Promise at Dawn

READER RATING

AUTHOR: ROMAIN GARY

CATEGORY: BIOGRAPHY & TRUE STORIES , CLASSIC FICTION (PRE C 1945) , FICTION: SPECIAL FEATURES

BOOK FORMAT: PAPERBACK / SOFTBACK

PUBLISHER: PENGUIN

ISBN: 9780241347638

RRP: $22.99

FIND A BOOKSHOP (AU)

FIND A BOOKSHOP (NZ)

FIND A LIBRARY NEAR YOU

Synopsis

A romantic, thrilling memoir that has become a French classic

‘You will be a great hero, a general, Gabriele d’Annunzio, Ambassador of France!’

For his whole life, Romain Gary’s fierce, eccentric mother had only one aim- to make her son a great man. And she did. This, his thrilling, wildly romantic autobiography, is the story of his journey from poverty in Eastern Europe to the sensual world of the C te d’Azur and on to wartime pilot, resistance hero, diplomat, filmmaker, star and one of the most famed French writers of his age.

Romain Gary was one of the most important French writers of the 20th century. He won the once-in-a-lifetime honour the Prix Goncourt twice, the only person ever to have done so, by writing under a secret nom de plume. He was married to the American actress Jean Seberg and served in the RAF during the Second World War. He died in Paris in 1980 from a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

로맹 가리의 자전적 스토리, 영화 ‘새벽의 약속’

박차영 기자

승인 2021.04.01

공쿠르상을 두 번 수상한 유일한 작가…어머니에게 바치는 영화

넷플릭스의 영화 ‘새벽의 약속’(2017)은 프랑스 작가 로맹 가리(Romain Gary, 1914~1980)의 자전적 소설(La Promesse de l'aube)을 토대로 했다. 영화는 소설이 출간된 1960년 이전의 스토리로 끝을 맺는다. 로맹 가리는 그로부터 20년을 더 살아 1980년 66세의 나이로 자살한다.

로맹 가리는 프랑스 최고 문학상인 공쿠르상(Prix Goncourt)을 두 번 탄 유일한 작가다.

그의 본명은 로망 카제프(Roman Kacew)인데, 2차 대전이 끝난후 이름을 로맹 가리로 바꾸었다. 1956년, 로맹 가리라는 본명으로 쓴 ‘하늘의 뿌리’로 공쿠르 문학상을 받았고, 1975년에 에밀 아자르(Émile Ajar)라는 가명으로 쓴 ‘자기 앞의 생’을 발표, 두 번째 공쿠르상을 수상했다. 공쿠르상은 작가 1인에게 한번 주는 게 관례였는데, 가명으로 썼기 때문에 두 번 탄 것이다. 그는 유언에서 에밀 아자르가 자신임을 밝혔다.

영화는 크게 세 부분으로 나눠진다. 첫 번째는 당시 러시아제국에 속했던 리투아니아의 빌뉴스에서의 어린 시절, 두 번째는 프랑스 니스로 이사한 후의 생활, 세 번째는 2차 대전 기간의 일화다.

영화를 관통하는 것은 어머니 니나 카제프(Nina Kacew)의 아들에 대한 천착이다. 로맹은 어머니의 뜻에 따라 법대에 진학하고, 작가를 시작하고, 전쟁에 참가한다. 어머니의 극성은 때론 그에게 힘이 되지만, 때론 반항을 불러 일으킨다.

사관생도 300명 중에 유대인이라는 이유로 유일하게 장교가 되지 못한 일, 2차 대전에 공중전에서 용맹을 떨친 일들은 그의 일대기에 유명한 일화다.

영화에서 가장 가슴 아프게 한 대목은 로맹이 전쟁터에서 부상을 입어 입원해 있을 때에도 어머니의 편지가 온다. 그러나 어머니는 죽어 있었다. 그는 전쟁이 끝난후 집에 돌아갔을 때 이미 어머니는 3년전에 죽었다는 소식을 들었다. 어머니가 이모에게 매주 편지를 보내라고 250통이나 미리 써 놓았다는 것이다.

