoholism, teenage pregnancy, and financial instability; these themes are woven together with tenderness and humor. The Darcys maintain a sense of family that serves as a beacon of hope. Their love stands firm despite facing racism, anti-Irish sentiment, and the weight of societal expectations.

First Loves and Hardships

The story intricately details Roie’s growth and her experiences with love. As Roie navigates the painful realities of first love, she faces societal pressures and personal heartbreak. This loss is underscored by her mother’s concern for the future, adding an emotional depth to their relationship. Dolour’s journey parallels Roie’s, as she grapples with her own dreams and desires. The girls’ aspirations provide a powerful counterpoint to the grimness of their surroundings. The story highlights the poignant sweetness found in mundane moments, like a trip to the beach, which becomes a joyous memory amidst their hardship.

The Heart of the Story

Despite the trials faced by the Darcys, Park captures the essence of what it means to love and endure. The family’s unity and unyielding spirit stand out, illustrating the strength that arises from togetherness. In moments of strife, there are glimpses of joy and laughter that illuminate their existence. “The Harp in the South” is more than just a narrative about poverty; it is a celebration of human resilience. The ending encapsulates the essence of their journey—Mumma’s declaration of gratitude, “I was thinking of how lucky we are,” encapsulates the profound connection they share, reminding readers that even in darkness, love can illuminate the path forward. Ruth Park’s masterful storytelling crafts a moving portrait of life in a pre-war Australian slum. This classic novel reminds readers of the strength found in familial bonds and the enduring power of hope amidst hardship. Each character’s struggles and triumphs find a space in the heart of the reader, leaving a lasting impact long after the final page is turned.

From here you can jump to the Spoilers section right away.

Below you can search for another book summary:

Search

Alternative Book Cover

Coming soon…

Quotes

“And when he got home he started on Mumma. He hated her then, because in her fatness and untidiness and drabness she reminded him of what he himself was when he was sober.”―Ruth Park,The Harp in the South

“Having a baby is different from all the ordinary ways of being hurt. it’s worth it all. Other pain isn’t worth anything, but that is.”―Ruth Park,The Harp in the South

“The announcer, in milky tones, rolled out the commercial; it was all about some sort of washing powder that made laundry days a mere frolic in the backyard”―Ruth Park,The Harp in the South

You want to give The Harp in the South a try? Here you go!

Characters

Roie Darcy: The eldest daughter, full of dreams yet grappling with early adulthood’s harsh realities. Her romantic experiences are both tender and tragic.

Mumma Darcy: The resilient matriarch, working tirelessly to provide for her family. Her love and sacrifices are a central theme in the story.

Hughie Darcy: The alcoholic father whose heavy drinking often complicates family life. His character embodies the struggles of many in his circumstances.

Dolour Darcy: Roie’s younger sister, who dreams of a better life. Her emerging teenage identity is explored throughout the narrative.

Grandma Kilker: The elderly matriarch who provides comic relief and wisdom, embodying the family’s history and traditions.

Miss Sheily: A boarder with a troubled son, representing the darker aspects of the community they live in.

Mr. Patrick Diamond: A Protestant boarder who often challenges the Catholic Darcy family, highlighting sectarian tensions.

Thady Darcy: The tragic figure, Roie and Dolour’s missing brother, whose disappearance haunts the family.

Key Takeaways

Poverty and Resilience: The story illustrates the harsh realities of poverty while celebrating the resilience of the human spirit.

Familial Love: Love within the Darcy family thrives despite the chaos, binding them together through their struggles.

Community Dynamics: The narrative explores the complexities of community life in working-class neighborhoods.

Cultural Identity: Irish heritage plays a significant role, reflecting tensions between Catholics and Protestants.

Vivid Imagery: Ruth Park’s descriptions immerse readers in the gritty details of Surry Hills, evoking strong emotions.

Spoilers

Spoiler Alert! If you want to read the book, don’t click “Show more” and spoil your experience. Here is a link for you to get the book.

Show more

FAQs about The Harp in the South

Is The Harp in the South a true story?

It’s a fictional novel, but it draws from Ruth Park’s experiences living in similar conditions.

What are the major themes of the book?

Themes include poverty, familial love, community bonds, and cultural identity.

