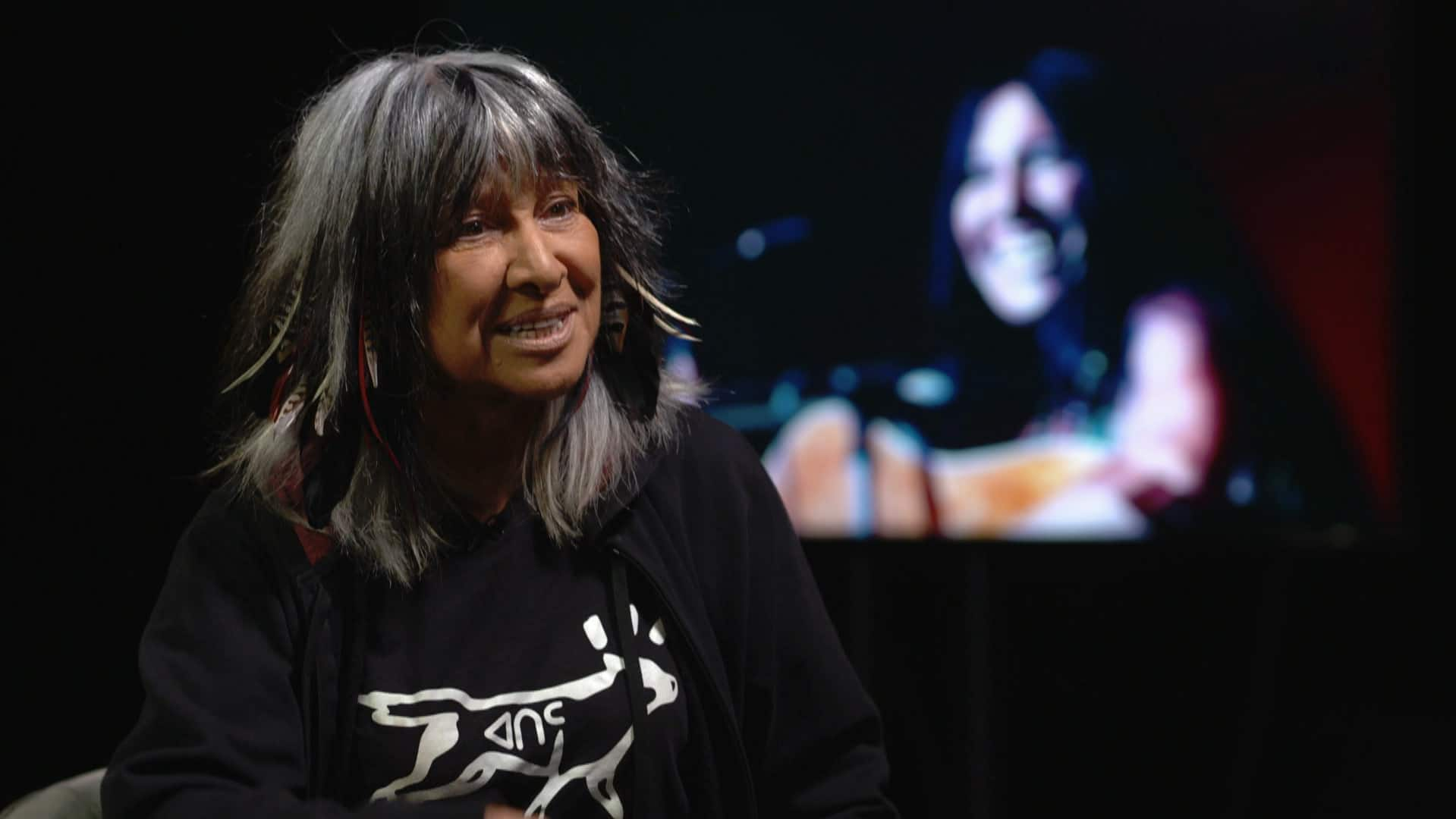

Buffy Sainte-Marie wants more than just an apology from the Pope

Award-winning artist and activist calls for dissolution of Doctrine of Discovery

Warning: This story contains distressing details.

Songwriter, educator and human rights advocate Buffy Sainte-Marie says the Pope's upcoming visit to Canada and expected apology for the church's involvement in the residential school system won't mean a thing if he doesn't call for the dissolution of the Doctrine of Discovery.

"The apology is just the beginning, of course," she said.

