Survivor recalls 'unwanted' Chinese liberated by Australia after World War II

Survivor recalls 'unwanted' Chinese liberated by Australia after World War II

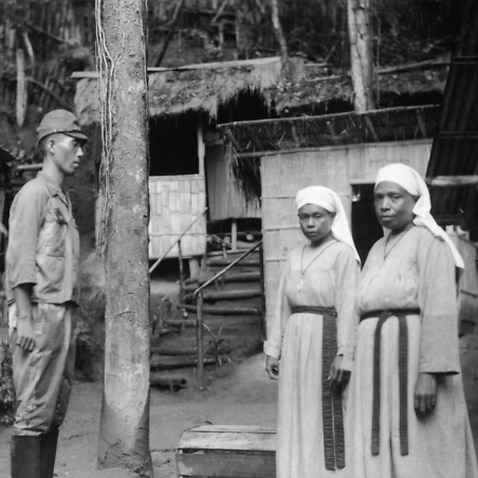

Children celebrate freedom after Australian soldiers liberate the Ratongor labour camp in September 1945. Source: Australian War Memorial

A few photos and a 90-second black and white film in the Australia War Memorial archive, a cooking pot made from a crashed US fighter plane and the memories of a few, very elderly survivors are all that remains from a shameful episode during the Second World War.

UPDATEDUPDATED 5 HOURS AGO

BY STEFAN ARMBRUSTER

SHARE

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Seventy-five years ago, Australian forces liberated hundreds of ethnic Chinese prisoners of a Japanese civilian forced labour camp called Ratongor in New Guinea at the end of the Second World War.

They had been left behind after Australia evacuated Europeans ahead of the Japanese invasion, and they survived more than three years of brutality in the then-occupied Australian territory.

But their story is largely untold.

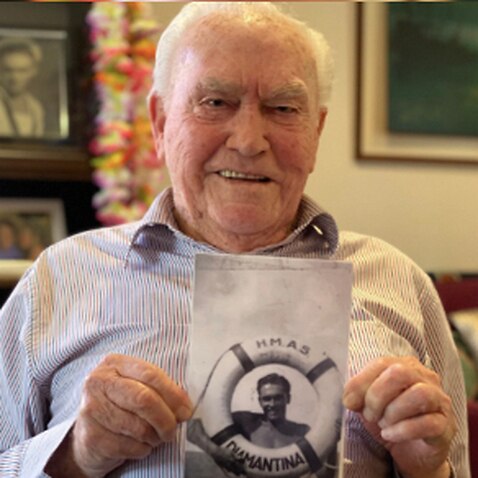

Tim Mak in Australian uniform after being recruited as an interpreter in 1945.

Stefan Armbruster/SBS News

The footage from September 1945 when Australian forces liberated Ratongor, near Rabaul in New Britain, shows Chinese children celebrating freedom and receiving rations from soldiers.

“Everybody's happy. Yes, everybody happy, celebrating. The Australians, they were good, they were giving them food and everything,” 96-year-old Tim Mak, one of about 850 people held in the camp for ethnic Chinese captives, told SBS News.

“That’s me,” he said, watching the film and pointing to his 21-year-old self.

READ MORE

The forgotten story of the civilian prisoners of war who survived in the Pacific

Sitting with Mr Mak at his Brisbane home is his nephew Geoff Hui, whose parents were also interned.

“And that’s my mum, that’s my sister born in March 1945, that’s my aunty Diana - she’s still here in Brisbane,” he said.

00:00 / 01:42

Memories come flooding back and for Mr Hui, the realisation of untold history.

“History depends on who writes it and nobody has written it from our point of view,” he said.

The Chinese were brought to New Guinea in the late 1800s by German colonists. They remained in what was then known as Kaiser Wilhelmsland when at the the start of the First World War, it was taken over by Australia and became a protectorate.