로맹 가리의 어머니는 유대인 어머니의 극성을 보여준다. 그는 어머니의 뜻대로 작가가 되었고, 외교관이 되었고, 여배우와 결혼했다. 그러나 어머니의 죽음을 안 순간부터 그는 삶에 대한 목표와 희망을 잃어버린다.

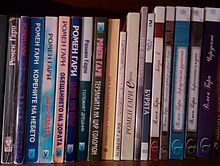

로맹 가리는 가명으로 쓴 것까지 포함해 30권 이상의 소설과 에세이, 회고록을 쓴 프랑스의 대중적 작가다.

그는 두 번 결혼했다. 첫 번째는 영국 작가이자 보그지의 편집장인 레슬리 블랜치와 결혼했다 이혼하고, 미국 헐리웃 여배우 잔 세버그(Jean Seberg)와 재혼했다. 세버그는 FBI의 공작요원으로 활동한 것으로 알려졌는데, 나이 40살이던 1979년 자결했다. 두 번째 아내인 세버그는 헐리웃 스타 클린트 이스트우드와 관계를 맺었는데, 로맹 가리가 이스트우드에게 결투를 신청했다고 한다.

로맹 가리는 1980년 12월에 권총자살을 했다. 그는 유언에서 에밀 아자르가 본인임을 밝히면서, 아내 때문에 자살한 것이 아니라고 주장했다.

==

Promise at Dawn (novel)

First UK edition (publ. Michael Joseph) | |

| Author | Romain Gary |

|---|---|

| Original title | La promesse de l'aube |

| Translator | John Markham Beach |

| Language | French |

| Publisher | Éditions Gallimard |

Publication date | 1960 |

| Publication place | France |

Published in English | 1961 |

| Pages | 374 |

Promise at Dawn (French: La promesse de l'aube) is a 1960 autobiographical novel by the French writer Romain Gary.

Summary[edit]

Romain Gary tells the story of his childhood and youth with his mother, a Russian former actress carried by a love and unconditional faith in her son. The story, full of humor and tenderness, tells the story of her tireless battle against adversity, the extravagant energy she deploys so that he attain to a great destiny, and the efforts of Romain, who is willing to do all to make his life coincide "with the naive dream of the one he loves".

The first part begins with the reveries of a mature Romain, remembering how, out of love for his mother, he had decided to stand against the stupidity and meanness of the world. It then relates his childhood years in the Polish city of Wilno (now Vilnius). Romain's mother instills in him his dreams of triumph: he will be a great man, admired and adulated, a great persuader, a great artist. They will go to France, a country she adorns with all virtues. During a brief period of prosperity, due to the success of a "Parisian haute couture" shop energetically run by his mother, he leads an extravagant lifestyle with a whole host of tutors. His mother pushes him, without success, into various artistic activities, and he does his best to discover his talents. He begins to write (or more precisely to look for pseudonyms evoking his future glory). He tells how he later become what his mother had predicted — a famous writer, a war hero while relating the penniless period that followed their arrival in Wilno. His mother, to his horror, would announce his ambitions to the neighbors, and was duly showered with jibes. The failure of the fashion house brings them back to hard times. They move to Warsaw, "temporarily", awaiting their move to what they consider their "real" country, France. A humiliation at school - he did not react whereas his mother was called "cocotte" - leads to the decision to move to Nice.

In the second part, the narrator refers to his adolescence in Nice. Romain's mother, despite her energy in the face of adversity, is forced to ask for help - we imagine that she turns to the father of Romain. Romain devotes himself to writing, in order to attain the expected fame. He also makes his first experiences as a man, making his mother proud. She at last finds stability by becoming manager of the Hotel-Pension Mermonts. Life becomes happy. And yet, Romain is plagued by the worry that he will not succeed in time to offer his victory to his mother, when he learns that she has diabetes, a fact she had been hiding from him for two years. Old and sick, she continues to fight forcefully and to convey to her son her certainty of a bright future for him. He moves to Aix-en-Provence, then to Paris to get a law degree, and in 1938 becomes an officer cadet at the air school of Salon-de-Provence. But he is not promoted, because he has only recently become a French citizen, and he invents a lie to avoid giving his mother too painful a disappointment. When the war breaks out, he goes as a simple corporal. He sees her again in 1940 on leave, and when he leaves her she is very unwell.

