Wednesday, August 25, 2021

The Chair | Netflix Official Site

What is Critical Race Theory? A Brief History Explained - The New York Times

Critical Race Theory: A Brief History

How a complicated and expansive academic theory developed during the 1980s has become a hot-button political issue 40 years later.

Criticism of “critical race theory” coincided with widespread demonstrations. Thousands gathered in Washington on Aug. 28, 2020, in support of social justice and commemorating the historic March on Washington and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech on that date in 1963.

By Jacey Fortin

July 27, 2021

About a year ago, even as the United States was seized by protests against racism, many Americans had never heard the phrase “critical race theory.”

Now, suddenly, the term is everywhere. It makes national and international headlines and is a target for talking heads. Culture wars over critical race theory have turned school boards into battlegrounds, and in higher education, the term has been tangled up in tenure battles. Dozens of United States senators have branded it “activist indoctrination.”

But C.R.T., as it is often abbreviated, is not new. It’s a graduate-level academic framework that encompasses decades of scholarship, which makes it difficult to find a satisfying answer to the basic question:

What, exactly, is critical race theory?

First things first …

The person widely credited with coining the term is Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, a law professor at the U.C.L.A. School of Law and Columbia Law School.

Asked for a definition, she first raised a question of her own: Why is this coming up now?

Image

Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw speaking at the Women’s March in Los Angeles in 2018.Credit...Amanda Edwards/Getty Images

“It’s only prompted interest now that the conservative right wing has claimed it as a subversive set of ideas,” she said, adding that news outlets, including The New York Times, were covering critical race theory because it has been “made the problem by a well-resourced, highly mobilized coalition of forces.”

Some of those critics seem to cast racism as a personal characteristic first and foremost — a problem caused mainly by bigots who practice overt discrimination — and to frame discussions about racism as shaming, accusatory or divisive.

But critical race theorists say they are mainly concerned with institutions and systems.

“The problem is not bad people,” said Mari Matsuda, a law professor at the University of Hawaii who was an early developer of critical race theory. “The problem is a system that reproduces bad outcomes. It is both humane and inclusive to say, ‘We have done things that have hurt all of us, and we need to find a way out.’”

OK, so what is it?

Critical race theorists reject the philosophy of “colorblindness.” They acknowledge the stark racial disparities that have persisted in the United States despite decades of civil rights reforms, and they raise structural questions about how racist hierarchies are enforced, even among people with good intentions.

Proponents tend to understand race as a creation of society, not a biological reality. And many say it is important to elevate the voices and stories of people who experience racism.

But critical race theory is not a single worldview; the people who study it may disagree on some of the finer points. As Professor Crenshaw put it, C.R.T. is more a verb than a noun.

“It is a way of seeing, attending to, accounting for, tracing and analyzing the ways that race is produced,” she said, “the ways that racial inequality is facilitated, and the ways that our history has created these inequalities that now can be almost effortlessly reproduced unless we attend to the existence of these inequalities.”

Professor Matsuda described it as a map for change.

“For me,” she said, “critical race theory is a method that takes the lived experience of racism seriously, using history and social reality to explain how racism operates in American law and culture, toward the end of eliminating the harmful effects of racism and bringing about a just and healthy world for all.”

Why is this coming up now?

Opponents of the academic doctrine known as critical race theory protesting outside the Loudoun County School Board office in Ashburn, Va., on June 22.Credit...Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters

Like many other academic frameworks, critical race theory has been subject to various counterarguments over the years. Some critics suggested, for example, that the field sacrificed academic rigor in favor of personal narratives. Others wondered whether its emphasis on systemic problems diminished the agency of individual people.

This year, the debates have spilled far beyond the pages of academic papers.

Last year, after protests over the police killing of George Floyd prompted new conversations about structural racism in the United States, President Donald J. Trump issued a memo to federal agencies that warned against critical race theory, labeling it as “divisive,” followed by an executive order barring any training that suggested the United States was fundamentally racist.

His focus on C.R.T. seemed to have originated with an interview he saw on Fox News, when Christopher F. Rufo, a conservative scholar now at the Manhattan Institute, told Tucker Carlson about the “cult indoctrination” of critical race theory.

Use of the term skyrocketed from there, though it is often used to describe a range of activities that don’t really fit the academic definition, like acknowledging historical racism in school lessons or attending diversity trainings at work.

The Biden administration rescinded Mr. Trump’s order, but by then it had already been made into a wedge issue. Republican-dominated state legislatures have tried to implement similar bans with support from conservative groups, many of whom have chosen public schools as a battleground.

“The woke class wants to teach kids to hate each other, rather than teaching them how to read,” Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida said to the state’s board of education in June, shortly before it moved to ban critical race theory. He has also called critical race theory “state-sanctioned racism.”

According to Professor Crenshaw, opponents of C.R.T. are using a decades-old tactic: insisting that acknowledging racism is itself racist.

“The rhetoric allows for racial equity laws, demands and movements to be framed as aggression and discrimination against white people,” she said. That, she added, is at odds with what critical race theorists have been saying for four decades.

What happened four decades ago?

Derrick Bell, a Harvard Law School professor, walking with a group of students protesting the law school’s practice of not granting tenure to female professors.Credit...Steve Liss/Time Life Pictures via Getty Images

In 1980, Derrick Bell left Harvard Law School.

Professor Bell, a pioneering legal scholar who died in 2011, is often described as the godfather of critical race theory. “He broke open the possibility of bringing Black consciousness to the premiere intellectual battlefields of our profession,” Professor Matsuda said.

His work explored (among other things) what it would mean to understand racism as a permanent feature of American life, and whether it was easier to pass civil rights legislation in the United States because those laws ultimately served the interests of white people.

After Professor Bell left Harvard Law, a group of students there began protesting the faculty’s lack of diversity. In 1983, The New York Times reported, the school had 60 tenured law professors. All but one were men, and only one was Black.

The demonstrators, including Professors Crenshaw and Matsuda, who were then graduate students at Harvard, also chafed at the limitations of their curriculum in critical legal studies, a discipline that questioned the neutrality of the American legal system, and sought to expand it to explore how laws sustained racial hierarchies.

“It was our job to rethink what these institutions were teaching us,” Professor Crenshaw said, “and to assist those institutions in transforming them into truly egalitarian spaces.”

The students saw that stark racial inequality had persisted despite the civil rights legislation of the 1950s and ’60s. They sought, and then developed, new tools and principles to understand why. A workshop that Professor Crenshaw organized in 1989 helped to establish these ideas as part of a new academic framework called critical race theory.

What is critical race theory used for today?

OiYan Poon, an associate professor with Colorado State University who studies race, education and intersectionality, said that opponents of critical race theory should try to learn about it from the original sources.

“If they did,” she said, “they would recognize that the founders of C.R.T. critiqued liberal ideologies, and that they called on research scholars to seek out and understand the roots of why racial disparities are so persistent, and to systemically dismantle racism.”

To that end, branches of C.R.T. have evolved that focus on the particular experiences of Indigenous, Latino, Asian American, and Black people and communities. In her own work, Dr. Poon has used C.R.T. to analyze Asian Americans’ opinions about affirmative action.

That expansiveness “signifies the potency and strength of critical race theory as a living theory — one that constantly evolves,” said María C. Ledesma, a professor of educational leadership at San José State University who has used critical race theory in her analyses of campus climate, pedagogy and the experiences of first-generation college students. “People are drawn to it because it resonates with them.”

Some scholars of critical race theory see the framework as a way to help the United States live up to its own ideals, or as a model for thinking about the big, daunting problems that affect everyone on this planet.

“I see it like global warming,” Professor Matsuda said. “We have a serious problem that requires big, structural changes; otherwise, we are dooming future generations to catastrophe. Our inability to think structurally, with a sense of mutual care, is dooming us — whether the problem is racism, or climate disaster, or world peace.”

Islam in Australia - Wikipedia

Time and place: The Adelaide Mosque

Time and place: The Adelaide Mosque

In the first article in a new series about significant South Australian places, we examine the history of Australia’s oldest mosque.

Tucked away in Little Gilbert Street is an unassuming building distinguishable only by four white minarets. This is the oldest mosque still in use on the Australian mainland, and the first to be built in an Australian city.

The Adelaide Mosque was completed in 1889, serving as a spiritual meeting place for the Muslim cameleers who were working in the outback north of Adelaide and stopping here in between jobs or trips.

Referred to collectively as ‘Afghan’ by the dominant British-Australian population at the time, Muslim cameleers actually came from Afghanistan, Balochistan and areas of north-west India (now Pakistan). The first migrant cameleers were brought out by Elder & Co. with 124 imported camels to work at Beltana Station, north of Port Augusta, in 1865.