The doctrine is an international framework based on a series of decrees from the Pope, called "papal bulls," that were released in the 1400s and 1500s. This framework laid the legal and moral foundation for how Canada and other countries came to be colonized by European settlers.

As Sainte-Marie put it, "The Doctrine of Discovery essentially says it's okay if you're a [Christian] European explorer … to go anywhere in the world and either convert people and enslave, or you've got to kill them."

As noted by the Assembly of First Nations, legal arguments relying on the Doctrine of Discovery continue to affect modern court rulings. As laid out in a 2018 document, the AFN says that doctrine is the root cause of multiple historical and ongoing injustices against Indigenous peoples.

Saint-Marie made the comments during a wide-ranging interview with The National's Adrienne Arsenault. The two discussed recent headlines related to Indigenous people, as well as her long career as an artist and activist.

Sainte-Marie is as outspoken and vibrant as ever. At 81 years old, she bounced into the interview in Toronto with the jovial energy of a child, then proceeded to say she was actually pretty tired. Even an Oscar-winning songwriter and an Indigenous icon isn't immune to the airline problems and delays currently plaguing North America, it seems.

"I just spent three days in Denver Airport sleeping on benches and the floor and everything," she said.

"Yeah, everyone's overwhelmed and it was just awful. But I'm good, I'm glad I'm here."

When asked about her optimistic demeanour and ever-present smile even in the face of troubling times, Sainte-Marie sat back to think before responding.

"I'm kind of the same way as I was when I was a little kid. Very young, I learned that sometimes grown-ups are wrong and kids are right," she said.

"For instance, I was told I couldn't be a musician because I couldn't read music. Therefore you can't be a musician, you know? I was told I couldn't be Indigenous because there aren't any more around here — I've kept that with me my whole life.

"And when somebody comes up to me and says something that to me is just kind of not right on, I make it fun to find out how it could be made better. And that does something for me."

To look back at Sainte-Marie's career is to see an artist determined to use her platform to counter cultural stereotypes and talk about the realities of the treatment of Indigenous people.

In 1966, at the age of 25, she appeared on CBC Television's TBA and played My Country 'Tis of Thy People You're Dying, a song detailing the atrocities of Canada's residential school programs. Before singing it, she told the host about her outrage at stereotypical portrayals of Indigenous people.

WATCH | Buffy Sainte-Marie comments on Indigenous stereotypes in 1966:

"That's the way I have felt all along. But it's not just me," she told Arsenault, after watching the archive clip. "We've all been feeling that way. But I have a platform, so I've been in a position to shoot my mouth off."

Sainte-Marie's message hasn't always been well received, with interviewers asking things like, "Do you worry people say, 'I wonder if she ever has fun?'" in a 1986 interview on Midday, or simply diminishing her concerns by describing her as an "emotional woman" on As It Happens in 1977.

As Arsenault described those interviews as being awkward, Sainte-Marie nodded and summed up the patronizing attitudes she faced this way: "Oh yes, the Little Indian Girl must be mistaken. She's nice and she's cute. We like her. But she's really mistaken. It can't be true."

WATCH | Buffy Sainte-Marie on how some people have tried to dismiss her messages about Indigenous history:

Sainte-Marie said it's an attitude she still faces. Yet she considers it an honour to use the platform she's been given to inform others. To stave off the frustration, she said she leans on something she learned before she became a songwriter, while doing her teaching degree.

"You're not trying to scold the student for not knowing. You're trying to inform them."

As part of her advocacy, she has been trying to get the Canadian Museum For Human Rights in Winnipeg to take a closer and more honest look at atrocities committed in North America. She said she would like to see some of the tools used to torture children at Canada's residential schools on display.

"Children were tortured," she said, referring to the use of an electric chair at St. Anne's Indian Residential School in Fort Albany, Ont. "They want my guitar strap and they want handwritten lyrics … happy, showy things. But I want them to put the damn electric chair right there and to actually show people the doggone Doctrine of Discovery."

When asked about the 2021 discovery of potential unmarked graves on the grounds of the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation, Sainte-Marie said she sees it as progress.

"Here's my attitude. The good news about the bad news is that more people know about it. Of course I was heartbroken like everybody else, and horrified. But it's not as though I didn't know," she said. "The recent discoveries are so important because it's proof."

The life and legacy of Sainte-Marie is the subject of a new five-part CBC podcast entitled Buffy, the first episode of which is being released June 21. Despite the retrospective, Sainte-Marie says she prefers to think about what's next.