The third part covers the war years, during which he receives from his mother countless letters of encouragement and exhortations to valor. Having joined the Free French Air Forces, he fights in Great Britain and Africa and ends the war with the rank of captain. He is made Compagnon de la Libération and officer of the Legion d'Honneur. He publishes Éducation européenne in 1945 in England, which gets a favorable reception, and he is given the opportunity to enter the diplomatic service for "exceptional services". Returning to Nice at the end of the war, he discovers that his mother has died three and a half years earlier, having given a friend the task of sending her son hundreds of letters that she had written for him in the days preceding her death.

Adaptations[edit]

Samuel Taylor adapted the novel into a three-act play named First Love (New York opening: 25 Dec 1961).

Two films based on the novel, and sharing the same title, have been released: Promise at Dawn (1970) directed by Jules Dassin,[1] and Promise at Dawn (2017) directed by Éric Barbier.[2]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Kanfer, Stefan (1971-02-08). "Cinema: Smotherhood". Time. Archived from the original on December 21, 2008. Retrieved 2012-01-01.

- ^ Lodge, Guy (16 October 2017). "Film Review: 'Promise at Dawn'". Variety. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

Promise at Dawn (2017 film)

| Promise at Dawn | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| French | La Promesse de l'aube |

| Directed by | Éric Barbier |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Promise at Dawn by Romain Gary |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Glynn Speeckaert[1] |

| Edited by | Jennifer Augé[1] |

| Music by | Renaud Barbier[2] |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 131 minutes[3] |

| Countries |

|

| Budget | €18–24.4 million[4][5] |

| Box office | $9.2 million[6] |

Promise at Dawn (French: La Promesse de l'aube) is a 2017 drama film directed by Éric Barbier, from a screenplay written by Barbier and Marie Eynard. It is the second screen adaptation of Romain Gary's 1960 autobiographical novel Promise at Dawn, following Jules Dassin's 1970 version.[1] The film is a co-production between France and Belgium. It stars Pierre Niney and Charlotte Gainsbourg. It had its world premiere at the 22nd Busan International Film Festival on 14 October 2017. It was released in France and Belgium on 20 December 2017.

Premise[edit]

Roman Kacew recounts his life, from his childhood through his service in World War II, and the story of his self-sacrificing mother Nina, who raised him alone.

Cast[edit]

- Pierre Niney as Roman Kacew

- Pawel Puchalski as Roman Kacew, ages 8–10

- Nemo Schiffman as Roman Kacew, ages 14–16

- Charlotte Gainsbourg as Nina Kacew

- Didier Bourdon as Alex Gubernatis

- Jean-Pierre Darroussin as Zaremba

- Catherine McCormack as Lesley Blanch

- Finnegan Oldfield as Arnaud Langer

- Pascal Gruselle as Colonel Salon

- Alexandre Picot Sergeant Dufour

- Michel Schillaci as Intendant

Production[edit]

The film was produced by Éric Jehelmann and Philippe Rousselet for Jerico Films, in co-production with Pathé Films, TF1 Films Production, Lorette Cinéma and Belgium's Nexus Factory and Umedia.[1]

Release[edit]

Promise at Dawn was first screened in a sneak preview at the Pathé cinema in Évreux, Normandy, in the presence of Éric Barbier.[7] The film was selected to be screened in the World Cinema section at the 22nd Busan International Film Festival.[8][9] It had its world premiere in Busan on 14 October 2017.[10] It was theatrically released in France by Pathé Distribution on 20 December 2017.[11] It was released the same day in Belgium by Alternative Films.