What is the significance of the title?

The “Harp” symbolizes Irish heritage and cultural identity for the protagonists.

How does Ruth Park portray poverty?

Park depicts poverty with a mixture of honesty and compassion, showcasing both despair and resilience.

Is there a sequel to The Harp in the South?

Yes, it is part of a trilogy, followed by Poor Man’s Orange and Missus.

Reviews

For a deeper look into The Harp in the South and to explore the pros and cons, visit our full review.

Are you looking for a nice read that perfectly fits your current mood? Here is a free book suggestion tool. It gives you suggestions based on your taste. Also a likelihood rating for each recommended book. Would you like to find the book you will love later or now?

About the Author

Ruth Park was a renowned author born in New Zealand, who spent most of her life in Australia. Her experiences during the Great Depression and her keen observations of life in Surry Hills richly informed her writing.

Are you looking for a nice read that perfectly fits your current mood? Here is a free book suggestion tool. It gives you suggestions based on your taste. Also a likelihood rating for each recommended book. Would you like to find the book you will love later or now?

Conclusion

We hope you found this synopsis of The Harp in the South engaging. Summaries shine a light on the rich narratives that await in full books. If what you’ve read resonates, the complete work promises an even more profound journey. Ready for more? Here’s the link to buy The Harp in the South.

DISCLAIMER: This book summary serves as an analysis and not as a replacement for the original work. If you are the original author or rights holder of this book and wish for its removal, please contact us.

===

Community Reviews

===

The Harp in the South

Ruth Park

Fiction | Novel | Adult | Published in 1948

Plot Summary

The Harp in the South (1948), a classic Australian novel by Ruth Park, follows the Darcy family, a poor group of Irish immigrants who live in Shanty Town, or Surry Hills, a slum for Irish Catholic families living in Australia during the middle of the twentieth century. The main characters are mother, Margaret, father, Hughie, and siblings, Roie and Dolour. Together, they experience the joys and pains of life as forgotten people, forced to suffer it out on their own to make a good life for themselves.

The novel begins with the arrival of Irish Catholic settlers to Sydney, placing the family and neighborhood within a particular socioeconomic context – Park makes it clear that the ancestors of the Darcy family and their neighbors came to Shanty Town because they were poor and there was nowhere else to go. The novel centers in on the family; they live at 12 ½ Plymouth St., in a small house. Margaret, or Ruth, the matriarch of the house, is a strict and devout Catholic; her husband, Hughie, is an alcoholic who frequently drinks himself into a stupor with his best friend Patrick Diamond, despite the fact that Diamond is Protestant. Together, Ruth and Hughie raise two children, Roie and Dolour.

Early in the novel, Park reveals the tragedy that has befallen and still haunts the Darcy family. There was a middle child, Thady, who disappeared when he was six years old from the streets of Surry Hill and was never found again. The loss of a son and a brother affects all members of the family, speaking to the random tragedies and lack of justice that many poor Irish families experienced during this period in Australia history.

Park describes the secret yearnings and lives of each of the characters, including those outside the family, like Diamond and Lick Jimmy, the Chinese man who runs the market down the street from the Darcy house. Roie is a character of particular interest – a sweet, hopeful girl, she falls in love with Tommy, who has sex with her before disappearing, never to be seen again. Roie feels desperate when she realizes that she is expecting Tommy's baby; – she plans a risky abortion, which is illegal. To save money for the procedure, Roie works two jobs, but at the last minute, as she walks to the doctor's office, she decides can't go through with the operation. On her way home, she is brutally beaten by a group of soldiers, losing the baby and becoming barren. Later, she marries a sweet, indigenous man, Charlie Rothe, and learns the pleasures of married sex, finding happiness in a supportive partnership.

Other characters have similarly intriguing lives; Dolour, Roie’s younger sister, is bright and intelligent; many believe she will use her smarts to escape the slums of Surry Hill. Meeting Roie's future husband, Charlie, at a radio quiz show, she is jealous when he begins to spend all his time with Roie, taking her away from Dolour. Ruth, though ultimately accepting of Roie's new husband when she realizes how happy Roie is, is initially prejudiced against him because of his dark skin and indigenous heritage. For his part, Charlie has lived his own bizarre life – found in a remote part of the Australian bush, a swagman raised him. Critics have inferred that Charlie might be a representative of the Stolen Generation: indigenous children who were removed from their parents by the Australian parliament during the early twentieth century, to be raised by “good” English parents.