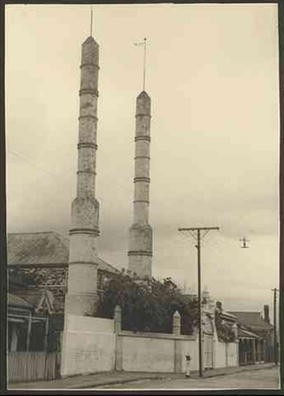

The Mosque pictured in December 1928. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia SLSA: B21920, No known copyright restrictions

Other migrant cameleers followed and, with their camels, provided transport for explorers, the growing wool industry and stores in the Outback. Muslim cameleers played a vital part in building the Overland Telegraph Line from Darwin to Adelaide, completed in 1872.

The distinctive minarets were not added until 1903. The surrounding garden had grown by then, and was described in detail that year by The Advertiser: ‘The mosque is situated in a garden filled with flowers of all colors, and the effect is enhanced here and there by evergreen trees. On one side of the mosque are a number of cottages, around which vines have been trained, with the result that they appear very picturesque.”

View through arches of Adelaide Mosque to garden and pool in 1937.

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B 7286, Public Domain

While some cameleers moved on following work in Australia and elsewhere, and others returned to their country of origin, others settled in South Australia becoming part of the community. Many of the Islamic community in Adelaide lived in the south-west corner of the city, near the mosque that played such an important role in Muslim lives.

In the subsequent years, the mosque fell into disrepair.

Post-war migration from Europe and Indonesia rebuilt the Muslim population. Bosnian migrants in 1952 found “ancient turbaned men’, the youngest aged 87 and the oldest 117 years, still living in its decaying shelter. The younger men, who cared for the old cameleers until they died, took on the task of restoring the mosque.

Get InDaily in your inbox. Daily. The best local news every workday at lunch time.

The Adelaide Mosque again became a place of prayer, this time for Muslim migrants from Lebanon, Pakistan, Indonesia, Malaysia and areas of the former Yugoslavia.

It is still used today, and it also serves as a reminder today of the pioneering spirit of the original cameleers.

For more information go here.

‘Time and place’ is a new series about significant places in South Australia, brought to you by a partnership of InDaily and the History Trust of South Australia.

Building identity in the colonial city: the case of the Adelaide Mosque | SpringerLink

Published: 16 September 2015

Building identity in the colonial city: the case of the Adelaide MosqueKatharine Bartsch

Contemporary Islam volume 9, pages247–270 (2015)Cite this article

4038 Accesses

3 Citations

38 Altmetric

Metricsdetails

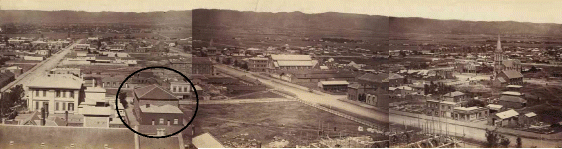

A panorama of exclusion

In 1865, Townsend Duryea (1823–1888), a mining engineer cum photographer hailing from Long Island, New York, created a panoramic image of the colonial city of Adelaide, capital of the free province of South Australia, inaugurated in 1836.Footnote1 This early panorama, taken from the recently completed tower of the Adelaide Town Hall, depicts the wide avenues, generous city parks and the precise grid of a colonial city that has long been praised internationally as an exemplar of city planning (Figs. 1, 2 and 3). Within this orderly framework, Duryea captures the vigorous building activity of this colonial settlement, including the edifices of more than 20 Christian parishes who staked their claim in this so-called City of Churches. The Duryea panorama depicts a clearly defined spatial hierarchy. While the pretentious structures of the colonial elite occupy the civic centre and the desirable plots of land to the north (adjacent the river) and east of the Town Hall (looking toward the hills), the city fringe, particularly the areas west and south of the city, was the site of industry, the rail yards and the home of impoverished immigrants. Clearly defined spatial boundaries further divide the civilised city from wild nature. Beyond the city fringe, the Duryea panorama depicts the sprawling Adelaide plains, bounded by the Mount Lofty Ranges to the east and the Gulf of St Vincent to the west. These views further highlight the early European exploitation of this hinterland. Visible is the destruction of the pre-European vegetation (Kraehenbuehl 1996) due to agricultural and grazing practices, the fabrication of tools and furniture, and the supply of fuel and building materials, including the timber scaffold upon which Duryea perched his tripod.

Fig. 1

View of Adelaide from the Town Hall Tower, looking north, identifying the Chalmers Free Church of Scotland on North Terrace (circle). Townsend Duryea, 1865. State Library of South Australia B5099/1 and B5099/2 (composite image by author). (No known copyright restrictions)

Full size image

Fig. 2

View of Adelaide from the Town Hall Tower, looking east, identifying the Freeman Street Congregational Chapel (circle). Townsend Duryea, 1865. State Library of South Australia B5099/4, B5099/5 and B5099/6 (composite image by author). (No known copyright restrictions)

Full size image

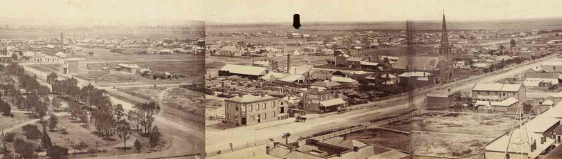

Fig. 3

View of Adelaide from the Town Hall Tower, looking south west, identifying the approximate location of the Adelaide Mosque which was begun in 1889 (arrow). Townsend Duryea, 1865. State Library of South Australia B5099/9, B5099/10 and B5099/11 (composite image by author). (No known copyright restrictions)

Full size image

This exploitation of the hinterland is but one of the many processes that characterise Adelaide as an example of settler colonialism, concisely defined by urban historian Penelope Edmonds:

The settler-colonial city was a site where the appropriation of Indigenous land was coupled with aggressive allotment and property speculation and where property relations were constructed quickly through the rhetorical celebrations of making a white, civilised British space. Throughout the nineteenth century, these settler towns and cities became nodes in active trans-imperial networks, through which bodies, ideas and capital increasingly flowed in the circuits of empire. The resultant and rapid increase of immigrant populations to these colonial towns and the growth of industrialization over the latter part of the nineteenth century drove a continually developing set of regulations for the ways in which Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples could inhabit city spaces. (Edmonds 2010: 7)

Adelaide exhibited many characteristics of the settler-colonial city. Hence, given the concomitant marginalisation and suppression of Indigenous peoples, indentured labourers and poor immigrants in the city, and the ongoing erasure of their contributions in colonial historiography, the construction of a permanent mosque in the city of Adelaide is unexpected. Together with the purpose-built Shah Jahan Mosque in Woking, Surrey, UK—also built in 1889—the Adelaide Mosque is one of the earliest extant mosques in a “western” city.Footnote2 How, then, did non-Indigenous minorities territorialise the city?

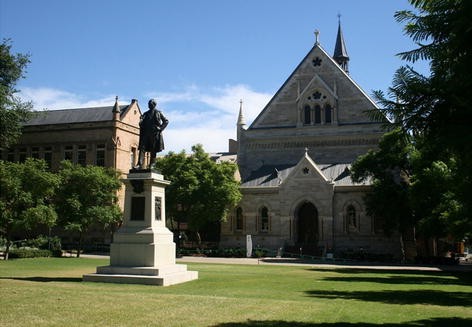

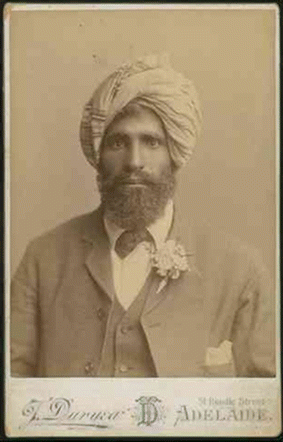

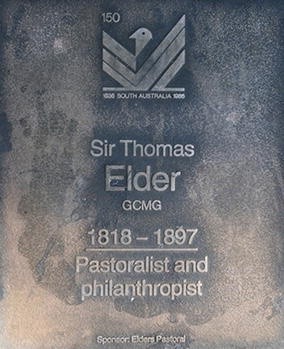

The Duryea panorama offers a useful starting point to review the place and agency of Adelaide’s small Muslim community. From Duryea’s vantage point, Chalmers Free Church of Scotland (a branch of Presbyterianism), opened in 1851, is visible. It occupies a prime position on North Terrace, the premier civic boulevard of the settlement (Fig. 4). Today, the church stands directly opposite an imposing statue (unveiled in 1903) of another Scotsman, Sir Thomas Elder (1818–1897; Fig. 5), businessman, pastoralist, financier and philanthropist, who bequeathed extraordinary sums to the University of Adelaide, where the statue is located, as well as to the Presbyterians, Anglicans and Methodists. This same statue commemorates the camels that Elder brought out to Australia in the 1860s (Figs. 6). The camels are relegated to the rear of the statue, but represented nonetheless, the only civic marker from the period that does so. The “Afghan” handlers are absent. However, Duryea’s extant collection of photographs of dignitaries and pioneers commemorates a single cameleer, Bejah Dervish (1862?–1957, Fig. 7; Hankel 1979a).Footnote3 Elder is also represented (Fig. 8). Elder’s statue and Duryea’s recognition of Dervish are rare colonial gestures towards the “overlapping territories and intertwined histories” of Adelaide’s pioneers (Said 1994: 72).