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

On its first day, Promise at Dawn sold 46,358 admissions in France.[12] At the end of its theatrical run in France, the film sold a total of 1,053,288 admissions, grossing a domestic total of $8.8 million[5] and a worldwide total of $9.2 million.[6]

Critical response[edit]

Promise at Dawn received an average rating of 3.3 out of 5 stars on the French website AlloCiné, based on 30 reviews.[13] On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 64% based on 11 reviews, with an average rating of 6.4/10.[14]

Ben Kenigsberg of The New York Times wrote, "The movie looks and sounds great, but greatness and depth elude it".[15]

Accolades[edit]

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| César Awards | 2 March 2018 | Best Actress | Charlotte Gainsbourg | Nominated | [16] |

| Best Adaptation | Éric Barbier and Marie Eynard | Nominated | |||

| Best Production Design | Pierre Renson | Nominated | |||

| Best Costume Design | Catherine Bouchard | Nominated | |||

| Lumières Award | 5 February 2018 | Best Actress | Charlotte Gainsbourg | Nominated | [17] |

| Sarlat Film Festival | 18 November 2017 | Prix des lycéens | Promise at Dawn | Won | [18][19] |

| Prix d'interprétation masculine | Pierre Niney | Won |

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Lodge, Guy (16 October 2017). "Film Review: 'Promise at Dawn'". Variety. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Jihelbey (28 April 2018). "La Promesse de l'aube : une adaptation grandiose (en Blu-ray, DVD et VOD)". ON-mag.fr (in French). Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Fagerholm, Matt (6 September 2019). "Promise at Dawn movie review & film summary (2019)". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Aubel, François (23 August 2016). "Sur le tournage de La Promesse de l'aube, avec Pierre Niney et Charlotte Gainsbourg". Le Figaro (in French). Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ a b "La Promesse de l'aube". JP Box Office (in French). Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ a b "Promise at Dawn (2017)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Rol, Catherine (21 August 2017). "Eure: une semaine de cinéma à 4€ la séance". Paris-Normandie (in French). Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ González, David (12 October 2017). "A strong European contingent gets ready to head to Busan". Cineuropa. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ "French films at the 22nd Busan International Film Festival". Unifrance. 4 October 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ "Promise at Dawn". Busan International Film Festival. September 2017. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ "A Ghost story, La promesse de l'aube, Ferdinand : les films au cinéma cette semaine". Première (in French). 20 December 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Champalaune, Mathieu (21 December 2017). "Box office: Ferdinand démarre bien, Star Wars continue à tout écraser". Les Inrockuptibles (in French). Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Critiques Presse pour le film La Promesse de l'aube". AlloCiné (in French). Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- ^ "Promise at Dawn". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Kenigsberg, Ben (5 September 2019). "'Promise at Dawn' Review: An Extraordinary Life, Thanks to Mom". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (31 January 2018). "César Nominations: 'BPM', 'Au Revoir Là-Haut' Lead Hunt For Top French Film Prizes". Deadline. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Keslassy, Elsa (11 December 2017). "Robin Campillo's 'BPM (Beats Per Minute)' Leads France's 2017 Lumieres Nominations". Variety. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Bellet, Nicolas (18 November 2017). "Festival du Film de Sarlat 2017 : le palmarès vient de tomber". Première (in French). Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "2017, 26ème édition". Festival du Film de Sarlat (in French). Retrieved 25 March 2023.

External links[edit]

Romain Gary

Romain Gary | |

|---|---|

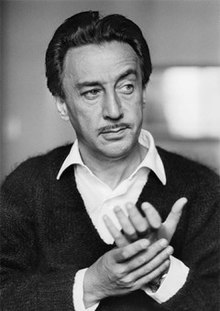

Gary in 1961 | |

| Born | Roman Kacew[1] 21 May 1914 Vilnius, Vilna Governorate, Lithuania |

| Died | 2 December 1980 (aged 66) Paris, France |

| Pen name | Romain Gary, Émile Ajar, Fosco Sinibaldi, Shatan Bogat |

| Occupation | Diplomat, pilot, writer |

| Language | French, English, Polish, Russian, Yidish |

| Nationality | French |

| Citizenship | Russian Empire and Republic of Poland / France (since 1935) |

| Education | Law |

| Alma mater | Faculté de droit d'Aix-en-Provence Paris Law Faculty |

| Period | 1945–1979 |

| Genre | Novel |

| Notable works | Les racines du ciel La vie devant soi |

| Notable awards | Prix Goncourt (1956 and 1975) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 1 |

Romain Gary (pronounced [ʁɔ.mɛ̃ ga.ʁi]; 21 May [O.S. 8 May] 1914 – 2 December 1980), born Roman Kacew (pronounced [kat͡sɛf], and also known by the pen name Émile Ajar), was a French novelist, diplomat, film director, and World War II aviator. He is the only author to have won the Prix Goncourt under two names. He is considered a major writer of French literature of the second half of the 20th century. He was married to Lesley Blanch, then Jean Seberg.

