The New Yorker

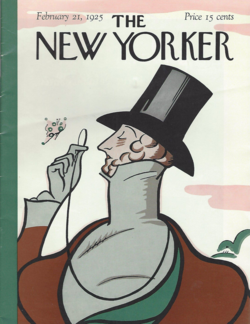

Cover of the first issue from February 21, 1925, featuring the figure of dandy Eustace Tilley, created by Rea Irvin[a] | |

| Editor | David Remnick |

|---|---|

| Categories |

|

| Frequency | 47 issues/year |

| Format | 77⁄8 by 103⁄4 inches (200 mm × 273 mm)[3] |

| Publisher | Condé Nast |

| Total circulation | 1,319,919[4] (Oct. 2025) |

| First issue | February 21, 1925 |

| Company | Advance Publications |

| Country | United States |

| Based in | New York City |

| Language | English |

| Website | www |

| ISSN | 0028-792X |

| OCLC | 320541675 |

The New Yorker is an American magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. It was founded on February 21, 1925, by Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, a reporter for The New York Times. Together with entrepreneur Raoul H. Fleischmann, they established the F-R Publishing Company and set up the magazine's first office in Manhattan. Ross remained the editor until his death in 1951, shaping the magazine's editorial tone and standards, such as its robust fact-checking operation, for which The New Yorker is widely recognized.[5]

Although its reviews and events listings often focused on the cultural life of New York City, The New Yorker gained a reputation for publishing serious essays, long-form journalism, well-regarded fiction, and humor for a national and international audience, including work by writers such as Truman Capote, Vladimir Nabokov, and Alice Munro. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the magazine adapted to the digital era, maintaining its traditional print operations while expanding its online presence, including making its archives available on the Internet and introducing a digital version of the magazine. David Remnick has been the editor of The New Yorker since 1998. Since 2004, The New Yorker has published endorsements in U.S. presidential elections.

The New Yorker is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues covering two-week spans. It is well known for its illustrated and often topical covers, such as View of the World from 9th Avenue,[6] its commentaries on popular culture and eccentric American culture, its attention to modern fiction by the inclusion of short stories and literary reviews, its rigorous fact checking and copy editing,[7][8] its investigative journalism and reporting on politics and social issues, and its single-panel cartoons reproduced throughout each issue. According to a 2012 Pew Research Center study, The New Yorker, along with The Atlantic and Harper's Magazine, ranked highest in college-educated readership among major American media outlets.[9] It has won eleven Pulitzer Prizes since 2014, the first year magazines became eligible for the prize.[10]

Overview and history

The New Yorker was founded by Harold Ross (1892–1951) and his wife Jane Grant (1892–1972), a New York Times reporter, and debuted on February 21, 1925. Ross wanted to create a sophisticated humor magazine that would be different from perceivably "corny" humor publications, such as Judge, where he had worked, or the old Life. Ross partnered with entrepreneur Raoul H. Fleischmann (who founded the General Baking Company)[11] to establish the F-R Publishing Company. The magazine's first offices were at 25 West 45th Street in Manhattan. Ross edited the magazine until his death in 1951. During the early, occasionally precarious years of its existence, the magazine prided itself on its cosmopolitan sophistication. Ross declared in a 1925 prospectus for the magazine: "It has announced that it is not edited for the old lady in Dubuque".[12]

Although the magazine never lost its touches of humor, it soon established itself as a preeminent forum for serious fiction, essays and journalism. Shortly after the end of World War II, John Hersey's essay Hiroshima filled an entire issue. The magazine has published short stories by many of the most respected writers of the 20th and 21st centuries, including Ann Beattie, Sally Benson, Maeve Brennan, Truman Capote, Rachel Carson, John Cheever, Roald Dahl, Mavis Gallant, Geoffrey Hellman, Ernest Hemingway, Stephen King, Ruth McKenney, John McNulty, Joseph Mitchell, Lorrie Moore, Alice Munro, Haruki Murakami, Vladimir Nabokov, John O'Hara, Dorothy Parker, S.J. Perelman, Philip Roth, George Saunders, J. D. Salinger, Irwin Shaw, James Thurber, John Updike, Eudora Welty, and E. B. White. Publication of Shirley Jackson's "The Lottery" drew more mail than any other story in the magazine's history.[13]