She continues to paint and perform. And in recent years she has taken to writing children's books.

"I'm always looking forward," she said.

"I'm like a kid when I'm doing whatever it is that I'm doing. I just don't have anybody giving me any red lights when it comes to art, and so I can go anywhere."

Watch the interview with Buffy Sainte-Marie from The National.

Support is available for anyone affected by the lingering effects of residential school and those who are triggered by the latest reports.

A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for residential school survivors and others affected. People can access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour national crisis line: 1-866-925-4419.

Watch full episodes of The National on CBC Gem, the CBC's streaming service.

Discovery doctrine

| Property law |

|---|

| Part of the common law series |

| Types |

| Acquisition |

| Estates in land |

| Conveyancing |

| Future use control |

| Nonpossessory interest |

| Related topics |

| Other common law areas |

Higher category: Law and Common law |

The discovery doctrine, also called doctrine of discovery, is a concept of public international law expounded by the United States Supreme Court in a series of decisions, most notably Johnson v. M'Intosh in 1823. Chief Justice John Marshall explained and applied the way that colonial powers laid claim to lands belonging to foreign sovereign nations during the Age of Discovery. Under it, European Christian governments could lay title to non-European territory on the basis that the colonisers travelled and "discovered" said territory. The doctrine has been primarily used to support decisions invalidating or ignoring aboriginal possession of land in favor of modern governments, such as in the 2005 case of Sherrill v. Oneida Nation.

The 1823 case was the result of collusive lawsuits where land speculators worked together to make claims to achieve a desired result.[1][2] John Marshall explained the Court's reasoning. The decision has been the subject of a number of law review articles and has come under increased scrutiny by modern legal theorists.

History[edit]

The doctrine of discovery was promulgated by European monarchies in order to legitimize the colonization of lands outside of Europe. Between the mid-fifteenth century and the mid-twentieth century, this idea allowed European entities to seize lands inhabited by indigenous peoples under the guise of "discovering new land", those lands not inhabited by Christians.[3]

In 1452, Pope Nicholas V issued the papal bull Dum Diversas, which authorized Portugal to conquer non-Christians and consign them to "perpetual servitude". His successors issued several bulls confirming or expanding the Portuguese right to subjugate non-European peoples. In 1493, Pope Alexander VI issued the Bulls of Donation justifying Spain's claims to the lands visited by Christopher Columbus in his expeditions of 1492 and later.[4] Portugal ignored the Papal Bull, and in 1494, the two countries concluded the Treaty of Tordesillas, which declared that only non-Christian lands could be colonized under the Doctrine of Discovery, essentially dividing the world unknown to the rest of Europe between them. In 1506, Pope Julius II ratified the Treaty of Tordesillas and sanctioned the "papal line of demarcation" between the Spanish and the Portuguese by issuing the bull "Ea quae pro bono pacis".

In 1792, U.S. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson claimed that this European Doctrine of Discovery was international law which was applicable to the new US government as well.[5] The Doctrine and its legacy continue to influence American imperialism and treatment of indigenous peoples.[6]

Johnson v. M'Intosh[edit]

The plaintiff Johnson had inherited land, originally purchased from the Piankeshaw tribes. Defendant McIntosh claimed the same land, having purchased it under a grant from the United States. It appears that in 1775 members of the Piankeshaw tribe sold certain land in the Indiana Territory to Lord Dunmore, royal governor of Virginia and others. In 1805 the Piankeshaw conveyed much of the same land to William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana Territory, thus giving rise to conflicting claims of title.[7] In reviewing whether the courts of the United States should recognize land titles obtained from Native Americans prior to American independence, the court decided that they should not. Chief Justice John Marshall had large real estate holdings that would have been affected if the case were decided in favor of Johnson. Rather than recuse himself from the case, however, the Chief Justice wrote the decision for a unanimous Supreme Court.[8]

Decision[edit]

Marshall found that ownership of land comes into existence by virtue of discovery of that land, a rule that had been observed by all European countries with settlements in the New World. Legally, the United States was the true owner of the land because it inherited that ownership from Britain, the original discoverer.