Fig. 4

Chalmers Church, built in the neo-Gothic style and opened in 1851. (Photograph by author)

Full size image

Fig. 5

Statue of Sir Thomas Elder in granite and bronze by Albert Drury, 1903. The statue is located in front of Elder Hall, School of Music, The University of Adelaide. Elder donated nearly £100,000 pounds to the University of Adelaide between 1874 and 1897, including £21,000 to the School of Music. He donated a further £10,000 to Presbyterians, £4000 to Anglicans for their cathedral and £4000 to Methodists for Prince Alfred College. (Photograph by author)

Full size image

Figs. 6

a Detail of the bronze relief on the granite plinth that elevates the statue of Sir Thomas Elder, The University of Adelaide, by Albert Drury, 1903. This view depicts camels bearing loads. The rider may represent David Lindsay (1856–1922), leader of the Elder Scientific Exploring Expedition (1891–1892), based on comparison with contemporary photos and particularly an engraving on wood, printed in The Illustrated Australian in 1892, of Lindsay that depicts his broad-brimmed hat and a similar style of beard, trousers and boots. (Photograph by author). b Further detail of the bronze relief depicting camels by Albert Drury, 1903. (Photograph by author)

Full size image

Fig. 7

Portrait photograph of cameleer Bejah Dervish (1862?–1957) taken in 1890 by Townsend Duryea (1823–1888). State Library of South Australia B11209. (No known copyright restrictions)

Full size image

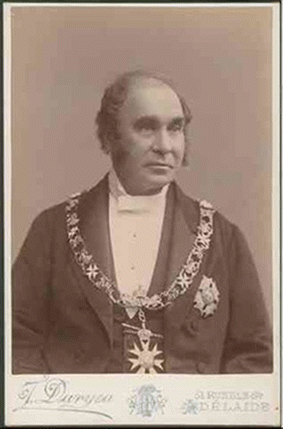

Fig. 8

Portrait photograph of Sir Thomas Elder (1818–1897, K.C.M.G. 1878, G.C.M.G. 1887) taken in 1887 by Townsend Duryea (1823–1888). State Library of South Australia B11292. (No known copyright restrictions)

Full size image

Acknowledging the contributions of Australia’s Muslim pioneers to the exploration, territorial expansion and settlement of inland Australia; to transport, haulage and communication that linked remote settlements within the vast and inhospitable wilderness; and to the inland economy, which was inextricably tied to the wealth of the settler-colonial city, this paper seeks to offer a fresh reading of the place and agency of Muslims in this colonial city, through a specific analysis of the Adelaide Mosque. This analysis is based on architectural drawings, comparison with other colonial buildings, reflection on the mosque’s function and biographical data of cameleers affiliated with the mosque. The aim is to appreciate their crucial contribution to the development of the inland economy—most significantly mining and pastoralism—which was inextricably linked to the fortunes of the settler-colonial city and which continues to underpin the national economy today.Footnote4

This examination of the intertwined histories of individuals such as Elder and Dervish seeks to enhance understanding of the long history of Islam in Australia and counter the portrayal of Muslims as new arrivals in Australia. Islam is continually maligned in the Australian media (Ganter 2008) and is represented by Nahid Kabir as the “current enemy” (2006, 2007). Emphasis is placed on the otherness of Islam, and the difference of an Islamic way of life, that is distanced from Australian culture and society (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission 2003; Northcote et al. 2006; Saniotis 2004) with alarming implications in the political arena and in everyday social and spatial practices. This distance is acute in public debates about the construction of contemporary mosques (Bouma 1994; Humphrey 2010). Acknowledging the fantasy of a white Australian history and the deep histories of contact, as Ganter (2008) contends, it is critical to challenge fixed hierarchical notions of belonging. To do so, this paper begins by contextualising the role of the cameleers in the exploration of the arid Australian interior; it links the fortunes of these outback pioneers to the commission of the Adelaide Mosque. The paper, then, examines the physical structure of the mosque, reflecting on this as an increasingly confident projection of the cameleers’ identity. The mosque is interpreted according to Bourdieu’s concept of habitus, as a type of “objectivated cultural capital”, a dormant form whose value is “activated strategically in the present by those seeking to modify their incorporated cultural capital” through social practices and narratives of belonging (Leach 2005: 298); acts of territorialisation. The intent is to locate the mosque at the level of the neighbourhood to appreciate the claims to inhabit the colonial settler city as active agents and as a basis for further recognition and celebration of the histories and identities of Australian Muslims today.

Territorial expansion in Australia

To investigate notions of belonging and the territorialisation of urban space in Adelaide, and concomitant symbolic and visual expressions of identity, it is necessary to (1) appreciate the relationship between territorial claims in the city and territorial exploitation of the interior and (2) move beyond anonymous or monolithic representations of the “Afghans” to appreciate the contributions of individual pioneers in the colonial period and, specifically, their attachment to the Adelaide Mosque. As Edward Said argues in Culture and Imperialism, “we must speak of overlapping territories, intertwined histories common to men and women, whites and non-whites, dwellers in the metropolis and on the peripheries, past as well as present and future” (Said 1994: 72). To examine these overlapping territories and intertwined histories in the case of South Australia, this paper draws particularly on the important work, based on wide-ranging archival research, oral histories and material artefacts, of historians Christine Stevens and Philip Jones, as well as entries in the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Jones’s work, in particular, has generated a detailed biographical list of more than 1200 cameleers.Footnote5 Importantly, these studies highlight the specific contributions of the cameleers to the process of European exploration and territorial expansion.Footnote6 The significance of the physical placemaking of the cameleers was also acknowledged in the listing of the mosque on the South Australian State Heritage Register (City of Adelaide 1990). However, these studies do not link these specific biographical data to the mosque, nor examine the mosque in relation to the urban fabric, which is the goal of this paper.

Islam has a long history in Australia and, as Regina Ganter argues, “Muslims are not only a long-standing part of the Australian social landscape (rather than ‘recent invaders’), they are in fact its most long-standing non-Indigenous segment, because they entered northern Australia well before any Christians” (Ganter 2008: 482).Footnote7 Evidence of “Afghan” settlement is distributed throughout South, Central and Western Australia. Historian Abdullah Saeed estimates that 3000 “Afghans” were employed across Australia in the late nineteenth century (Saeed 2003: 3–7; see also Deen n.d.; Jones 1993). By the 1880s, trade and management of the beasts was monopolised by migrant “Afghans”, who specifically comprised Afridi, Durrani, Ghilzai and Baluchi tribesmen from Afghanistan and the northwest frontier province of British India (Ganter 2008; Jones and Kenny 2010: 28–29). Bejah Dervish, for example, migrated from Baluchistan circa 1889. The majority of cameleers were distinguished by their Islamic faith, and archival photographs held at the State Library of South Australia (SLSA) provide evidence of the simple outback mosques (built of mud and bough and, in time, corrugated iron), constructed by the cameleers, that served the practical needs for communal prayer in remote settlements and stations (Fig. 9).

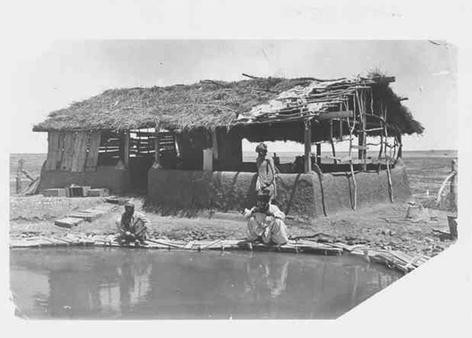

Fig. 9

Mosque at Hergott Springs (now Marree), c. 1884. State Library of South Australia B15341. (No known copyright restrictions)

Full size image

In Tin Mosques and Ghantowns (1989, reprinted in 2002), the first substantial study of the cameleers, historian Christine Stevens gives an enthralling account of the cameleers’ life in Australia through firsthand historical documents. She traces the arrival of “Afghans” in Australia, their employment in railroad construction, their lives in the bush and the city, their struggle against alienation from Anglo-Australian society and, finally, their marginalisation and obliteration from the pages of Australian history (see also Deen n.d.; Kabir 1993). However, despite the title of Stevens’s engaging study, the built environment receives little attention. Moreover, together with Rajkowski (1987), and more recently Scriver (2004), Stevens’s romantic use of the term “Ghantown” portrays remote, isolated, exotic communities set apart from colonial cities.Footnote8 In her conclusion, Stevens highlights the need for further research examining the material evidence of Afghan settlement.

To understand the origins of the Adelaide Mosque, it is necessary to reflect on the fortunes of its founders, beginning with the arrival of the first cameleers, which was primarily facilitated by Sir Thomas Elder, who arrived in Adelaide in 1854 to expand the family business. Thomas’s second eldest brother Alexander Lang Elder had already established a thriving business in trade and transport of goods by sea in the business district of Adelaide on Rundle Street. By the early 1840s, the brothers were taking advantage of the rich opportunities to be found in copper mining and wool. However, it was Thomas who would realise these opportunities to their fullest potential, firstly through the partnership of Elder, Stirling and Co., established with other local entrepreneurs, and later through Elder, Smith and Co., which would become one of the largest international wool merchants in the nineteenth century. This entrepreneurship exemplified Adelaide’s position amidst the imperial flow of capital, as Edmonds contends, despite the antipodean location. This success was entirely dependent on Elder’s firsthand experience of the harsh conditions of the arid Australian interior and his immediate appreciation of the challenges. His foresight and initiative are key to the subsequent exploration, development and settlement of the inland, while his financial success exemplifies the crucial link between the resource-rich interior and the urban (and national) economy.