The nonfiction feature articles (usually the bulk of an issue) cover an eclectic array of topics. Subjects have included eccentric evangelist Creflo Dollar,[14] the different ways in which humans perceive the passage of time,[15] and Münchausen syndrome by proxy.[16]

The magazine is known for its editorial traditions. Under the rubric Profiles, it has published articles about prominent people such as Ernest Hemingway, Henry R. Luce, Marlon Brando, Hollywood restaurateur Michael Romanoff, magician Ricky Jay, and mathematicians David and Gregory Chudnovsky. Other enduring features have been "Goings on About Town", a listing of cultural and entertainment events in New York, and "The Talk of the Town", a feuilleton or miscellany of brief pieces—frequently humorous, whimsical, or eccentric vignettes of life in New York—in a breezily light style, although latterly the section often begins with a serious commentary. For many years, newspaper snippets containing amusing errors, unintended meanings or badly mixed metaphors ("Block That Metaphor") have been used as filler items, accompanied by a witty retort. There is no masthead listing the editors and staff. Despite some changes, the magazine has kept much of its traditional appearance over the decades in typography, layout, covers, and artwork. The magazine was acquired by Advance Publications, the media company owned by Samuel Irving Newhouse Jr, in 1985,[17] for $200 million when it was earning less than $6 million a year.[18]

Ross was succeeded as editor by William Shawn (1951–1987), followed by Robert Gottlieb (1987–1992) and Tina Brown (1992–1998). The current editor of The New Yorker is David Remnick, who succeeded Brown in July 1998.[19]

Among the important nonfiction authors who began writing for the magazine during Shawn's editorship were Dwight Macdonald, Kenneth Tynan, and Hannah Arendt, whose Eichmann in Jerusalem reportage appeared in the magazine,[20] before it was published as a book.[21]

Brown's tenure attracted more controversy than Gottlieb's or even Shawn's, due to her high profile (Shawn, by contrast, had been an extremely shy, introverted figure), and to the changes she made to a magazine with a similar look for the previous half-century. She introduced color to the editorial pages (several years before The New York Times) and included photography, with less type on each page and a generally more modern layout. More substantively, she increased the coverage of current events and topics such as celebrities and business tycoons, and placed short pieces throughout "Goings on About Town", including a racy column about nightlife in Manhattan.

Since the late 1990s, The New Yorker has used the Internet to publish current and archived material, and maintains a website with some content from the current issue (plus exclusive web-only content). Subscribers have access to the full current issue online and a complete archive of back issues viewable as they were originally printed. In addition, The New Yorker's cartoons are available for purchase online. In 2014, The New Yorker opened up online access to its archive, expanded its plans to run an ambitious website, and launched a paywalled subscription model. Web editor Nicholas Thompson said, "What we're trying to do is to make a website that is to the Internet what the magazine is to all other magazines".[22]

The magazine's editorial staff unionized in 2018 and The New Yorker Union signed its first collective bargaining agreement in 2021.[23]

Influence and significance

The New Yorker influenced a number of similar magazines, including The Brooklynite (1926 to 1930), The Chicagoan (1926 to 1935), and Paris's The Boulevardier (1927 to 1932).[24][25][26]

Kurt Vonnegut said that The New Yorker has been an effective instrument for getting a large audience to appreciate modern literature.[27] Tom Wolfe wrote of the magazine: "The New Yorker style was one of leisurely meandering understatement, droll when in the humorous mode, tautological and litotical when in the serious mode, constantly amplified, qualified, adumbrated upon, nuanced and renuanced, until the magazine's pale-gray pages became High Baroque triumphs of the relative clause and appository modifier".[28]

Joseph Rosenblum, reviewing Ben Yagoda's About Town, a history of the magazine from 1925 to 1985, wrote, "The New Yorker did create its own universe. As one longtime reader wrote to Yagoda, this was a place 'where Peter DeVries ... [sic] was forever lifting a glass of Piesporter, where Niccolò Tucci (in a plum velvet dinner jacket) flirted in Italian with Muriel Spark, where Nabokov sipped tawny port from a prismatic goblet (while a Red Admirable perched on his pinky), and where John Updike tripped over the master's Swiss shoes, excusing himself charmingly'".[29]