Early life[edit]

Gary was born Roman Kacew (Yiddish: רומן קצב Roman Katsev, Russian: Рома́н Ле́йбович Ка́цев, Roman Leibovich Katsev) in Vilnius (at that time in the Russian Empire).[1][2] In his books and interviews, he presented many different versions of his parents' origins, ancestry, occupation and his own childhood. His mother, Mina Owczyńska (1879—1941),[1][3] was a Jewish actress from Švenčionys (Svintsyán) and his father was a businessman named Arieh-Leib Kacew (1883—1942) from Trakai (Trok), also a Lithuanian Jew.[4][5] The couple divorced in 1925 and Arieh-Leib remarried. Gary later claimed that his actual father was the celebrated actor and film star Ivan Mosjoukine, with whom his actress mother had worked and to whom he bore a striking resemblance. Mosjoukine appears in his memoir Promise at Dawn.[6] Deported to central Russia in 1915, they stayed in Moscow until 1920.[7] They later returned to Vilnius, then moved on to Warsaw. When Gary was fourteen, he and his mother emigrated illegally to Nice, France.[8] Gary studied law, first in Aix-en-Provence and then in Paris. He learned to pilot an aircraft in the French Air Force in Salon-de-Provence and in Avord Air Base, near Bourges.[9]

Career[edit]

Despite completing all parts of his course successfully, Gary was the only one of almost 300 cadets in his class not to be commissioned as an officer. He believed the military establishment was distrustful of him because he was a foreigner and a Jew.[8] Training on Potez 25 and Goëland Léo-20 aircraft, and with 250 hours flying time, only after three months' delay was he made a sergeant on 1 February 1940. Lightly wounded on 13 June 1940 in a Bloch MB.210, he was disappointed with the armistice; after hearing General de Gaulle's radio appeal, he decided to go to England.[8] After failed attempts, he flew to Algiers from Saint-Laurent-de-la-Salanque in a Potez. Made adjutant upon joining the Free French and serving on Bristol Blenheims, he saw action across Africa and was promoted to second lieutenant. He returned to England to train on Boston IIIs. On 25 January 1944, his pilot was blinded, albeit temporarily, and Gary talked him to the bombing target and back home, the third landing being successful. This and the subsequent BBC interview and Evening Standard newspaper article were an important part of his career.[8] He finished the war as a captain in the London offices of the Free French Air Forces. As a bombardier-observer in the Groupe de bombardement Lorraine (No. 342 Squadron RAF), he took part in over 25 successful sorties, logging over 65 hours of air time.[10] During this time, he changed his name to Romain Gary. He was decorated for his bravery in the war, receiving many medals and honours, including Compagnon de la Libération and commander of the Légion d'honneur. In 1945 he published his first novel, Éducation européenne. Immediately following his service in the war, he worked in the French diplomatic service in Bulgaria and Switzerland.[11] In 1952 he became the secretary of the French Delegation to the United Nations.[11] In 1956, he became Consul General in Los Angeles and became acquainted with Hollywood.[11]

As Émile Ajar[edit]

In a memoir published in 1981, Gary's nephew Paul Pavlowitch claimed that Gary also produced several works under the pseudonym Émile Ajar. Gary recruited Pavlowitch to portray Ajar in public appearances, allowing Gary to remain unknown as the true producer of the Ajar works, and thus enabling him to win the 1975 Goncourt Prize, a second win in violation of the prize's usual rules.[12]

Gary also published under the pseudonyms Shatan Bogat and Fosco Sinibaldi.[12]

Literary work[edit]

Gary became one of France's most popular and prolific writers, writing more than 30 novels, essays and memoirs, some of which he wrote under a pseudonym.