By 1860, Elder had joined forces with fellow pastoralist Samuel Stuckey to explore the possibilities of camels as a viable solution for the transport needs on his vast outback stations. He was not the first. In 1830, retired East India officer T. J. Maslan had recommended camels for the purpose of inland exploration in Australia, although he never travelled to the continent. In 1839, Governor Gawler of South Australia had proposed that camels would be a superior alternative to horses and bullocks for the penetration of Australia’s arid interior. The Horrocks expedition of 1846 had proved the hardiness of a single camel in the South Australian outback, and the failed attempt of Benjamin Herschel Babbage had proved the unsuitability of horses in 1858. In the same year, the “Camel Troop Carrying Company” had petitioned the South Australian parliament for funds to import camels for “the business of exploration, and opening up the resources of the Colony” (Jones and Kenny 2010: 38). It was not until 1860 that camel-handling knowledge had become crucial to a lengthy desert campaign. The Victorian Government had supplied the ill-fated Burke and Wills expedition with 24 camels and three cameleers: Dost Mahomed, Hassam Khan and Belooch, who had all arrived in Melbourne from Karachi in 1860 to fulfil 3-year contracts. Written in Dari and English, these contracts were typical arrangements for this type of indentured labour. However, the scale and longevity of Elder’s enterprising activities far outstripped earlier initiatives to manage camels in Australia.

In 1865, the same year the Duryea panorama was created, Elder imported 124 camels and 31 cameleers from Kandahar, Kabul and Sindh. During this period, with the assistance of camels to navigate the vast pastoral territories and to haul wool to the railhead or to Port Augusta, he took up vast land holdings, including Paratoo (3000 km2), Umberatana, Mt Lyndhurst, Blanchewater (3000 km2) and Beltana (900 km2), the last of which was established as a highly successful camel stud. In 1866, Elder won the mail contract between Blanchewater and Lake Hope for £150 per annum. One hundred Beltana camels enabled the construction of the overland telegraph line from Adelaide to Darwin in 1872, transforming Australia’s communication. Further to the arrival of small numbers of cameleers at Port Augusta, Elder imported an additional 300 camels in 1884, accompanied by 59 cameleers. Cameleers were employed for transport and haulage within and between large remote “stations” (in Australia, a large sheep or cattle farm) and settlements and were vital to the transport of wool from Elder’s remote stations to the port.

However, Elder’s most significant contribution was to exploration. He himself was an avid traveller, as evidenced by his journeys to Palestine (where, in 1857, he had his first experience in camel riding), Algeria and Spain.Footnote9 He funded several major expeditions, including those of Peter Egerton Warburton from Central Australia across the Great Sandy Desert to the Indian Ocean (4000 miles) with Saleh Mahomed (d. 1962; Jones 2011) and Halleem in 1872–1873; Ernest Giles’s (1835–1897; Green 1972) expeditions with Saleh Mahomed and Halleem in 1875 and 1876, aptly described in the title of Giles’s diaries Australia Twice Traversed (Giles 1964)Footnote10; and the Royal Geographical Society of South Australia’s expedition led by David Lindsay (1856–1922; Edgar 1986) from 1891 to 1892 with Hadji Shah Mahomet (d. circa 1887; Jones 2011), Mahyedin, Alumgool, Mahmoud Azim (also known as Abdul), Abdul and Joorak Mahomed. This expedition was also known as the Elder Scientific Exploring Expedition. These teams explored the most inhospitable territory of the western deserts located between Central Australia and the Indian Ocean. Warburton, Giles and Lindsay set off from Beltana.

In addition to these expeditions, the cameleers were essential to other major expeditions, including the Gosse expedition (1872) with Kamran, Jemma Khan and Allanah; the Horn Scientific Exploration Expedition in 1894 with Moosha and Guzzie Balooch; the Calvert Expedition led by Lawrence Allen Wells (1860–1938, Fig. 10; Steele 1990) between 1896 and 1897 with Bejah Dervish (c. 1862–1957) and Said Ameer; the Strzelecki Expedition (1916) with camel leader Mahomet Salaam (contracted by camel merchant Moosha Balooch, who initially worked for Elder, Smith and Co. in the 1880s); and the Madigan Simpson Desert Expedition (1939) led by Cecil Madigan (1889–1947; Parkin 1986) with Abdul Jabbar Bejah (b. 1919; Jones 2011) and Nur Mahommed Moosha.

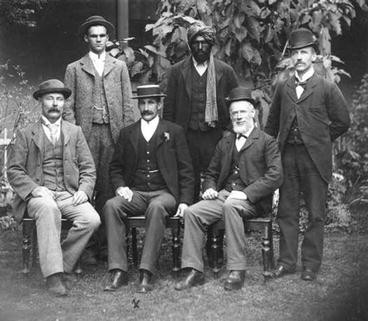

Fig. 10

The Calvert Scientific Exploring Expedition, 1890. State Library of South Australia PRG 280/1/8/379. (No known copyright restrictions)

Full size image

The contributions of the cameleers might be dismissed as examples of indentured labour. However, recent scholarship by Jones, in particular, reveals the European explorers’ respect for the cameleers; many of the explorers owed their lives to the skills of the cameleers. Accomplished explorers forged strong bonds with little-known cameleers, and their daring exploits, highly praised in the journals of the European explorers, are equally worthy of recognition in the annals of Australian history. The journals kept by these explorers constitute the earliest literary records of Muslims in Australia. For example, the 1896 expedition journal of L. A. Wells, who was commissioned to explore “the remaining blanks of Australia”, in the region of the Fitzroy River in northern Western Australia, dispels prevailing oppositions between European and Asian, leader and subordinate, or the familiar and the strange, which were diluted in the hostile terrain (Wells 1896: n.p.). Wells describes his team members on equal terms in their mutual struggle, even naming a prominent hill after Bejah Dervish “who has proved himself a splendid fellow and an excellent camel man” (Wells 1896: n.p.). Long after the expedition, Wells and Bejah continued to attract media attention for their exploits—and for their unlikely, enduring friendship. Bejah’s pride in his participation is demonstrated by the many occasions he displayed a treasured possession: a compass inscribed “Calvert Expedition, Bejah, 24/5/69” (News 1948; Sunday Mail 1950; Advertiser 1957). Moreover, many cameleers, like Bejah Dervish, chose to remain in Australia. For example, Abdul Khalick (b. Karachi 1860 d. 1936) worked for Elder, Smith and Co. for 9 years and subsequently spent 10 years working as a cameleer in Hergott Springs, 25 years in Broken Hill and Wilcannia, and 13 years at Oodnadatta.

European financiers and explorers alike entered into partnerships with cameleers, such as David Lindsay and camel merchant Mahmoud Hassan. Stuckey’s consignment from Karachi owed its success to the local merchant Morad Khan. Many cameleers established their own successful businesses. Bejah Dervish and Moosha Balooch supplied camels for the Madigan and Horn expeditions, respectively. In 1888, Faiz Mahomet (b. 1846 or 1848), previously Elder’s jemadar (camel foreman), received a loan of £1000 from Elder, Smith and Co. to establish his own business in partnership with his brother Tagh. They made their fortunes primarily from a significant contract to deliver supplies to Central Australian telegraph stations and later in the Western Australian goldfields near Coolgardie. These merchants, formerly contracted as indentured labourers, imported significant numbers of camels and established their own contracts with cameleers to conduct work in Australia. In 1893, Jumma Khan imported 400 camels and approximately 50 cameleers. Hassmoul Mouchand imported 389 camels in 1895. According to Stevens, Abdul Wade (also known as Wahid, 1866–1928) reputedly landed 750 camels at Port Augusta, South Australia, in 1 year in the late 1890s (Stevens 2005), by which time the camel-driving business was dominated by Muslim entrepreneurs (Jones and Kenny 2010); coinciding with the formation of inland settlements and the foundation of the Adelaide Mosque.

In addition to their contribution to the discovery and exploration of the Australian interior, some cameleers went on to successful careers in transportation and haulage or participated in the construction of the railways and the telegraph lines that stitched the nation together. Over time, the sites where the cameleers encamped attracted “Afghan” merchants, drapers, saddle-makers and imams, whose servicing of this peripatetic community led to their emplacement in Australia’s desert interior as part of the inexorable process of territorial expansion (Scriver 2004). Although the number of cameleers was low compared with the number of European and Chinese immigrants (Stevens 2002: 167), the nature and scale of their pioneering activities were extraordinary.