United States presidential election endorsements

On November 1, 2004, the magazine endorsed a presidential candidate for the first time, choosing Democratic nominee John Kerry over incumbent Republican George W. Bush.[30]

| Year | Endorsement | Result | Other major candidate(s) | Ref. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | John Kerry | Lost | George W. Bush | [31] | ||||||

| 2008 | Barack Obama | Won | John McCain | [32] | ||||||

| 2012 | Barack Obama | Won | Mitt Romney | [33] | ||||||

| 2016 | Hillary Clinton | Lost | Donald Trump | [34] | ||||||

| 2020 | Joe Biden | Won | Donald Trump | [35] | ||||||

| 2024 | Kamala Harris | Lost | Donald Trump | [36] | ||||||

Cartoons

The New Yorker has featured cartoons (usually gag cartoons) since it began publication in 1925. For years, its cartoon editor was Lee Lorenz, who first began cartooning in 1956 and became a New Yorker contract contributor in 1958.[37] After serving as the magazine's art editor from 1973 to 1993 (when he was replaced by Françoise Mouly), he continued in the position of cartoon editor until 1998. His book The Art of the New Yorker: 1925–1995 (Knopf, 1995) was the first comprehensive survey of all aspects of the magazine's graphics. In 1998, Robert Mankoff took over as cartoon editor and edited at least 14 collections of New Yorker cartoons. Mankoff also usually contributed a short article to each book, describing some aspect of the cartooning process or the methods used to select cartoons for the magazine. He left the magazine in 2017.[38]

The New Yorker's stable of cartoonists has included many important talents in American humor, including Charles Addams, Peter Arno, Charles Barsotti, George Booth, Roz Chast, Tom Cheney, Sam Cobean, Leo Cullum, Richard Decker, Pia Guerra, J. B. Handelsman, Helen E. Hokinson, Pete Holmes, Ed Koren, Reginald Marsh, Mary Petty, George Price, Charles Saxon, Burr Shafer, Otto Soglow, William Steig, Saul Steinberg, James Stevenson, James Thurber, and Gahan Wilson.

Many early New Yorker cartoonists did not caption their cartoons. In his book The Years with Ross, Thurber describes the newspaper's weekly art meeting, where cartoons submitted over the previous week were brought up from the mail room to be looked over by Ross, the editorial department, and a number of staff writers. Cartoons were often rejected or sent back to artists with requested amendments, while others were accepted and captions were written for them. Some artists hired their own writers; Hokinson hired James Reid Parker in 1931. Brendan Gill relates in his book Here at The New Yorker that at one point in the early 1940s, the quality of the artwork submitted to the magazine seemed to improve. It later was found out that the office boy (a teenaged Truman Capote) had been acting as a volunteer art editor, dropping pieces he did not like down the far end of his desk.[39]

Several of the magazine's cartoons have reached a higher plateau of fame. One 1928 cartoon drawn by Carl Rose and captioned by E. B. White shows a mother telling her daughter, "It's broccoli, dear". The daughter responds, "I say it's spinach and I say the hell with it". The phrase "I say it's spinach" entered the vernacular, and three years later, the Broadway musical Face the Music included Irving Berlin's song "I Say It's Spinach (And the Hell with It)".[40] The catchphrase "back to the drawing board" originated with the 1941 Peter Arno cartoon showing an engineer walking away from a crashed plane, saying, "Well, back to the old drawing board".[41][42]

The most reprinted is Peter Steiner's 1993 drawing of two dogs at a computer, with one saying, "On the Internet, nobody knows you're a dog". According to Mankoff, Steiner and the magazine have split more than $100,000 in fees paid for the licensing and reprinting of this single cartoon, with more than half going to Steiner.[43][44]

Over seven decades, many hardcover compilations of New Yorker cartoons have been published, and in 2004, Mankoff edited The Complete Cartoons of The New Yorker, a 656-page collection with 2,004 of the magazine's best cartoons published during 80 years, plus a double CD set with all 68,647 cartoons ever published in the magazine.[45] This features a search function allowing readers to search for cartoons by cartoonist's name or year of publication. The newer group of cartoonists in recent years includes Pat Byrnes, J. C. Duffy, Liana Finck, Emily Flake, Robert Leighton, Michael Maslin, Julia Suits, and P. C. Vey. Will McPhail cited his beginnings as "just ripping off Calvin and Hobbes, Bill Watterson, and doing little dot eyes".[46] The notion that some New Yorker cartoons have punchlines so oblique as to be impenetrable became a subplot in the Seinfeld episode "The Cartoon",[47] as well as a playful jab in The Simpsons episode "The Sweetest Apu".[citation needed]