Marshall noted:

Chief Justice Marshall noted the 1455 papal bull Romanus Pontifex approved Portugal's claims to lands discovered along the coast of West Africa, and the 1493 Inter caetera had ratified Spain's right to conquer newly found lands, after Christopher Columbus had already begun doing so,[10] but stated: "Spain did not rest her title solely on the grant of the Pope. Her discussions respecting boundary, with France, with Great Britain, and with the United States, all show that she placed it on the rights given by discovery. Portugal sustained her claim to the Brazils by the same title."[9]

United States law[edit]

Marshall pointed to the exploration charters given to the explorer John Cabot as proof that other nations had accepted the doctrine.[10] The tribes which occupied the land were, at the moment of discovery, no longer completely sovereign and had no property rights but rather merely held a right of occupancy. Further, only the discovering nation or its successor could take possession of the land from the natives by conquest or purchase.

The doctrine was cited in other cases as well. With Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), it supported the concept that tribes were not independent states but "domestic dependent nations".[10] The decisions in Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe (1979) and Duro v. Reina (1990) used the doctrine to prohibit tribes from criminally prosecuting first non-Indians, then Indians who were not a member of the prosecuting tribe.[11]

Legal critique[edit]

As the Piankeshaw were not party to the litigation, "no Indian voices were heard in a case which had, and continues to have, profound effects on Indian property rights."[12]

Professor Blake A. Watson of the University of Dayton School of Law finds Marshall's claim of "universal recognition" of the "doctrine of discovery" historically inaccurate.

In reviewing the history of European exploration Marshall did not take note of Spanish Dominican philosopher Francisco de Vitoria's 1532 De Indis nor De Jure belli Hispanorum in barbaros. Vitoria adopted from Thomas Aquinas the Roman law concept of ius gentium, and concluded that the Indians were rightful owners of their property and that their chiefs validly exercised jurisdiction over their tribes, a position held previously by Palacios Rubios. His defense of American Indians was based on a scholastic understanding of the intrinsic dignity of man, a dignity he found being violated by Spain's policies in the New World.[13] However, the legal scholar Anthony Anghie has demonstrated that Vitoria – after applying to the Indians the concept of ius gentium – then found them to be in violation of international law through their resistance to Spanish exploration and missionary activities. By resisting Spanish incursions, Indians were, according to Vitoria, provoking war with the Spanish invaders, thus justifying Spanish conquest of Indian lands.[14]

Marshall also overlooked more recent American experience, specifically Roger Williams's purchase of the Providence Plantations. In order to forestall Massachusetts and Plymouth designs on the land, Williams subsequently traveled to England to obtain a patent which referenced the purchase from the natives. The Rhode Island Royal Charter issued by Charles II acknowledged the rights of the Indians to the land.[7]

Nor does Justice Marshall seem to have taken note of the policy of the Dutch West India Company which only conferred ownership rights in New Netherland after the grantee had acquired title by purchase from the Indian owners, a practice also followed by the Quakers in Pennsylvania Colony.[7]

Watson and others, such as Robert A. Williams Jr., suggest that Marshall misinterpreted the "discovery doctrine" as giving exclusive right to lands discovered, rather than the exclusive right to treaty with the inhabitants thereof.[7]

Contemporary advocacy efforts[edit]

Discovery doctrine has been severely condemned as socially unjust, racist, and in violation of basic and fundamental human rights.[15] The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) noted the Doctrine of Discovery "aos the foundation of the violation of their (Indigenous people) human rights".[8] The eleventh session of the UNPFII, held at the UN's New York headquarters from 7-18 May 2012, had the special theme of "The Doctrine of Discovery: its enduring impact on indigenous peoples and the right to redress for past conquests (articles 28 and 37 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples)," [16] and called for a mechanism to investigate historical land claims, with speakers observing that "The Doctrine of Discovery had been used for centuries to expropriate indigenous lands and facilitate their transfer to colonizing or dominating nations...."[17]

The General Convention of the Episcopal Church, conducted on 8–17 August 2009, passed a resolution officially repudiating the discovery doctrine.[18]

At the 2012 Unitarian Universalist Association General Assembly in Phoenix, Arizona, delegates passed a resolution repudiating the Doctrine of Discovery and calling on Unitarian Universalists to study the Doctrine and eliminate its presence from the current-day policies, programs, theologies, and structures of Unitarian Universalism.[19]

In 2013, at its 29th General Synod, the United Church of Christ followed suit in repudiating the doctrine in a near-unanimous vote.[20]

In 2014, Ruth Hopkins, a tribal attorney and former judge, wrote to Pope Francis asking him to formally revoke the Inter caetera papal bull of 1493.[21]

At the 2016 Synod, 10-17 June in Grand Rapids, Michigan, delegates to the annual general assembly of the Christian Reformed Church rejected the Doctrine of Discovery as heresy in response to a study report on the topic.[22]