Territorial markers in the settler-colonial city of Adelaide

This inland economy was inextricably tied to the fortunes of the settler-colonial city. While the wealth of Elder and other pioneers financed the construction of civic, religious and commercial buildings, camel merchants’ savings provided the critical funding for the Adelaide Mosque. The period of 1860–1880 coincided with the exponential growth of pastoralism and mining (MacDougall and Vines 2006); aided by exploration and enabled by the cameleers’ sustained contributions, it represented a significant period of growth and, specifically, building activity in Adelaide. Duryea’s panorama of 1865 depicts the stately mansions and places of prayer and thus provides a compelling document of the emerging territorialisation of colonial Adelaide’s urban space and hierarchical notions of belonging. The construction of a “white, civilised British space”, as Edmonds contends, is also apparent in the new places of worship, which serve, as eminent architectural historian Spiro Kostof argues, “as palpable images of the values and aspirations of the societies that produced them” (Kostof 1995: 19).

Duryea’s bird’s-eye view clearly depicts the territorial stamp of these parishes and offers a palpable image of the competitive values and aspirations of Adelaide’s largely Anglo-Saxon, Protestant pioneers. Towers, gables and spires punctuated the skyline of this colonial city, including those of Chalmers Church on North Terrace (1851), the Congregational Church on Hindmarsh Square (1861), the United Presbyterian Church (completed 1865), St Andrew’s Church of Scotland on Wakefield Street (1859) and the Methodist New Connection Church (1864), the highest spire until the Town Hall was built.Footnote11 Each church adopts the architectural vocabulary of the gothic revival style to emulate the architectural traditions favoured by different factions of the Protestant church, distinct from the classicism of Catholicism. Similarly, Elder’s private residence in the Mt Lofty Ranges, “Carminow”, built in the Scottish baronial style at the end of his life in 1885, recalls his provenance as well as materialising his noble pretensions that were shaped by his extraordinary landholdings in the outback.

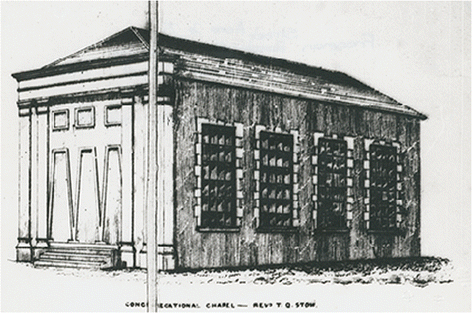

The delineation of ecclesiastical boundaries as one aspect of colonial spatial practices is epitomised in the construction of a high wall that separated the Pirie Street Wesleyan Methodist Church (1850) from the Stow Memorial Congregational Church (dedicated in 1867). These are the closest churches to Duryea’s vantage point at the Town Hall, and their central location highlights the wealth and status of these communities in the civic realm. The Stow Memorial Church provided a monumental place of worship. However, this material expression of the values and aspirations of the congregation, differentiated and distanced from the Wesleyans, had humbler origins. The first chapel was a temporary structure built of pine logs and reeds that served the basic function of congregation. This was replaced by the interim Freeman Street Congregational Chapel. This modest, unadorned structure was completed in 1840, to the design of colonial architect George Strickland Kingston (who also played a significant role in the design of Adelaide)—a building that in plan, massing and materiality, provided a near blueprint for the later Adelaide Mosque. This sequence of increasingly permanent places of worship tracks the funds at the disposal of the congregation and their increasingly confident expression of faith in this free province that was widely known for its tolerance of religious dissent (MacDougall and Vines 2006: 8).

While these exclusionary practices divided Adelaide’s Protestants, they can also be detected in the location of the first Catholic church of St Patrick (1845), which occupied a peripheral position on the city fringe in the vicinity of homes inhabited by recently arrived Irish Catholic immigrants, notably women and children following the potato famine that decimated the Irish population. It was distanced from the civic heart along with the flour mills, wheelwrights, brick kilns and other industries which are all visible in Duryea’s panorama. The periphery, and particularly the south-west corner of the city, was also the most likely place of residence for impoverished new immigrants who laboured to service the Anglo-Saxon elite.

In 1889, this south-west corner of the city was the site of the new mosque. In this context, the location of the Adelaide Mosque might be dismissed as a further example of the exclusionary spatial practices that polarised Adelaide’s Anglo-Saxon majority from the increasing number of immigrants who were differentiated on account of their class, race, gender and/or faith. The increasing fortunes of the cameleers, their agency in the construction of the mosque and the addition of the minarets first documented in The Critic, 17 August 1904, are indicative of the increasing confidence of this small community in the face of ongoing discrimination and ostracism shortly after the implementation of the Immigration Restriction Act imposed in 1901 (also known as the White Australia Policy). The mosque addressed the needs of the community and, in time, served as a palpable image of the values and aspirations—the “cultural capital”—of this ethnically diverse community that was united by its faith and the collective pioneering role in Australia.

Building identity: needs and aspirations

The funds for the mosques in Adelaide (Figs. 11 and 12) and Perth were primarily sourced from “Afghans” based in remote settlements.Footnote12 Detailed records exist that list the names of individual cameleers and merchants who contributed funds to the Perth Mosque, particularly those working in the Western Australian goldfields, which were collected by Faiz Mahomet. Contributions by Beltana cameleers are also recorded despite the distance of more than 2600 km—a testament to the inland communication network that the cameleers pioneered. These records, including the purchase of land for £680 in the heart of Perth, can be attributed to the erudition of Muhammad Hasan Musakhan, a Tarin Afghan of Sindh (and nephew of Morad Khan, who assisted Stuckey in Karachi), who was the founder (1904), treasurer (1906) and secretary of the mosque. Musakhan was educated at the universities of Karachi and Bombay; he then worked as a schoolteacher in India and a bookseller in Perth. He knew English, Pushto, Urdu, Persian, Sindhi and a “little Arabic” (Jones and Kenny 2010). In 1932, the year he visited Adelaide, he prepared a little-known pamphlet, funded by Adelaide philanthropist and herbalist Mahomet Allum, that documents the early history of Islam in Australia and is entitled The History of Islamism in Australia from 1863 to 1932 (Musakhan 1932).

Fig. 11

Little Gilbert Street Mosque (Adelaide Mosque), 1928. State Library of South Australia B21920. (No known copyright restrictions)

Full size image

Fig. 12

Adelaide Mosque. (Photograph by author, 2006)

Full size image

No such records have emerged to date that detail the specific source of funds for the Adelaide Mosque, but the origins of the mosque can be traced to two individuals: Haji Mullah Merban (1801–1897) and Abdul Wahid (1866–1928). However, it can be assumed that the funds to acquire the land and build the mosque derived from a similar, collective contribution. The Tarin Afghan Hadji Mullah Merban inspired the construction of the Adelaide Mosque and purchased the land. As one of the earliest cameleers to arrive in Australia, Merban, who worked on the supply teams for the Overland Telegraph Line, had emerged as a respected religious leader. Upon his retirement, he was appointed as the first caretaker of the Adelaide Mosque before living in Coolgardie between 1894 and 1897.Footnote13 Jones identifies the wealthy camel merchant Abdul Wahid, a former Ghilzai tribesman, as the builder and trustee of the Adelaide Mosque (Jones and Kenny 2010: 168). Although he is initially recorded as working with Faiz and Tagh Mahomet in 1892, he soon began work for the Bourke Carrying Company in New South Wales, which primarily serviced the mining industry in the wider region, and he was appointed manager and overseer in 1895 (Stevens 2005). His wealth was enhanced by his grazing properties, camel breeding, salt harvesting and haulage. His business transactions, including purchase of the desirable Northwood House designed by colonial architect Edmund Blacket on Lane Cove River in Sydney, were enabled by his fluency in English, and in 1902, shortly after assertion of the Immigration Restriction Act, he was naturalised. He was well known for his European style of dress, which distinguished him from other “Afghans” in Australia, his success in horse racing and his (partially successful) efforts to circulate in European social circles.

Local respect for Merban and Wahid may have assisted their efforts to purchase land for the mosque. While the cameleers were ostracised from “white civilised British space” (which is well recognised in previous studies), the acquisition of the land coincided with a significant economic recession in Adelaide. Agricultural development, in particular, had led to a boom period between 1870 and 1882 (MacDougall and Vines 2006). However, the drought of 1880 brought an end to this rapid growth and coincided with the demise of the intensive building activity between 1860 and 1880, which is evident in Duryea’s panorama, and a lingering depression. In this context, when there was a pressing need to fill the city coffers, the plans for the Adelaide Mosque were approved in 1887; would land have been sold or plans approved without the drought? The building was erected between 1888 and 1889, costing the cameleers over £450 (Observer 1901).