In April 2005, the magazine began using the last page of each issue for "The New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest". Captionless cartoons by The New Yorker's regular cartoonists are printed each week. Captions are submitted by readers, and three are chosen as finalists. Readers then vote on the winner. Anyone age 13 or older can enter or vote. At first, the winner received a print of the cartoon (with the winning caption) signed by the artist who drew the cartoon, but this practice ceased.[48] In 2017, after Bob Mankoff left the magazine, Emma Allen became its youngest and first female cartoon editor.[49]

Comics journalism

Since 1993, the magazine has published occasional stories of comics journalism (alternately called "sketchbook reports")[50] by such cartoonists as Marisa Acocella Marchetto, Barry Blitt, Sue Coe, Robert Crumb and Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Jules Feiffer, Ben Katchor, Carol Lay, Gary Panter, Art Spiegelman, Mark Alan Stamaty, and Ronald Wimberly.[51]

Crosswords and puzzles

In April 2018, The New Yorker launched a crossword puzzle series with a weekday crossword published every Monday. Subsequently, it launched a second, weekend crossword that appears on Fridays and relaunched cryptic puzzles that were run in the magazine in the late 1990s. In June 2021, it began publishing new cryptics weekly.[52] In July 2021, The New Yorker introduced Name Drop, a trivia game, which is posted online weekdays.[53] In March 2022, The New Yorker moved to publishing online crosswords every weekday, with decreasing difficulty Monday through Thursday and themed puzzles on Fridays.[54] The puzzles are written by a rotating stable of 13 constructors. They integrate cartoons into the solving experience. The Christmas 2019 issue featured a crossword puzzle by Patrick Berry that had cartoons as clues, with the answers being captions for the cartoons. In December 2019, Liz Maynes-Aminzade was named The New Yorker's first puzzles and games editor.[citation needed]

Eustace Tilley

The magazine's first cover illustration, depicting a dandy peering at a butterfly through a monocle, was drawn by Rea Irvin, the magazine's first art editor. It was based on an 1834 caricature of the Count d'Orsay that appeared as an illustration in the 11th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica.[55] The character on the original cover, now known as Eustace Tilley, was created for The New Yorker by Corey Ford. The hero of a series titled "The Making of a Magazine", which began on the inside front cover of the August 8 issue that first summer, Tilley was a younger man than the figure on the original cover. His top hat was of a newer style, without the curved brim. He wore a morning coat and striped formal trousers. Ford borrowed Eustace Tilley's last name from an aunt—he had always found it vaguely humorous[citation needed]. He selected "Eustace" for euphony.[56]

The character has become a kind of mascot for The New Yorker, frequently appearing in its pages and on promotional materials. Traditionally, Irvin's original Tilley cover illustration is used every year on the issue closest to the anniversary date of February 21, though on several occasions a newly drawn variation has been substituted.[57]

Covers

The magazine is known for its illustrated and often topical covers. As of 2025, only two covers have featured photography.[58]

"View of the World" cover

Saul Steinberg created 85 covers and 642 internal drawings and illustrations for the magazine. His most famous work is probably the cover for issue March 29, 1976,[59] featuring an illustration, most often called "View of the World from 9th Avenue", sometimes called "A Parochial New Yorker's View of the World" or "A New Yorker's View of the World", which depicts a map of the world as seen by self-absorbed New Yorkers.

The illustration is split in two, with the bottom half showing Manhattan's 9th Avenue, 10th Avenue, and the Hudson River, and the top half depicting the rest of the world. The rest of the US is the size of the three New York City blocks and is drawn as a square, with a thin brown strip along the Hudson representing "Jersey", the names of five cities (Los Angeles; Washington, D.C.; Las Vegas; Kansas City; and Chicago) and three states (Texas, Utah, and Nebraska) scattered among a few rocks for the U.S. beyond New Jersey. The Pacific Ocean, perhaps half again as wide as the Hudson, separates the US from three flattened land masses labeled China, Japan and Russia.

The illustration—depicting New Yorkers' self-image of their place in the world, or perhaps outsiders' view of New Yorkers' self-image—inspired many similar works, including the poster for the 1984 film Moscow on the Hudson; that movie poster led to a lawsuit, Steinberg v. Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc., 663 F. Supp. 706 (S.D.N.Y. 1987), which held that Columbia Pictures violated the copyright that Steinberg held.