With other supplementary characters with equally deep back-stories, Park paints a portrait of the complexities and beauties of life in the inner city slums of Sydney, and particularly, the trajectory of a single Irish Catholic family.

Ruth Park is a New Zealand-born Australian author, known for her works The Harp in the South, Playing Beatie Bow, and her radio show for children called The Muddle Headed Wombat. She was married to notable author D'Arcy Niland, and won many awards for her work, including multiple Talking Book of the Year and Children's Book of the Year awards, and a Miles Franklin Award. The Harp in the South is one of the most beloved books in the Australian literary canon.

======

Amazon

==

From Australia

Donna

5.0 out of 5 stars A poignant look at early, non convict mass immigration to Australia.

Reviewed in Australia on 9 December 2023

Verified Purchase

Ruth Park has the ability to see the positive while describing the worst of people & circumstances. She draws a fine bow across the lives of the early Irish citizens of this great land.

Helpful

Report

Catherine

4.0 out of 5 stars Rather tedious to read

Reviewed in Australia on 9 September 2023

Verified Purchase

A novel about people living in straightened circumstances in Sydney in the 1930s. Tedious writing.

Helpful

Report

Cheryl

5.0 out of 5 stars Different

Reviewed in Australia on 21 February 2022

Verified Purchase

This book is very different to anything I have read of late. If you want something entertaining and has different experiences. Then read this book.

Helpful

Report

menace aforethought

5.0 out of 5 stars Classic

Reviewed in Australia on 9 February 2021

Verified Purchase

One you thought you'd read but haven't. Zings along after all these years...

Helpful

Report

David W

3.0 out of 5 stars Typeface too small

Reviewed in Australia on 17 June 2023

Verified Purchase

The story is beautifully written. Delivery was quick. But you would need a microscope to read the tiny typeface.

One person found this helpful

Helpful

Report

Alfred

5.0 out of 5 stars Harp down South.

Reviewed in Australia on 26 August 2017

Verified Purchase

A fantastic read. A sharing of time through the ages..Loved it so much. One of the best books I have ever read.

Alfred

One person found this helpful

Helpful

Report

Frank Hopkins

4.0 out of 5 stars Surry Hills in the 50's

Reviewed in Australia on 16 December 2018

Verified Purchase

The story was a good insight into the harsh way of life for the poor living in the slums of Surry Hills in the late 40's into the 50's.

One person found this helpful

Helpful

Report

Amazon Customer

5.0 out of 5 stars Good read

Reviewed in Australia on 26 March 2019

Verified Purchase

Excellent

Helpful

Report

Davey

5.0 out of 5 stars Well Written.

Reviewed in Australia on 16 January 2021

Verified Purchase

"The Harp in the South" by Ruth Park is a saga of several related generations. It is well written and very readable, the characters are unforgettable. It will stay with you for a long time.

Helpful

Report

From other countries

Glorybe

5.0 out of 5 stars Oh I absolutely LOVED this book

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 2 September 2017

Verified Purchase

Oh I absolutely LOVED this book, set in the slums of Sydney, Australia.

It tells the tale of Hugh and Margaret Darcy, how they came together and raised their children, Roie, Dolour and Thady, in abject poverty, with dirt around their feet and apathy in every bone of their bodies. But they stuck together somehow, goodness only knows how, and we hear their story.

The heartache, the cruelty and drunkeness all around, of the life in the awful slums of the big city, with a father (Hugh) that turned to the bottle whenever possible and bemoaned his fate in life.

The writing is beautiful and I was just swept away with this family. I can't wait to read the next two books in the series, to see if things change for them.

If you enjoyed Cloudstreet you will also enjoy this.

You just have to read it, soooo good!!

One person found this helpful

Report

==

From other countries

L. C. Taylor

4.0 out of 5 stars A vanished world

Reviewed in Canada on 28 November 2018

Verified Purchase

Ruth Park captures a Sydney that so many would like to forget and never should. An engrossing piece of social history.