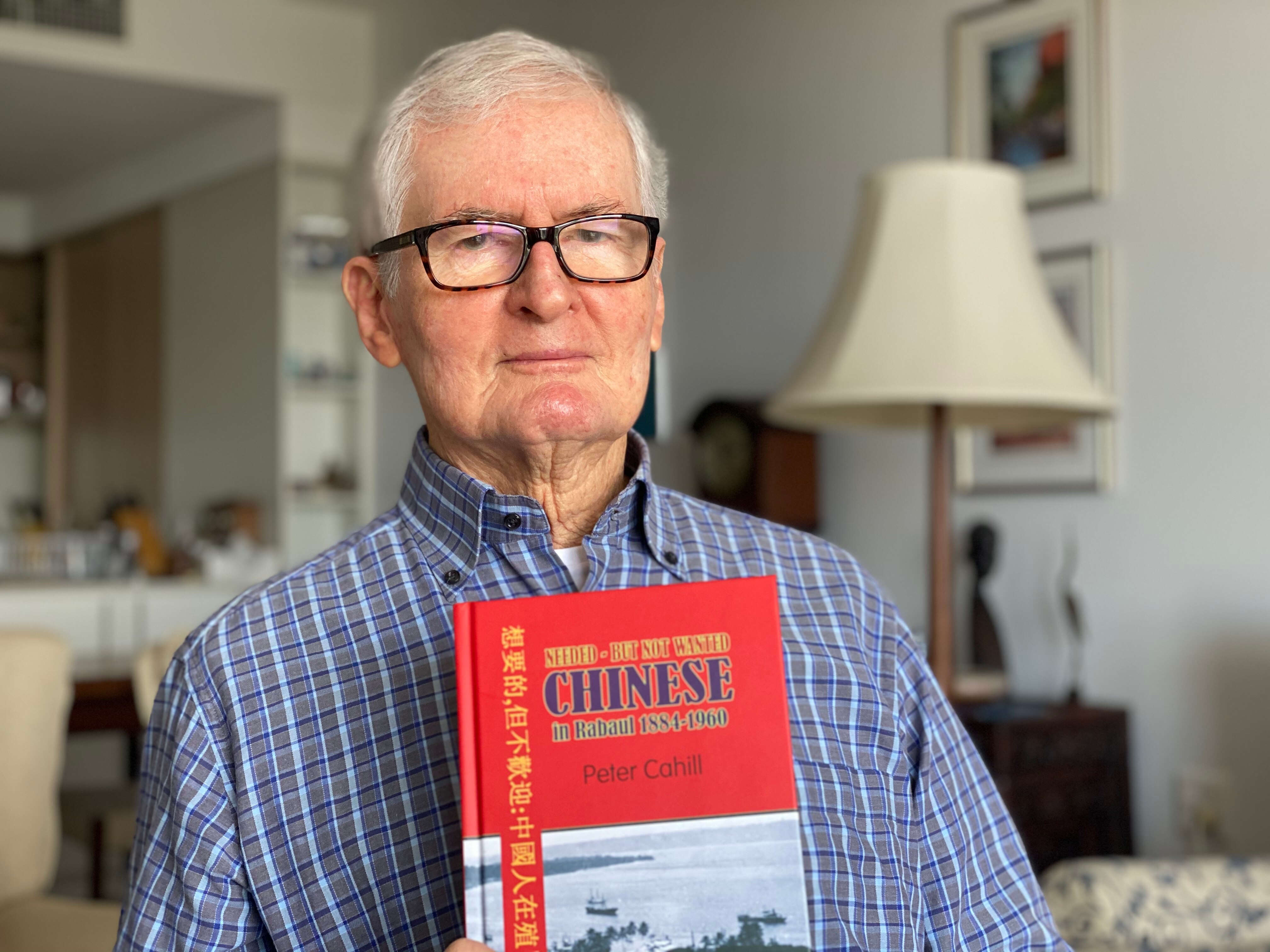

One of the very few books about the Chinese in New Guinea is by 85-year-old New Guinea-born Australian historian Dr Peter Cahill.

“It’s called Needed But Not Wanted. They were needed as labourers but not wanted because of the colour bar,” he told SBS News.

Historian Dr Peter Cahill author of "Needed But Not Wanted".

Stefan Armbruster/SBS News

“Australia inherited them but they weren’t a welcome inheritance because the Germans were sent back to Germany, and the Chinese stayed on and the Australians scratched their heads and said what are we going to do with this lot.”

Ahead of the Japanese advance in 1942, Australia only evacuated Europeans like Peter Cahill from New Guinea, but not the Chinese.

“Racism of course. The Australians tolerated them, but certainly didn’t welcome them,” said Dr Cahill.

The invasion of Rabaul marked one of Australia’s greatest defeats on home soil.

“Pretty close to the invasion time, the Japanese came and they bombed and they evacuated all Europeans citizens in a boat. We are left behind. Because at that time Australia doesn’t want Asians,” Mr Mak said.

“We were gutted.”

Chinese prisoners at Ratongor as Australian soldiers arrive in September 1945.

Australian War Memorial

Hundreds of Chinese civilians like Mr Mak were captured and they witnessed more than three years of Japanese depravity - executions, forced labour and rape.

“They don’t muck around, they shoot you,” he said.

“And everyday they were looking for woman, they want woman. What can you do? Stick with your family and survive.”

Mr Mak worked on the docks unloading supplies and others worked in gardens growing food for the Japanese.

READ MORE

80 years ago, Henry Lum Yip opened a grocers in Sydney. His grandkids still run it today

They gathered intelligence which his late brother collected and passed onto the Allies through a network of New Guineans and Australian coast-watchers in the hills above Rabaul.

“It was very dangerous work, if they found out the whole family would be gone. They don’t muck around,” he said.

They dug tunnels into hillsides as air raid shelters, sometimes coming under attack from Allied planes.

“One plane coming in very low, a US Corsair fighter, strafed the place and crashed right by the camp. We took the plane to pieces, we made shovels, anything we could make out of the plane.”

This includes a cooking pot, a heirloom that is still used at their family home in Port Moresby.

Cooking pot made in Ratongor from a crashed US Corsair fighter plane.

Supplied

The war is now a distant memory, and Mr Mak does not speak of it often. But he has not forgotten his time in Ratongor, or when the Australians arrived in 1945, “recruited” him and put him in uniform.

“As soon as they landed they went looking for an interpreter. I said what sort interpreter? And they just said get in the car and that’s it, they took me away,” he said.

“When war finished you just got to go get a job and you just gotta survive. We did survive.”

READ MORE

Australian veteran Bill McDonald recalls the moment he knew World War II was over, 75 years on

In 1954 Mr Mak was invited to meet Australian prime minister Sir Robert Menzies during a visit to Rabaul.

“I introduced myself, ‘My name is Mak’, and he said, 'Stop, stop. Where did you learn your English?'” Mr Mak laughed.

“This bloody school called Wesley College in Melbourne,” Mr Mak said he told Mr Menzies, to which the prime minister replied, “That’s where I went to school.”

“He called his number two and said, ‘Look after him, he’s one of my mates’.”

Tim Mak with his MBE awarded in 1975.

Supplied

In the years since the war Mr Mak has become a successful businessman and helped the Chinese community to rebuild.

Decades later Mr Mak was awarded an MBE for service to Papua New Guinea and was given Australian citizenship.

“I don’t think about these things,” said the 96-year-old retiree.

“I just think forward, always forward.”

No comments:

Post a Comment