The cover was later satirized by Barry Blitt for the cover of The New Yorker on October 6, 2008, featuring Sarah Palin looking out of her window seeing only Alaska, with Russia in the far background.[60] The cover of the March 21, 2009, issue of The Economist, titled "How China sees the World", is an homage to Steinberg, depicting the viewpoint from Beijing's Chang'an Avenue instead of Manhattan.[61]

9/11

Hired by Tina Brown in 1992, Art Spiegelman worked for The New Yorker for ten years, but resigned a few months after the September 11 terrorist attacks. Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly received wide acclaim for their cover for the issue from September 24, 2001; it was voted as being among the top ten magazine covers of the past 40 years by the American Society of Magazine Editors:

The cover appears to be totally black, but upon close examination it reveals the silhouettes of the World Trade Center towers in a darker shade of black. In some situations, the ghost images become visible only when the magazine is tilted toward a light source.[62] In September 2004, Spiegelman reprised the image on the cover of his book In the Shadow of No Towers.

"New Yorkistan"

In December 2001, the magazine printed a cover by Maira Kalman and Rick Meyerowitz showing a map of New York in which neighborhoods are labeled with humorous names reminiscent of Middle Eastern and Central Asian place names and referencing the neighborhood's real name or characteristics (e.g., "Fuhgeddabouditstan", "Botoxia"). The cover had cultural resonance in the wake of September 11, and became a popular print and poster.[63][64]

Controversial covers

Crown Heights in 1993

For the 1993 Valentine's Day issue, the cover by Spiegelman depicted a black woman and a Hasidic Jewish man kissing, referencing the Crown Heights riot of 1991.[65][66] The cover was criticized by black and Jewish observers.[67] Jack Salzman and Cornel West called reaction to the cover the magazine's "first national controversy".[68]

2008 Obama cover satire and controversy

On July 21, 2008, "The Politics of Fear", a cartoon by Barry Blitt, was featured on the cover of The New Yorker, depicting then presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Barack Obama in the turban and shalwar kameez typical of many Muslims, fist bumping with his wife, Michelle, portrayed with an Afro and wearing camouflage trousers with an assault rifle slung over her back. They are standing in the Oval Office, with a portrait of Osama bin Laden hanging on the wall and an American flag burning in the fireplace.[69] This parody was inspired by Fox News host E. D. Hill's paraphrase of an internet comment that asked whether a gesture the Obamas made was a "terrorist fist jab".[70][71] Later, Hill's contract was not renewed.[72]

Many New Yorker readers saw the image as a lampoon of "The Politics of Fear", its title. Some Obama supporters, as well as his presumptive Republican opponent, John McCain, accused the magazine of publishing an incendiary cartoon whose irony could be lost on some readers. Editor David Remnick felt the image's obvious excesses rebuffed the concern it could be misunderstood.[73][74] "The intent of the cover", he said, "is to satirize the vicious and racist attacks and rumors and misconceptions about the Obamas that have been floating around in the blogosphere and are reflected in public opinion polls. What we set out to do was to throw all these images together, which are all over the top and to shine a kind of harsh light on them, to satirize them."[75] Obama said, "Well, I know it was The New Yorker's attempt at satire... I don't think they were entirely successful". He pointed to his efforts to debunk the allegations the cover depicted, saying that the allegations were "actually an insult against Muslim-Americans".[76][77] The Daily Show continued The New Yorker cover's argument about Obama stereotypes with a piece showcasing clips containing such stereotypes culled from legitimate news sources.[78] On October 3, 2008, Entertainment Weekly magazine published a parody of the cover, featuring Jon Stewart as Barack and Stephen Colbert as Michelle.[79]

New Yorker covers are sometimes unrelated to the contents, or only tangentially related. The article about Obama in the issue with Blitt's cover did not discuss the attacks and rumors, but rather Obama's career. The magazine later endorsed Obama for president.