Report

GVC

5.0 out of 5 stars Lives and Loves of Irish in Sydney

Reviewed in the United States on 24 June 2014

Verified Purchase

The Harp in the South portrays the life of a Catholic working class Irish Australian family living in the Sydney Slum suburb of Surry Hills in the first half of the 1900s. The Darcy family consists of Hughie, an unsuccessful man often drunk, his wife Margaret (Mumma), the strength of the family and their two daughters Roie and Dolour. Margaret's mother (Grandma), a bit of a wild character, comes to live with the Darcys. Also portrayed are the lives of the tenants, Orangeman Patrick Diamond and Miss Sheily, mother of an intellectually handicapped child. Their neighbour Chinese fruitier Lick Johnny also features in many chapters.

Ruth Park has been described as an Australian Charles Dickens. Many of the characters living in poverty in Sydney come to life in a way Dickens described his characters in poverty in London. The characters are credible and often universal. The inept antics of two young people (Roie and Joseph Mendel) in their first relationship are something that many of us would have memories of.

The author graphically brings Surry Hills, nearby Paddy's market and the beach suburb of Narrabeen back to life. They are very different places now. Against this background we can understand much of how the characters feel about their lives. Each character is allowed to present his or her inner thoughts and in this way the reader understands them all better. The characters like Roie and Mumma grow and develop. Many others show a caring side that we all have. The depictions of inner conflicts in the characters make them realistic. The story is warm-hearted and I left the book with the strong feeling that human relations can make life worthwhile even living in a slum.

The book was launched in Sydney when it won a literary award in Sydney Morning Herald in 1949 with some controversy. Some letter writers to the newspaper argued that the slums depicted were a fantasy and there were no slums in Sydney. Ruth Park said that the book was based on her own experiences when she moved to Surry Hills from Auckland in 1942.

The book raises a number of social issues.

* The disparity between the rich (in Rose Bay and other suburbs) and poor (Surrey Hills) in Sydney. Something that is sometimes denied.

* The role of women in a man's world.

* The influential role of the church.

3 people found this helpful

Report

David M. Birks

4.0 out of 5 stars Australian classic

Reviewed in the United States on 26 December 2012

Verified Purchase

My introduction to this wonderful novel was prompted by its high rating in a recent poll of best all- time Australian books. Ruth Park provides a captivating tale of life for a battling family in suburban Sydney. The characters are portrayed in a rich and convincing manner and the reader is soon drawn into their trials, relationships and recurring hardships. Underpinning their apparent misfortune we sense their fundamental resilience and drive to care for their loved ones.

Thoroughly recommended.

Report

GreatGran 1

5.0 out of 5 stars interesting stories

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 21 June 2019

Verified Purchase

I enjoy family histories and being based in Australia added to the variety

Report

Scot Bedford

5.0 out of 5 stars STANDS UP AGAINST TIME

Reviewed in the United States on 13 May 2011

Verified Purchase

The author's obit appeared in The Gray Lady recently. On a whim I ordered this book used for 1 cent. It was published in 1947. It is a fond reminiscence of the Irish experience in Australia. The shanty Irish provided the brute labor for the Aussie Industrial Revolution. They were poor as dirt and lived in decrepit tenenments where bed bugs sucked there blood as a nightly ritual. The flaws of this family are fondly recounted. This family is afflicted by alchoholism, poverty, and disappointment. There is a tragic loss of a young child. The daughter is are so naive she gets knocked-up and needs to visit a back alley abortionist. There is mostly grinding poverty occassionally offset by glimmers of joy or moments of happiness. This book is surprisingly readable. It is like a soap opera which opens a window on the early 20th century Irish immigrant experience in Australia. The author shows pride of craft and executes at a high level. Recommended.

One person found this helpful

Report

Barbara Davies

5.0 out of 5 stars A down to earth read about Sydney in the early 50's - about a family.

Reviewed in the United States on 11 February 2013

Verified Purchase

A truly great read, compelling , did not want to put the book down. The characters were alive and so true to life. Sad that poverty and lack of education cause hardships. This family went from disaster to disaster. The Author was clever they way she included so many topics - poverty, hardship, drinking, love of family unit, religion and hate, resilients and freindship.