At the 222nd General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) (2016), commissioners called on members of the church to confess the church's complicity and repudiate the Doctrine of Discovery. The commissioners directed that a report be written reviewing the history of the Doctrine of Discovery; that report was approved by the 223rd General Assembly (2018), along with recommendations for a variety of additional actions that could be taken by the church at all levels to acknowledge indigenous peoples and to confront racism against them.[23]

In 2016, the Churchwide Assembly of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA), adopted Assembly Action CA16.02.04 entitled Repudiation of the Doctrine of Discovery by a vote of 912-28, describing the Doctrine of Discovery as "an example of the 'improper mixing of the power of the church and the power of the sword'"[24]

Later in 2016, on November 3, a group of 524 clergy publicly burned copies of Inter caetera, a specific papal bull underpinning the doctrine,[25] as part of the Dakota Access Pipeline protests near the Standing Rock Indian Reservation.[26][27]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier Stuart Banner, 2005, pg 171–2

- ^ The Dark Side of Efficiency: Johnson v. M'Intosh and the Expropriation of American Indian Lands, Eric Kades, 148 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1065 2000, pg 148

- ^ Harjo, Susan Shown (2014). Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States & American Indians. Washington, DC: National Museum of the American Indian. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-1-58834-478-6.

- ^ "The Doctrine of Discovery, 1493". www.gilderlehrman.org. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. "The United States Is Founded Upon the Model of European Conquest: Dispose of the Disposable People". Truthout.

- ^ Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne (2014). An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 197–201.

- ^ a b c d "Watson, Blake A., "John Marshall and Indian Land Rights: A Historical Rejoinder to the Claim of "Universal Recognition" of the Doctrine of Discovery", Seton Hall Law Review, Vol.36, 481" (PDF).

- ^ a b Frichner, Tonya Gonnella. (2010). “Preliminary Study of the Impact on Indigenous Peoples of the International Legal Construct Known as the Doctrine of Discovery.” E/C.19/2010/13. Presented at the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, Ninth Session, United Nations Economic and Social Council, New York, 27 Apr 2010.

- ^ a b "Marshall, John. "Johnson v. M'Intosh", 21 U.S. 543, 5 L.Ed. 681, 8 Wheat. 543 (1823)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2014-07-23.

- ^ a b c Newcomb, Steve (Fall 1992). "Five Hundred Years of Injustice". Shaman's Drum: 18–20. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- ^ Robertson, Lindsay G. (June 2001). "Native Americans and the Law: Native Americans Under Current United States Law". Native American Constitution and Law Digitization Project. The University of Oklahoma Law Center. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- ^ Dussias, Allison M., "Squaw Drudges, Farm Wives, and the Dann Sisters' Last Stand: American Indian Women’s Resistance to Domestication and the Denial of Their Property Rights", 77 N.C. L. REV. 637, 645 (1999)

- ^ Pagden, Anthony. Vitoria: Political Writings, Cambridge University Press, 1991

- ^ Anthony Anghie, Imperialism, Sovereignty, and the Making of International Law (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005): Ch. 1 “Francisco de Vitoria and the Colonial Origins of International Law.”

- ^ "Department of Economic and Social Affairs - Social Policy and Development Division; Home". 1map.com.

- ^ "UNPFII Eleventh Session", United Nations Economic and Social Council, New York. Retrieved 15 Sep 2019.

- ^ United Nations. (2012-05-08). “‘Doctrine of Discovery’, Used for Centuries to Justify Seizure of Indigenous Land, Subjugate Peoples, Must Be Repudiated by United Nations, Permanent Forum Told” (media release). HR/5088. Forum on Indigenous Issues, Eleventh Session, United Nations Economic and Social Council, New York. Retrieved 15 Sep 2019.

- ^ Schjonberg, Mary Frances. "General Convention renounces Doctrine of Discovery", Episcopal Life Online, 27 August 2009.

- ^ "Doctrine of Discovery and Rights of Indigenous Peoples". UUA.org. February 17, 2016.

- ^ "General Synod delegates overwhelmingly approve resolution repudiating the Doctrine of Discovery". www.ucc.org.

- ^ Hopkins, Ruth. "A Letter to Pope Francis: Abolish the Papal Bull Behind Colonization!". Indian Country Today.

- ^ "Synod 2016 Rejects Doctrine of Discovery as Heresy". Retrieved 2016-07-21.