He is the only person to win the Prix Goncourt twice. This prize for French language literature is awarded only once to an author. Gary, who had already received the prize in 1956 for Les racines du ciel, published La vie devant soi under the pseudonym Émile Ajar in 1975. The Académie Goncourt awarded the prize to the author of that book without knowing his identity. Gary's cousin's son Paul Pavlowitch posed as the author for a time. Gary later revealed the truth in his posthumous book Vie et mort d'Émile Ajar.[13] Gary also published as Shatan Bogat, René Deville and Fosco Sinibaldi, as well under his birth name Roman Kacew.[14][15]

In addition to his success as a novelist, he wrote the screenplay for the motion picture The Longest Day and co-wrote and directed the film Kill! (1971),[16] which starred his wife at the time, Jean Seberg. In 1979, he was a member of the jury at the 29th Berlin International Film Festival.[17]

Diplomatic career[edit]

After the end of the hostilities, Gary began a career as a diplomat in the service of France, in consideration of his contribution to the liberation of the country. In this capacity, he held positions in Bulgaria (1946–1947), Paris (1948–1949), Switzerland (1950–1951), New York (1951–1954) — at the Permanent Mission of France to the United Nations, where he regularly rubbed shoulders with the Jesuit Teilhard de Chardin, whose personality deeply marked him and inspired him, particularly for the character of Father Tassin in Les Racines du ciel—in London (1955), then as Consul General of France in Los Angeles (1956–1960). Back in Paris, he remained unassigned until he was laid off from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1961).

Personal life and final years[edit]

Gary's first wife was the British writer, journalist, and Vogue editor Lesley Blanch, author of The Wilder Shores of Love. They married in 1944 and divorced in 1961. From 1962 to 1970, Gary was married to American actress Jean Seberg, with whom he had a son, Alexandre Diego Gary. According to Diego Gary, he was a distant presence as a father: "Even when he was around, my father wasn't there. Obsessed with his work, he used to greet me, but he was elsewhere."[18]

After learning that Jean Seberg had had an affair with Clint Eastwood, Gary challenged him to a duel, but Eastwood declined.[19]

Gary died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound on 2 December 1980 in Paris. He left a note which said that his death had no relation to Seberg's suicide the previous year. He also stated in his note that he was Émile Ajar.[20]

Gary was cremated in Père Lachaise Cemetery and his ashes were scattered in the Mediterranean Sea near Roquebrune-Cap-Martin.[21]

Legacy[edit]

The name of Romain Gary was given to a promotion of the École nationale d'administration (2003–2005), the Institut d'études politiques de Lille (2013), the Institut régional d'administration de Lille (2021–2022) and the Institut d'études politiques de Strasbourg (2001–2002), in 2006 at Place Romain-Gary in the 15th arrondissement of Paris and at the Nice Heritage Library. The French Institute in Jerusalem also bears the name of Romain Gary.

On 16 May 2019, his work appeared in two volumes in the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade under the direction of Mireille Sacotte.

In 2007, a statue of Romualdas Kvintas, «The Boy with a Galoche», was unveiled, depicting the 9-year-old little hero of the Promise of Dawn, preparing to eat a shoe to seduce his little neighbor, Valentina. It is placed in Vilnius, in front of the Basanavičius, where the novelist lived.

A plaque to his name is affixed in the Pouillon building of the Faculty of Law and Political Science of Aix-Marseille where he studied.

In 2022, Denis Ménochet portrayed Gary in White Dog (Chien blanc), a film adaptation by Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette of Gary's 1970 book.[22]

Bibliography[edit]

As Romain Gary[edit]

- French: Éducation européenne (1945); translated as Forest of Anger

- French: Tulipe (1946); republished and modified in 1970.