One person found this helpful

Report

Alex Faber

3.0 out of 5 stars fun but drags on for quite a bit, with characters jumping in and out of the story.

Reviewed in the United States on 1 February 2014

Verified Purchase

Fun read at first. But I had to let it go because it takes so loooooooooonggggggggggggg. Every now and then I read a little bit more in it but that's not how I prefer to read a book.

Report

William Bickerton

5.0 out of 5 stars What an amazing story

Reviewed in the United States on 1 July 2013

Verified Purchase

This is an amazing story that tells it the way it really was in the early days of last century in old Sydney town.

Extremely well written and the use of the slang of the day is authentic and well understood.

I could not put it down and was disappointed when i finished the book - I wanted more of the same.

One person found this helpful

Report

Brian Lynne

4.0 out of 5 stars Interesting

Reviewed in the United States on 2 July 2013

Verified Purchase

The book is in two parts and seems to me as if there is a chunk missing from the middle.

This is an interesting expose of life in poorer areas of Sydney last century. The characters are real and the scenes vividly described.

It possibly drags on a bit long but worth the read.

One person found this helpful

Report

half century

5.0 out of 5 stars An Australia Great worthy of reading

Reviewed in the United States on 7 April 2013

Verified Purchase

This has been ranked in the top 10 of Australian novels. I realised I had not

read and thought - better read. Fantastic and so happy that I read. It is a long book but

never boring. If you are Australian, of a certain age, I am sure that you would have had aunties or uncles or

known of someone that had grown up in these circumstances.

One person found this helpful

Report

==

From other countries

Savannah

5.0 out of 5 stars An Australian Heritage

Reviewed in the United States on 7 December 2012

Verified Purchase

For anyone planning to visit or planning to relocate to Australia this is a must read. Yes it is set in the past, however the insights it provides on how the Australian character has been shaped through migration and distance are both revealing and honest. The story is told through the eyes of a poor family living in Sydney. Despite the onset of time and the changes to living conditions the complete characters created here can be found everywhere. For Americans it helps provide an answer to the Australian attitude to success and self promotion often referred to as 'The Tall Poppy Syndrome'. Times may have changed but the people have not.

Report

cutex

5.0 out of 5 stars unforgettable

Reviewed in the United States on 24 September 2013

Verified Purchase

What could have been viewed as a tragic & depressing story was not, although the Darcy family live in abject poverty & dysfunction, they have a wealth of family love. The characters, sinners & saintlike, warm the heart as they endure the many disappointments visited upon them. A truly wonderful story that does not sugar coat or romanticise, yet leaves a lasting impression of the slum area & it's inhabitants of Surry Hills.

,

One person found this helpful

Report

red

5.0 out of 5 stars Ruth Park is brilliant

Reviewed in the United States on 5 June 2013

Verified Purchase

What a delicious story of Australia and its' people. This is a story of the harsh outback and the harsh way of life. Could not put this novel down, love reading historical stories of our past and have only admiration for our ancestors. They worked hard and played hard and times were very tough indeed. Great read

One person found this helpful

Report

Jo Paul-Taylor

4.0 out of 5 stars Fabulous

Reviewed in the United States on 7 February 2013

Verified Purchase

Can't believe it took me so long to read this. The evocation of Surry Hills was particularly fascinating to me as an ex-resident of the area but it is the characters that really drive this novel.

Report

Diana Mepsted

4.0 out of 5 stars History with realism.

Reviewed in the United States on 3 November 2013

Verified Purchase

A good look at life of the era. Really puts the reader in the picture and presents history with good story. Great for Australian readers familiar with the area then, and now. .

Report

Maureen Quain

5.0 out of 5 stars Touching but Funny

Reviewed in the United States on 25 April 2013

Verified Purchase

Harp In The South Trilogy is an easy read giving an insight into the early Irish Catholic life in Sydney.

A hard life for many but filled with love and support and a funny sense of humour.

The daily hard life of many of these early settlers in Australia is bought to life in the pages of these books.

Report

Sue P

4.0 out of 5 stars Aussie classic

Reviewed in the United States on 22 April 2015

Verified Purchase

I loved the descriptive language used. You could almost smell the poverty of Surry Hills.