- ^ PC(USA) "Doctrine of Discovery Report". For action by the 222nd General Assembly (2016), see business item 11-17; for actions by the 223rd General Assembly (2018), see business item 10-12 and 10-13.

- ^ "RepudiationDoctrineofDiscoverySPR2016" (PDF).

- ^ "The Doctrine of Discovery Helped Define Native American Policies".

- ^ "Clergy repudiate 'doctrine of discovery' as hundreds support indigenous rights at Standing Rock". 4 November 2016.

- ^ "Image Gallery: 500 interfaith clergy and laity answered the call to stand with Standing Rock". 3 November 2016.

Further reading[edit]

- Lawlor, Mary. Public Native America: Tribal Self Representation in Casinos, Museums and Powwows, Rutgers University Press, 2006

- Robert J. Miller and Elizabeth Furse, Native America, Discovered and Conquered: Thomas Jefferson, Lewis & Clark, and Manifest Destiny, Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2006

- Miler, Robert J., and Jacinta Ruru. "An Indigenous Lens into Comparative Law: The Doctrine of Discovery in the United States and New Zealand". West Virginia Law Review 111 (2008): 849.

- Miller, R. J., Ruru, J., Behrendt, L., & Lindberg, T. (2010). Discovering indigenous lands: The doctrine of discovery in the English colonies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

External links[edit]

- "The Doctrine of Discovery, 1493". www.gilderlehrman.org. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

発見 (国際法)

国際法における発見 (はっけん) は、かつて領域権原のひとつとして認められるか争われた概念である[1]。今日では無主地の発見は「未成熟の権原」にとどまるものであり、その後妥当な期間内に現実の占有行為がない場合には完全な領域権原の取得原因とは認められない[2]。

沿革[編集]

16世紀半ばごろまでには発見を完全な領域権原の取得原因として認める立場があった[2]。こうした立場の中にも、単に無主地を発見すればその後に占有意思を示す行為がなくても領域権原を取得できるとする立場と、それだけでは不十分で国旗掲揚や標柱の設置などのような占有の意思を示す象徴的行為まで必要とする立場があった[2]。こうした立場に従えば、発見のみによって有効に領域権原を取得できることとなる[2]。

ところが19世紀以降になると、世界的に無主地がほとんどなくなり、発見だけではなく実効的占有を領域権原取得の要件とするようになっていき、発見だけを理由にその地域に排他的な影響力を及ぼすことは許されなくなっていった[2]。19世紀後半から20世紀前半ごろになると、領域権原の取得原因は先占、添付、割譲、時効、征服の5つに限られるとする考え方が一般的になっていく[3]。今日では無主地を発見したのみでその後の現実の占有行為がない場合には領域権原の取得原因とは認められず、後述する「未成熟な権原」にとどまるものとされている[2]。

未成熟の権原[編集]

今日において発見は確定的な領域権原を設定するものではなく、「未成熟の権原」となるに過ぎないとされている[2]。領域権原の取得原因である先占として認められるためには発見のみでは不十分であり、その土地の使用や定住を伴う物理的支配権の行使や確立が必要とされている[4]。そのような立場を示したものとして、16世紀初めに島を発見したスペインの領有権を条約により継承したとするアメリカと、原住民との協定や18世紀以降の主権行使の事実を主張したオランダの間で島の領有権が争われた1928年のパルマス島事件常設仲裁裁判所判決があげられる[4]。同判決において裁判所は、決定的期日の時点で発見に基づくスペインの主権が存続していたかを検討し、もし16世紀に発見のみによってスペインの権原が認められたとしても、その後のスペインの権利の継続的な存在は決定的期日の時点で有効な法によって判断されなければならないとして、単なる発見の事実は無主地の先占による領域権原の取得を認めるには不十分だと判断した[4]。発見による「未成熟の権原」は、他国による継続的かつ平和的な主権の行使に優越しないと判断されたのである[2]。

出典[編集]

参考文献[編集]

- 小寺彰、岩沢雄司、森田章夫 『講義国際法』有斐閣、2006年。ISBN 4-641-04620-4。

- 杉原高嶺、水上千之、臼杵知史、吉井淳、加藤信行、高田映 『現代国際法講義』有斐閣、2008年。ISBN 978-4-641-04640-5。

- 筒井若水 『国際法辞典』有斐閣、2002年。ISBN 4-641-00012-3。

- 山本草二 『国際法【新版】』有斐閣、2003年。ISBN 4-641-04593-3。

No comments:

Post a Comment