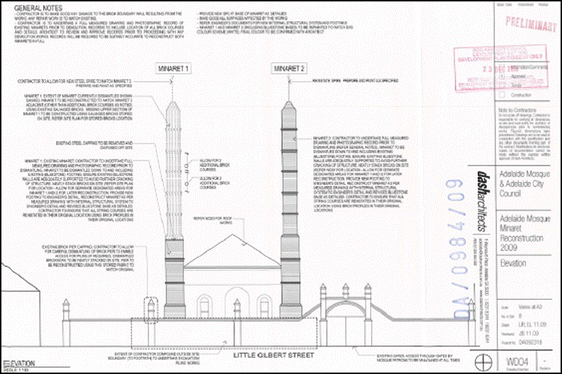

A comparison of the Adelaide Mosque with contemporary neighbouring dwellings reveals that the mosque was a modest addition to the existing urban fabric. The construction techniques parallel established modes of construction. Indeed, Jensen and Jensen include a photo of the mosque with buildings constructed 20 years prior; however, no further details are provided in this “definitive chronicle” (1980: 467). The typical construction comprises local bluestone from Mount Lofty Ranges laid in random coursework, tuck-pointed clay bricks and corrugated galvanised iron roofing (Pikusa 1986). The original building was a rectangle of undecorated stone that remained unpainted until 1891. Wrought-iron lacework, a typical embellishment of colonial verandas, was still evident in 1962 (SLSA B69987). The floor was constructed of concrete (Observer 4 July 1901). Comparison of Freeman Street Congregational Church (Fig. 13), mentioned earlier and visible in Duryea’s panorama, with architectural drawings prepared for the Adelaide Mosque as part of the reconstruction of the western minarets in 2009 (DASH Architects 2009; Fig. 14) reveals a striking similarity between the two buildings; the comparable height is the only aspect that would have distinguished the mosque in its single-storey context. Comparison with the latter, designed by Kingston, highlights the specialised knowledge required for the design, despite its modest scale and construction. Given these similarities, it is unlikely the cameleers built the mosque. It is likely that they engaged local builders who used established building technologies and materials. The immediate priority for the patrons of the Adelaide Mosque was to create a place that served the needs of the community—a dormant form activated through spatial practices and narratives of belonging—rather than symbolic and visual expressions of identity.

Fig. 13

Freeman Street, Congregational Chapel. Copied from Kingston's map of Adelaide, 1842. State Library of South Australia B15987. (No known copyright restrictions)

Full size image

Fig. 14

Elevation of Adelaide Mosque showing the reconstruction of the minarets due to structural instability, WD04. DASH Architects 2009. (Reproduced with permission from Jason Schulz, Director of DASH Architects)

Full size image

Early descriptions of the mosque, prior to the construction of the minarets or the wall, reveal that it was unobtrusive in the area. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the mosque was recorded as “an unpretentious building in stone and brick, 37 ft by 35 ft and 18 ft high” (Observer 4 July 1901). In addition, the author states that “providing sufficient money can be raised a dome will be erected on the south side” (Observer 4 July 1901). The dome was never built; however, the intent hints at the aspirations of the community to make a visual statement in the city. Inside, non-Muslim visitors remarked on the lack of decoration and furniture (Observer 1901; Advertiser 1903). Moreover, “to the visitor the interior of the mosque is disappointing. There is nothing in the building which calls for admiration. Its architectural pretensions are practically non-existent” (Advertiser 1903). Therefore, at the time of its construction, the mosque was not a site of controversy. Its purpose was to serve the needs of the community for daily prayer. The layout of the Adelaide Mosque recalls the simplicity of the first mosque—the Prophet Muhammad’s own house in Medina—where the Muslim community gathered in his courtyard (Rabbatt 2002). Unlike other religious architecture, the mosque does not have a predetermined building typology. Few architectural features differentiate the place of prayer. A niche, or mihrab, denotes the direction of Mecca in every mosque (in this case, the qibla is west, although many mosques are oriented north-west in Australia). Obligatory ablution precedes prayers and running water is crucial for this purpose. In Australia, despite the scarcity of water, mosques in the bush and the city contain this facility. In monumental Islamic mosques, ablution is performed at a fountain in the courtyard. In the Adelaide Mosque, a large cistern with running water served this purpose. The scale of the building is small, blending with the neighbouring structures of the period. Tectonically anonymous, the mosque did not initially constitute an overt affirmation of self-identity.

Fourteen years after its construction, four minarets were added, costing £500 in total (Advertiser 1903). The addition of the minarets might be interpreted as an overt message of Islam in the urban context—particularly in the context of Federation and the Immigration Restriction Act, which placed restrictions not only on immigration but also on the mobility of non-European peoples within Australia and, for the cameleers, compromised the freedom to travel back and forth between Australia and the Indian subcontinent. However, the earlier intent to construct a dome indicates the cameleers’ pre-existing desire to distinguish their place of prayer. The construction of the minarets could just as easily be interpreted as a natural progression when the necessary funds accrued. As in the case of the structure of the prayer hall, specialised building skills would have been essential to the construction of the minarets. The minarets were erected using English bond brick and filled with a masonry core. The construction technology is identical to the type of construction of local chimneys and incinerators that can be seen in Duryea’s panorama (although the minarets were not hollow nor used for adhan). The ironwork surmounting the minarets has been attributed to John Lockett of Logan Street (Jolly 2005). Thus, even the most explicit material expression of identity is also a product of engagement with the local builders and craftsmen.

A further territorial marker, the extant brick wall, which was built in 1908, may be interpreted as a means to distance the Muslim faithful from the surrounding neighbourhood. Imam Shah’s name appears on an advertisement as a contact for building tenders for the said wall (Advertiser 1908). However, this may also be interpreted as a practical response to security following the theft of items in 1906, identified as the belongings of Abdul Wahid, at the time that Jaffa Solomon (a Jewish man, brought up as a Mohammaden; Jones and Kenny 2010: 180) was caretaker of the Mosque (Advertiser 1906).

The “Afghan” community was proud of its hybrid mosque, which articulated the needs of the community in a local architectural vocabulary. It was also a valued expression of the international profile of “Afghans”, the majority of whom maintained strong ties with their families and their homeland throughout their contracts. In 1915, the mosque was featured in an international Afghan journal. The cost of the mosque was exaggerated (£3000). We also learn that funding was raised for a madrasa to be established near the mosque (Stevens 2002). Although this was not realised, it indicates that religious teaching was a further function of the mosque.

In this light, the mosque was a locus for community life, prayer, education and gathering. Further photographic evidence and archived newspapers provide evidence that the Adelaide Mosque was also a meeting place for the cameleers. Those who came to the city for business, for a holiday (like the cameleer Tauseef in 1910) or for health-related purposes could board at the cottage. After 1890, retired Afghan men are recorded living in the vicinity (Adelaide Observer 1891). In the 1890s, a congregation of 100 people is recorded. However, numbers dwindled to 30 in 1903. Afghan merchants are recorded living in this area in 1908 (Jolly 2005). Afghans travelled back and forth between the outback periphery and this urban centre. For example, successful cameleer Gool Mahomet, the mosque’s major benefactor between the 1930s and 1940s, stayed at the mosque before his final, intended, return to Kabul. He died at the mosque just 2 weeks before he was due to sail on the Himalaya.

At the age of 85, Bejah, the Afghan hero of the Calvert Expedition, travelled from his home of Marree, to attend Gool Mahomet’s funeral at the mosque. His visit was observed in the Adelaide Sunday Mail (1950). While the patronising tone of these articles cannot be dismissed, this entry is indicative of ongoing public interest in the cameleer’s life (Sunday Mail 1953). In 1948, a visit to “his old friend Mr McNamara”, former surveyor-general of South Australia, is recorded in the News (1948). At this time, Bejah was one of only five surviving Afghans in Marree. His final visit to Adelaide, at an estimated age of 100, was front-page news—along with the Queen of England’s visit—in 1954 (Advertiser 1954) .

Another cameleer identified with the mosque captured Adelaide’s popular imagination. Mahomet Allum (1858?–1964), the “miraculous” herbalist and philanthropist of Sturt Street, lived in the vicinity of the Adelaide Mosque (Advertiser 1964). As a healer, Allum proclaimed his faith to the community in numerous popular advertisements. With the assistance of his wife, former patient Effie Schwardt, he wrote letters to the press and published pamphlets on Islam, the Koran, illness and his healing powers (Hankel 1979b).

The existence of this minority group in Adelaide challenged European settlers who were unfamiliar with the religious and social customs of the cameleers and their rules of etiquette. By 1890, the mosque was commonly known as the “Afghan Chapel”. Non-Muslim perceptions of the Afghan community were mostly negative. The children of Sturt Street were frightened of Mahomet Allum and identified him with the strange minarets of the mosque. They believed “if you looked him straight in the eyes you would be strung up by the neck atop” a minaret (Jolly 2005). In this context, Mahomet Allum attenuated his difference, styling himself as Father Christmas. He declared that in Australia “the best known Daddy Xmas is the stately mannered beturbaned healer of human ills, Mahomet Allum of Sturt Street Adelaide” (Allum 1933). He further proclaimed that his services transcended cultural and religious difference (Allum 1930).