- Le Grand Vestiaire (1949); translated as The Company of Men (1950)

- Les Couleurs du jour (1952); translated as The Colors of the Day (1953); filmed as The Man Who Understood Women (1959)

- Les Racines du ciel — 1956 Prix Goncourt; translated as The Roots of Heaven (1957); filmed as The Roots of Heaven (1958)

- Lady L (1958); self-translated and published in French in 1963; filmed as Lady L (1965)

- La Promesse de l'aube (1960); translated as Promise at Dawn (1961); filmed as Promise at Dawn (1970) and Promise at Dawn (2017)

- Johnie Cœur (1961, a theatre adaptation of "L'homme à la colombe")

- Gloire à nos illustres pionniers (1962, short stories); translated as "Hissing Tales" (1964)

- The Ski Bum (1965); self-translated into French as Adieu Gary Cooper (1969)

- Pour Sganarelle (1965, literary essay)

- Les Mangeurs d'étoiles (1966); self-translated into French and first published (in English) as The Talent Scout (1961)

- La Danse de Gengis Cohn (1967); self-translated into English as The Dance of Genghis Cohn

- La Tête coupable (1968); translated as The Guilty Head (1969)

- Chien blanc (1970); self-translated as White Dog (1970); filmed as White Dog (1982)

- Les Trésors de la mer Rouge (1971)

- Europa (1972); translated in English in 1978.

- The Gasp (1973); self-translated into French as Charge d'âme (1978)

- Les Enchanteurs (1973); translated as The Enchanters (1975)

- La nuit sera calme (1974, interview)

- Au-delà de cette limite votre ticket n'est plus valable (1975); translated as Your Ticket Is No Longer Valid (1977); filmed as Your Ticket Is No Longer Valid (1981)

- Clair de femme (1977); filmed as Womanlight (1979)

- La Bonne Moitié (1979, play)

- Les Clowns lyriques (1979); new version of the 1952 novel, Les Couleurs du jour (The Colors of the Day)

- Les Cerfs-volants (1980); translated as The Kites (2017)

- Vie et Mort d'Émile Ajar (1981, posthumous)

- L'Homme à la colombe (1984, definitive posthumous version)

- L'Affaire homme (2005, articles and interviews)

- L'Orage (2005, short stories and unfinished novels)

- Un humaniste, short story

As Émile Ajar[edit]

- Gros câlin (1974); illustrated by Jean-Michel Folon, filmed as Gros câlin (1979)

- La vie devant soi — 1975 Prix Goncourt; filmed as Madame Rosa (1977); translated as "Momo" (1978); re-released as The Life Before Us (1986). Filmed as The Life Ahead (2020)

- Pseudo (1976)

- L'Angoisse du roi Salomon (1979); translated as King Solomon (1983).

- Gros câlin – new version including final chapter of the original and never published version.

As Fosco Sinibaldi[edit]

- L'homme à la colombe (1958)

As Shatan Bogat[edit]

- Les têtes de Stéphanie (1974)

Filmography[edit]

As screenwriter[edit]

- 1958: The Roots of Heaven

- 1962: The Longest Day

- 1978: La vie devant soi

As actor[edit]

- 1936: Nitchevo – Le jeune homme au bastingage

- 1967: The Road to Corinth – (uncredited) (final film role)

As director[edit]

- 1968: Birds in Peru (Birds in Peru) starring Jean Seberg

- 1971: Kill! Kill! Kill! Kill! also starring Jean Seberg

In popular culture[edit]

- 2019: Seberg , joué par Yvan Attal

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Ivry, Benjamin (21 January 2011). "A Chameleon on Show". Daily Forward.

- ^ Romain Gary et la Lituanie Archived 26 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Myriam Anissimov. Romain Gary, le Caméléon. Paris: Les éditions Folio Gallimard, 2004. ISBN 978-2-207-24835-5, pp. ??

- ^ "Romain Gary". Encyclopédie sur la mort. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ Schoolcraft, Ralph W. (2002). Romain Gary: the man who sold his shadow. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 165. ISBN 0-8122-3646-7.

- ^ Schwartz, Madeleine. "Romain Gary: A Short Biography". The Harvard Advocate.