A great read don't put it off any longer.

One person found this helpful

Report

bellarosi

5.0 out of 5 stars The Harp in the South

Reviewed in the United States on 12 January 2013

Verified Purchase

I heard about Ruth Park and the harp in the south, I wanted to read the book because of being anAustralian author and also set in Australia, fabulous you could place yourself back in time, almost like a fly on the wall. Not somewhere or away I could live but understand how some would and did

Report

parisolivia1

5.0 out of 5 stars I even bought the DVD's!

Reviewed in the United States on 27 June 2013

Verified Purchase

I loved this beautifully written Australian novel. So much so that when I had finished I purchased the DVD so I could see it in the flesh (which is never the same of course). In particular I loved "Mumma's" character and just wanted to reach in and take her to a better place.

One person found this helpful

Report

Rob bullen.

5.0 out of 5 stars Fantastic read ...

Reviewed in the United States on 10 November 2018

Verified Purchase

Very entertaining read

.. putting into perspective early 20th century Australian life, the cost and trap of poverty for all the family, the power of love and the impact of life's simple choices and opportunities.

Report

==

From other countries

Louise Marriott

5.0 out of 5 stars Brilliant

Reviewed in the United States on 11 January 2013

Verified Purchase

An amazing, wonderful and extremely well written book. I have no idea how thick it is in hardcopy but I could not put it down and had to keep reading it all hours. The fabulous characters were brought alive providing great insights into the lives of these immigrants around Sydney in that era .

Report

Tina M

5.0 out of 5 stars Don't miss this book. It's a must read!

Reviewed in the United States on 23 June 2013

Verified Purchase

This book had a huge impact on me. One of the best books I have ever read. A true history of the early days of Australia; the trials of women to survive in a man's world. The restrictions placed on life by the church - it's got it all!

One person found this helpful

Report

susan boyke

5.0 out of 5 stars An Australian classic

Reviewed in the United States on 12 January 2013

Verified Purchase

If you enjoy experiencing an historical era as if it's so real with real characters that you can relate to, then you will love this one. It would have to be in the top ten best Australian books of all time. You will shed a few tears but it's worth it.

Report

Jon Snyder

4.0 out of 5 stars A classic

Reviewed in the United States on 14 April 2013

Verified Purchase

Conveys extremely well what life could be like for poor peaople with minimal education and life opportunities, living in the slums of Sydney.

Report

Tammy

4.0 out of 5 stars Well worth reading!

Reviewed in the United States on 20 July 2013

Verified Purchase

A poignant summary of the human condition. So many recognisable characters to anyone who has lived in or observed Australian suburbia.

Report

sallyj

5.0 out of 5 stars Feels like you're in the story

Reviewed in the United States on 30 March 2013

Verified Purchase

Ruth Parks'novel is written in such vivid detail, that even though it was written in a completely different era, you feel as if you're right there seeing the events taking place. the characters are mostly flawed but totally reachable and believable. Its a great read.

Report

Amazon Customer

5.0 out of 5 stars you must read this

Reviewed in the United States on 3 June 2013

Verified Purchase

Spellbinding. Dont want to put it down. At times overwhelming by the depth of poverty and the hopelessness

of ever overcoming it but such an insight into the enduring nature of love and the simple pleasures of life.

Report

Glennis Norris

5.0 out of 5 stars Excellent read

Reviewed in the United States on 27 April 2014

Verified Purchase

Thoroughly enjoyed this book, especially the wonderfully descriptive writing. I was swept along with the story and was quite disappointed when it came to a close. It left me wanting more!

2 people found this helpful

Report

pat

5.0 out of 5 stars Harp in The South

Reviewed in the United States on 26 December 2012

Verified Purchase

real

Australian historical setting which is not artificial with real, credible characters a,situations and lifestyles.I read this because it was on the best book list of australian authors. An oldie but a goodie.

Report

David Pearson

5.0 out of 5 stars Brilliant

Reviewed in the United States on 23 June 2014

Verified Purchase

Brilliant expose of lifes journey thru transgenerational eyes of the melting pot that produced the archetypal " Aussie Battler " .

A masterpiece of nostalgia not so far removed.

Report

============================

No comments:

Post a Comment