Allum’s success irked the Adelaide medical profession. He was charged and fined for posing as a medical practitioner on several occasions. In 1934, he prepared to leave Adelaide, much to the consternation of his supporters, who petitioned for him to stay. Further, respected community figures, including Detective Correll of C.I. Branch, testified to his healing powers (Correll 1930). Loved or hated, Mahomet Allum was Adelaide’s most well-known “Afghan”. The funeral procession on 23 March 1964 from the Adelaide Mosque to Centennial Park Cemetery was over a mile long. Generous until his death, Allum’s estate, valued at £11,218, was primarily bequeathed to children’s institutions.

The jenazar was performed by Sallay Mahomet, another successful member of the Afghan community. Sallay and his father Gool Mahomet took on the role of mullahs at the mosque until the 1950s. In 1947, Sallay married an Australian woman, Iris, in two ceremonies: a Muslim-Afghan ritual at the Adelaide Mosque and a church ceremony. Sallay is notable as one of the few cameleers who made the successful transition to truck driving while the majority returned to the Indian subcontinent. Restrictions on citizenship and a rising tide of racism in tandem with the White Australia Policy (which was not dismantled until 1973) made conditions intolerable. At this time, Sallay Mahomet was recognised as the spiritual leader of the “Afghan” community in Central Australia and Alice Springs. In this role, Sallay was invited to present the Whitlam government’s gift of camels to the King Khaled of Saudi Arabia in June 1975, to the surprise of a community who thought their heritage had been forgotten (Sydney Morning Herald Nov 1979).

Re-territorialisation through “cultural capital”

One might expect that this diplomatic gesture would improve national recognition of the cameleers. However, Arthur Earle, “a millionaire Queenslander from the Gold Coast, was annoyed when Australia’s Bicentennial planning for 1988 ignored the camel’s contribution to the nation’s history” (Westrip and Holroyde 2010: 191); no mention is made of the cameleers. Instead, efforts to inscribe the cameleers’ contributions in the national conscience and to acknowledge the “cultural capital” in a substantial way are evident in the discipline of architecture and urban design. Civic markers installed on North Terrace for the Jubilee in 1986 record Bejah and Elder (Figs. 15 and 16).

Fig. 15

Plaque commemorating cameleer Bejah Dervish, Jubilee Walkway, North Terrace, Adelaide, 1986. (Photograph by author)

Full size image

Fig. 16

Plaque commemorating Sir Thomas Elder, Jubilee Walkway, North Terrace, Adelaide, 1986. (Photograph by author)

Full size image

However, the most significant step in the process of local re-territorialisation is evident in the reconstruction of the mosque’s minarets. While this initiative was prompted by pragmatic concerns due to their instability, the project provides evidence of collaboration that disrupts fixed hierarchical notions of belonging or exclusionary spatial practices. In the built environment disciplines, recognition of the cameleers’ legacy and the “cultural capital” of Adelaide’s Muslim community is manifest in the heritage status attributed to the building (Register of City of Adelaide Heritage Items; State Heritage Register ID 10947; Register of the National Trust South Australia ID 1284). Bond and Ramsay identified the “Mohammedan Mosque” as an item which is “essential to the heritage of Australia and which should be preserved” in 1978 (Bond and Ramsay 1978). Given this heritage status and the pragmatic need to ensure stability, the east and west minarets were rebuilt in 2000 and 2010. All showed signs of leaning due to the reactive soils and changes in the groundwater condition on site. Moreover, the minarets were not built to withstand earthquakes. After careful dismantling brick by brick, the construction of each new minaret rests on 4 × 127 mm diam. mini-piles, approximately 9000 mm deep, topped by a concrete cap. The caps support a steel reinforcing skeleton. The bricks were cleaned and reused to construct the shell or outer wall of the minarets and filled with concrete (Danvers Architects 2000; DASH Architects 2009). In the case of the latter project (west minarets), funding was not secured through the competitive National Heritage Investment Initiative grants program (2007–2008). However, funding support was derived through an alternative Federal Grant ($329,000AUD) under the Australian Government Jobs Fund and the Adelaide City Council’s Heritage Incentive Scheme ($52,000AUD), together with a loan to The Adelaide Mosque Islamic Society of South Australia ($40,000AUD) (Deed, Norman Waterhouse Lawyers, Adelaide City Council Archives).

This support within Adelaide City Council is further evident in the construction of an abstract memorial to the cameleers in Whitmore Square, in the vicinity of the mosque, by Thylacine Art Projects in 2005 (Bartsch 2006). This project, which involved a community consultation project to develop the scheme, coincided with Bridget Jolly’s history of the south-west corner of the city which places much emphasis on the “cultural capital” of the neighbourhood’s Muslim community (2005). This study was followed shortly afterwards by the promotion of the mosque during South Australia History Week (20–28 May 2006) in an initiative that was supported by the Government of South Australia, History Trust of South Australia, Department for Environment and Heritage, Adelaide City Council, University of Adelaide and the National Trust of South Australia. Considered together, these joint initiatives displace fixed hierarchical notions of who belongs and who does not at the scale of the neighbourhood.

In conclusion, Townsend Duryea’s bird’s-eye view of Adelaide in 1865 reveals a prime example of a settler-colonial city. While the imposition of the city’s plan dispossessed the Indigenous owners and decimated the pre-European vegetation, Adelaide’s economic boom periods—fuelled by the region’s lucrative mineral resources and agricultural and pastoral riches—coincided with aggressive property speculation. This wealth established Adelaide’s place as a node in active trans-imperial networks, but the construction of monumental places of worship in this new province, famed for its tolerance of religious dissent, demarcated a white, civilised British, primarily Protestant, space. Moreover, the development of the city and the emergence of distinct zones for commerce and industry as well as residential areas spatialised a tangible hierarchy of belonging in relation to status, faith, race and wealth.

In this context, the location of the Adelaide Mosque in the south-west corner of the city might be dismissed as a further example of the ways in which minority groups were left with no choice but to inhabit the periphery, and certainly, the marginalisation, racism and ostracism that the majority of “Afghans” experienced must not be ignored. However, this examination of the foundation of the Adelaide Mosque in the city, the agency of the cameleers that provided the funds, their extraordinary contributions to the development of the inland economy and, by extension, the fortunes of the colonial city complicates the pattern of the settler-colonial city. It has revealed overlapping territories and intertwined histories that do not neatly map onto the model of centre and periphery that characterises the definition of settler-colonial cities or the majority of representations of “Afghans”—many of whom were British subjects—in Australia. Thus, the Adelaide Mosque emerges as a modest but vital space to serve the needs of the Muslim faithful in the city. In time, further funding enabled an increasingly confident expression of identity in the city through the construction of the minarets that differentiated this small community. Yet, even in this overt articulation of identity, the materialisation of all aspects of the buildings was a result of engagement at the level of the neighbourhood through building contracts, tenders and the continuity of local, pragmatic building practices that reinvented local chimneys as minarets. Coupled with the activities of merchants, hawkers or herbalists, it is difficult to delimit the territory of one of Australia’s earliest Muslim communities. Reiterating Regina Ganter’s identification of the fantasy of a white Australian history and the deep histories of contact, the Adelaide Mosque serves as a palpable image of the values and aspirations of Australia’s Muslim pioneers and highlights the place of Islam in Australian history—and which continues to play a vital role in the process of re-territorialisation in recent years—which must not be neglected amid claims for identity and citizenship today.

Notes

1.

The Duryea panorama can be viewed at http://www.fusion.com.au/duryea/html/pano.html. This interactive multimedia version of the panorama is a joint venture by the History Trust of South Australia, Fusion Digital and Adelaide City Council.

2.

Drawings of the Shah Jahan Mosque in Woking, Surrey, UK, were prepared by the eminent orientalist architect William Chambers in consultation with the patron, linguist Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner. The monumental mosque in Paris was not built until 1922 (Maussen 2007).

3.

Duryea was a prolific photographer who established his business in the commercial heart of Adelaide on the corner of King William and Grenfell Streets in 1855. His studios were destroyed by fire in 1875, and it is estimated that over 50,000 negatives were destroyed (Noye 1972).

4.

Australia’s major exports continue to derive from natural resources: iron ore and concentrates, coal, gold, natural gas and petroleum. The major export destinations are China, Japan, The Republic of Korea and India. Australia Fact Sheet http://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/fs/aust.pdf

5.

Popular interest in the cultural heritage of the cameleers and the physical traces of Islam in colonial Australia is evident in the reception of the highly successful exhibition titled Australia’s Muslim Cameleers, which has travelled nationally and internationally since it was launched in 2007. The exhibition, curated by Dr. Philip Jones, senior curator of anthropology at the South Australian Museum, led to the publication, with Anna Kenny, of a rich pictorial history of the cameleers entitled Australia’s Muslim Pioneers: Pioneers of the Inland, 1860s–1930s (2007) and an interactive website in 2011 (www.cameleers.net).

6.

These studies are significant additions to the early studies of the role of camels in exploration and expansion (Barker 1964; McKnight 1969) and studies focusing on the cameleers (Farwell 1961; Rajkowski 1987; Westrip and Holroyde 2010).

7.