2013 Bert and Ernie cover

On July 8, 2013, The New Yorker featured a cover image by artist Jack Hunter, titled "Moment of Joy", depicting Sesame Street characters Bert and Ernie; the issue in particular covered the Supreme Court decisions on the Defense of Marriage Act and California Proposition 8.[80] Bert and Ernie have long been rumored in urban legend to be romantic partners, but Sesame Workshop has denied this, saying they are merely "puppets" and have no sexual orientation.[81] Slate criticized the cover, which shows Ernie leaning on Bert's shoulder as they watch a television with the Supreme Court justices on the screen, saying, "it's a terrible way to commemorate a major civil-rights victory for gay and lesbian couples". The Huffington Post, meanwhile, said it was "one of [the magazine's] most awesome covers of all time".[82]

2023 "Race for Office" cover

The cover from October 2, 2023, titled "The Race for Office", depicts top politicians—Donald Trump, Mitch McConnell, Nancy Pelosi, and Joe Biden—running the titular race for office with walkers. Many had questioned the mental and physical states of these and other older politicians, particularly those who have run for reelection.[83][84][85][86] While many acknowledged the cover as satirizing this issue, others criticized the "ableism and ageism" of mocking older people and those who use walkers.[87][88] The New Yorker said the cover "portrays the irony and absurdity of the advanced-age politicians currently vying for our top offices".[89]

Style

The New Yorker's signature display typeface, used for its nameplate and headlines and the masthead above "The Talk of the Town" section, is named Irvin, named after its creator, the designer-illustrator Rea Irvin.[90] The body text of all articles is set in Adobe Caslon.[91]

One uncommonly formal feature of the magazine's in-house style is the placement of diaeresis marks in words with repeating vowels—such as reëlected, preëminent, and coöperate—in which the two vowel letters indicate separate vowel sounds.[92][93] The magazine also continues to use a few spellings that are otherwise little used in American English, such as fuelled, focussed, venders, teen-ager,[94] traveller, marvellous, carrousel,[95] and cannister.[96]

The magazine also spells out the names of numerical amounts, such as "two million three hundred thousand dollars" instead of "$2.3 million", even for very large figures.[97]

Fact-checking

In 1927, The New Yorker ran an article about Edna St. Vincent Millay that contained multiple factual errors, and her mother threatened to sue the publication for libel.[98] Consequently, the magazine developed extensive fact-checking procedures, which became integral to its reputation as early as the 1940s.[99] In 2019, the Columbia Journalism Review said that "no publication has been more consistently identified with its rigorous fact-checking".[98] As of 2025, about 30 people work in the fact-checking department.[100]

At least two defamation lawsuits have been filed over articles published in the magazine, though neither were won by the plaintiff. Two 1983 articles by Janet Malcolm about Sigmund Freud's legacy led to a lawsuit from writer Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, who claimed that Malcolm had fabricated quotes attributed to him.[101] After years of proceedings and appeals, a jury found in Malcolm's favor in 1994.[102] In 2010, David Grann wrote an article for the magazine about art expert Peter Paul Biro that scrutinized and expressed skepticism about Biro's stated methods to identify forgeries.[103] Biro sued The New Yorker for defamation, alongside multiple other news outlets that reported on the article, but the case was summarily dismissed.[103][104][105][106]

Readership

The New Yorker is read nationwide, with 53% of its circulation in the top 10 U.S. metropolitan areas.[citation needed]

According to a 2009 survey-based estimate of magazine audiences by MediaMark Research, the average New Yorker reader was 47.8 years old, with a household income of $91,359.[107] In the same period, the average household income in the United States was $58,898.[107]

Politically, the magazine's readership holds generally liberal views. According to a 2014 Pew Research Center survey, 77% of The New Yorker's readers have left-of-center political values, and 52% of them hold "consistently liberal" political values.[108]

List of books about The New Yorker

- Ross and The New Yorker by Dale Kramer (1951)

- The Years with Ross by James Thurber (1959)

- Ross, The New Yorker and Me by Jane Grant (1968)

- Here at The New Yorker by Brendan Gill (1975)

- About the New Yorker and Me by E.J. Kahn (1979)

- Onward and Upward: A Biography of Katharine S. White by Linda H. Davis (1987)

- At Seventy: More about The New Yorker and Me by E. J. Kahn (1988)

- Katharine and E. B. White: An Affectionate Memoir by Isabel Russell (1988)

- The Last Days of The New Yorker by Gigi Mahon (1989)

- The Smart Magazines: Fifty Years of Literary Revelry and High Jinks at Vanity Fair, the New Yorker, Life, Esquire, and the Smart Set by George H. Douglas (1991)

- Genius in Disguise: Harold Ross of the New Yorker by Thomas Kunkel (1997)

- Here But Not Here: My Life with William Shawn and The New Yorker by Lillian Ross (1998)