- ^ Passports of mother Mina Kacew and nurse-maid Aniela Voiciechowics. See Lithuaninan Central State Archives, F. 53, 122, 5351 and F. 15, 2, 1230. Copies of the documents are in the personal archive of a Moscow historian Alexander Vasin.

- ^ a b c d Marzorati 2018

- ^ "Romain Gary: The greatest literary conman ever?".

- ^ "Ordre de la Libération". Archived from the original on 26 November 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ a b c Bellos, David (2010). Romain Gary: A Tall Story. pp. ??.

- ^ a b Prial, Frank J. (2 July 1981). "Gary won '75 Goncourt under Pseudonym 'Ajar'". The New York Times.

- ^ Gary, Romain, Vie et mort d'Émile Ajar, Gallimard – NRF (17 juillet 1981), 42p, ISBN 978-2-07-026351-6.

- ^ Lushenkova, Anna (2008). "La réinvention de l'homme par l'art et le rire: 'Les Enchanteurs' de Romain Gary". In Clément, Murielle Lucie (ed.). Écrivains franco-russes. Faux titre. Vol. 318. Rodopi. pp. 141–163. ISBN 978-90-420-2426-7.

- ^ Di Folco, Philippe (2006). Les grandes impostures littéraires: canulars, escroqueries, supercheries, et autres mystifications. Écriture. pp. 111–113. ISBN 2-909240-70-3.

- ^ "Romain Gary". IMDb. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ "Berlinale 1979: Juries". berlinale.de. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ^ Paris Match No.3136

- ^ Bellos, David (12 November 2010). "Romain Gary: au revoir et merci". The Telegraph. UK.

- ^ D. Bona, Romain Gary, Paris, Mercure de France-Lacombe, 1987, p. 397–398.

- ^ Beyern, B., Guide des tombes d'hommes célèbres, Le Cherche Midi, 2008, ISBN 978-2-7491-1350-0

- ^ Demers, Maxime (2 November 2022). "«Chien blanc»: le goût du risque d'Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette". Le Journal de Montréal. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

Further reading[edit]

- Ajar, Émile (Romain Gary), Hocus Bogus, Yale University Press, 2010, 224p, ISBN 978-0-300-14976-0 (translation of Pseudo by David Bellos, includes The Life and Death of Émile Ajar)

- Anissimov, Myriam, Romain Gary, le caméléon (Denoël 2004)

- Bellos, David, Romain Gary: A Tall Story, Harvill Secker, 2010, 528p, ISBN 978-1-84343-170-1

- Bellos, David. 2009. The cosmopolitanism of Romain Gary. Darbair ir Dienos (Vilnius) 51:63–69.

- Gary, Romain, Promise at Dawn (Revived Modern Classic), W.W. Norton, 1988, 348p, ISBN 978-0-8112-1016-4

- Huston, Nancy, Tombeau de Romain Gary (Babel, 1997) ISBN 978-2-7427-0313-5

- Bona, Dominique, Romain Gary (Mercure de France, 1987) ISBN 2-7152-1448-0

- Cahier de l'Herne, Romain Gary (L'Herne, 2005)

- Désérable, François-Henri, Un certain M. Piekielny, Gallimard, 2017, ISBN 978-2-07-274141-8

- Schoolcraft, Ralph W. (2002). Romain Gary: The Man Who Sold his Shadow. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3646-7.

- Blanch, Lesley, Romain, un regard particulier (Editions du Rocher, 2009) ISBN 978-2-268-06724-7

- Marret, Carine, Romain Gary – Promenade à Nice (Baie des Anges, 2010)

- Marzorati, Michel (2018). Romain Gary: des racines et des ailes. Info-Pilote, 742 pp. 30–33

- Spire, Kerwin, Monsieur Romain Gary, Gallimard, 2021, ISBN 978-2-07-293006-5

- Stjepanovic-Pauly, Marianne. Romain Gary La mélancolie de l'enchanteur. Editions du Jasmin, ISBN 978-2-35284-141-8

External links[edit]

Media related to Romain Gary at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Romain Gary at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Romain Gary at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Romain Gary at Wikiquote- Romain Gary at IMDb

No comments:

Post a Comment