Before the arrival of Muslim cameleers (and European settlers), Muslim Macassan fishermen from Sulawesi are known to have travelled regularly to northern Australia in search of trepang (a type of sea cucumber valued for its aphrodisiacal properties), and their visits were recorded in images by Indigenous peoples and in British records after 1762.

8.

The Australian Research Council Linkage Project, mentioned above, will examine these settlements from the perspective of architecture and urban planning. Based on the earlier work of Dr. Philip Jones with Anna Kenny (2010; Jones 2011), we propose that Afghan settlement was not self-contained, homogeneous and independent from other inland settlements, rather, they formed an integral part.

9.

Notes from a Pocket Journal of a Trip Up the River Murray in 1856 (1893); Narrative of a Tour in Palestine in 1857 (1894); Travels in Algeria in 1860 (1894); Notes from a Pocket Journal of Rambles in Spain in 1860 (1894).

10.

A map of this expedition entitled Map showing the routes travelled and discoveries made by the exploring expeditions equipped by Thomas Elder and under the command of Ernest Giles [cartographic material]: between the years 1872–6 can be viewed online at the National Library of Australia at http://nla.gov.au/nla.map-rm2902-1.

11.

All of these sites are readily viewed on the interactive panorama identified in fn 1.

12.

Another early mosque was built in Brisbane in 1909 although this mosque, built in the vernacular style of tropical Queensland, is beyond the scope of this paper.

13.

Subsequent caretakers in this period included Muhammad Drim (b. circa 1867 d.1947), in Merban’s absence (Brisbane Courier 1893: 4), and Goolam Rasool (c. 1864–1941, who had worked for Elder at Beltana), appointed by Abdul Wahid to “manage and control the said Mosque” (Advertiser 1919: 1).

References

Allum, M. (1930). Mahomet Allum advertisement. State Library of South Australia, B52941.

Allum, M. (1933). Santa Claus in Australia. Smith’s Weekly, December 23, 1933. State Library of South Australia, B52942

Barker, H. M. (1964). Camels and the outback. Melbourne: Pitman.

Google Scholar

Bartsch, K. (2006). Enigma of cultural representation in design practice. Place Architecture + Design + Placemaking, 2(2), 38–39.

Google Scholar

Bond, C., & Ramsay, H. (Eds.). (1978). Preserving historic Adelaide. Adelaide: Rigby.

Google Scholar

Bouma, G. (1994). Mosques and Muslim settlement in Australia. Canberra: Bureau of Immigration and Population Research. http://www.multiculturalaustralia.edu.au/doc/bimprmuslim_1.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec 2012.

City of Adelaide. (1990). Heritage Study Item No. 159, Adelaide Mosque File. Adelaide: Heritage South Australia.

Google Scholar

Correll. (1930). Testimonial by Detective Correll of C.I. Branch, Mahomet Allum testimonial. State Library of South Australia, B52940, Portrait Collection.

Danvers Architects. (2000). Adelaide Mosque: final project report. North Adelaide: Danvers Architects.

Google Scholar

DASH Architects. (2009). Adelaide Mosque minaret reconstruction. Working drawings. Adelaide City Council, Heritage Branch.

Deen, H. (n.d.). Uncommon lives: Muslim journeys. National Archives of Australia. http://uncommonlives.naa.gov.au. Accessed 7 Nov 2012.

Edgar, S. (1986). Lindsay, David (1856–1922). Australian dictionary of biography. http://adb.anu.edu.au. Accessed 26 Feb 2012.

Edmonds, P. (2010). Unpacking settler colonialism’s urban strategies: indigenous peoples in Victoria, British Colombia, and the transition to a settler-colonial city. Urban History Review/Revue d’histoire Urbaine. doi:10.7202/039671ar.

Google Scholar

Farwell, G. (1961). Vanishing Australians. Adelaide: Rigby.

Google Scholar

Ganter, R. (2008). Muslim Australians: the deep histories of contact. Journal of Australian Studies, 32(4), 481–492.

Article Google Scholar

Giles, E. (1964). Australia twice traversed. Adelaide: Libraries Board of South Australia.

Google Scholar

Green, L. (1972). Giles, Ernest (1835–1897). Australian dictionary of biography. http://adb.anu.edu.au. Accessed 26 Feb 2012.

Hankel, V. (1979a). Bejah Dervish (1862–1957). Australian dictionary of biography. http://adb.anu.edu.au. Accessed 7 Nov 2012.

Hankel, V. (1979b). Mahomet Allum (1858?–1964). Australian dictionary of biography. http://adb.anu.edu.au. Accessed 1 March 2013.

Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. (2003). IsmaE-Listen: national consultations on eliminating prejudice against Arab and Muslim Australians. Canberra: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

Google Scholar

Humphrey, M. (2010). Securitisation, social inclusion and Muslims in Australia. In S. Yasmeen (Ed.), Muslims in Australia: the dynamics of exclusion and inclusion (pp. 56–78). Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Google Scholar

Jensen, E., & Jensen, R. (1980). Colonial Adelaide architecture: a definitive chronicle of development, 1836–1890 and the social history of the time. Adelaide: Rigby.

Google Scholar

Jolly, B. (2005). Historic south west corner: Adelaide, South Australia. The City of Adelaide. http://www.sahistorians.org.au/175/bm.doc/sw-historic-a5-booklet-2.pdf. Accessed 3 March 2013.

Jones, M. (Ed.). (1993). An Australian pilgrimage: Muslims in Australia from the seventeenth century to the present. Melbourne: Victoria Press with the Museum of Victoria.

Google Scholar

Jones, P. (2011). Australia’s Muslim cameleers, South Australian Museum. http://www.cameleers.net. Accessed 7 Nov 2012.

Jones, P., & Kenny, A. (2010). Australia’s Muslim cameleers: pioneers of the inland, 1860s–1930s. Kent Town: Wakefield Press (Original work published 2007).

Google Scholar

Kabir, N. (1993). The first Muslims in Australia: the Afghan community. In M. J. Jones (Ed.), An Australian pilgrimage: Muslims in Australia from the seventeenth century to the present (Chapter 2). Melbourne: Victoria Press with the Museum of Victoria.

Google Scholar

Kabir, N. (2006). Representation of Islam and Muslims in the Australian media, 2001–2005. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 26(3), 313–328.

Article Google Scholar

Kabir, N. (2007). Muslims in Australia: the double edge of terrorism. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 33(8), 1277–1297.

Article Google Scholar

Kostof, S. (1995). A history of architecture: settings and rituals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kraehenbuehl, D. N. (1996). Pre-European vegetation of Adelaide: a survey from the Gawler River to Hallett Cove. Adelaide: Nature Conservation Society of South Australia.

Google Scholar

Leach, N. (2005). Belonging: towards a theory of identification with space. In Habitus: a sense of place, edited by Jean Hillier and Emma Rooksby, Chapter 15. Aldershot: Ashgate.

MacDougall, K., & Vines, L. (2006). The City of Adelaide: a thematic history. http://www.adelaidecitycouncil.com/assets/acc/Council/docs/city_of_adelaide_thematic_history.pdf. Accessed 10 Feb 2013.

Maussen, M. (2007). Islamic presence and mosque establishment in France: colonialism, arrangements for guestworkers and citizenship. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. doi:10.1080/13691830701432889.

Google Scholar

McKnight, T. L. (1969). The Camel in Australia. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Musakhan, H. M. (1932). The history of Islamism in Australia from 1863–1932. Adelaide: Mahomet Allum.

Google Scholar

Northcote, J., Hancock, P., & Casimiro, S. (2006). Breaking the isolation cycle: the experience of Muslim refugee women in Australia. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 15(2), 177–199.

Article Google Scholar

Noye, R. (1972). Duryea, Townsend (1823–1888). Australian dictionary of biography. http://adb.anu.edu.au. Accessed 7 Nov 2012.

Parkin, L. (1986). Madigan, Cecil Thomas (1889–1947). Australian dictionary of biography. http://adb.anu.edu.au. Accessed 7 Nov 2012.

Pikusa, S. (1986). The Adelaide House, 1836–1901: the evolution of principal dwelling types. Adelaide: Wakefield Press.

Google Scholar

Rabbatt, N. (2002). In the beginning was the house: on the image of two noble sanctuaries of Islam. Thresholds, 25, 56–59.

Google Scholar

Rajkowski, P. (1987). In the tracks of the camelmen: outback Australia’s most exotic pioneers. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

Google Scholar

Saeed, A. (2003). Islam in Australia. Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Google Scholar

Said, E. (1994). Culture and imperialism. London: Vintage.

Google Scholar

Saniotis, A. (2004). Embodying ambivalence: Muslim Australians as ‘other’. Journal of Australian Studies, 28(82), 49–59.

Article Google Scholar

Scriver, P. (2004). Mosques, ghantowns and cameleers in the settlement history of colonial Australia. Fabrications, 13(1), 19–41.

Article Google Scholar

Steele C. (1990). Wells, Lawrence Allen (1860–1938). Australian dictionary of biography. http://adb.anu.edu.au. Accessed 22 Feb 2013.