- Remembering Mr. Shawn's New Yorker: The Invisible Art of Editing by Ved Mehta (1998)

- Some Times in America: And a Life in a Year at The New Yorker by Alexander Chancellor (1999)

- The World Through a Monocle: The New Yorker at Midcentury by Mary F. Corey (1999)

- About Town: The New Yorker and the World It Made by Ben Yagoda (2000)

- Covering the New Yorker: Cutting-Edge Covers from a Literary Institution by Françoise Mouly (2000)

- Defining New Yorker Humor by Judith Yaross Lee (2000)

- Gone: The Last Days of The New Yorker, by Renata Adler (2000)

- Letters from the Editor: The New Yorker's Harold Ross edited by Thomas Kunkel (2000; letters covering the years 1917 to 1951)

- New Yorker Profiles 1925–1992: A Bibliography compiled by Gail Shivel (2000)

- NoBrow: The Culture of Marketing – the Marketing of Culture by John Seabrook (2000)

- Fierce Pajamas: An Anthology of Humor Writing from The New Yorker by David Remnick and Henry Finder (2002)

- Christmas at The New Yorker: Stories, Poems, Humor, and Art (2003)

- A Life of Privilege, Mostly by Gardner Botsford (2003)

- Maeve Brennan: Homesick at The New Yorker by Angela Bourke (2004)

- Better than Sane by Alison Rose(2004)

- Let Me Finish by Roger Angell (Harcourt, 2006)

- The Receptionist: An Education at The New Yorker by Janet Groth (2012)

- My Mistake: A Memoir by Daniel Menaker (2013)

- Between You & Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen by Mary Norris (2015)

- Cast of Characters: Wolcott Gibbs, E. B. White, James Thurber and the Golden Age of The New Yorker by Thomas Vinciguerra (2015)

- Peter Arno: The Mad, Mad World of The New Yorker's Greatest Cartoonist by Michael Maslin (2016)

Films about The New Yorker

In Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle, a film about the Algonquin Round Table starring Jennifer Jason Leigh as Dorothy Parker, Sam Robards portrays founding editor Harold Ross trying to drum up support for his fledgling publication.

The magazine's former editor, William Shawn, is portrayed in Capote (2005), Infamous (2006), and Hannah Arendt (2012).

The 2015 documentary Very Semi-Serious, directed by Leah Wolchok and produced by Wolchok and Davina Pardo (Redora Films), presents a behind-the-scenes look at the cartoons of The New Yorker.[109]

List of films about The New Yorker

- Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle (1994)

- James Thurber: The Life and Hard Times (2000)

- Joe Gould's Secret (2000)

- Top Hat and Tales: Harold Ross and the Making of the New Yorker (2001)[110][111]

- Very Semi-Serious (2015)

- Wes Anderson's The French Dispatch (2021) is an overt homage to the magazine;[112] the film consists of several long-form "stories", all in the style of various New Yorker contributors.

- The New Yorker at 100 (2025)[113]

See also

- List of The New Yorker contributors

- The New Yorker Festival

- The New Yorker Radio Hour, a radio program carried by public radio stations

Explanatory notes

- The caricature, or a variation of it, appeared on the cover of every anniversary issue until 2017, when, in protest of Executive Order 13769, Tilley was not depicted (although a variation appeared two issues later).[1][2]

References

- "The New Yorker February 13 & 20, 2017 Issue". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 10, 2018. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- "The New Yorker March 6, 2017 Issue". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 10, 2018. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- "The New Yorker media kit". condenast.com. Archived from the original on October 21, 2014.

- "Statement of Ownership". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. October 6, 2025. p. 61. Retrieved October 1, 2025.

- Cain, Sarah (2015). "2:'We Stand Corrected': New Yorker Fact-checking and the Business of American Accuracy". In Green, Fiona (ed.). Writing for The New Yorker: Critical Essays on an American Periodical. Oxford University Press.

- Temple, Emily (February 21, 2018). "20 Iconic New Yorker Covers from the Last 93 Years". Literary Hub. Archived from the original on February 23, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- Norris, Mary (May 10, 2015). "How I proofread my way to Philip Roth's heart". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 12, 2018. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

It has been more than 20 years since I became a page OK'er—a position that exists only at the New Yorker, where you query-proofread pieces and manage them, with the editor, the author, a fact-checker, and a second proofreader, until they go to press.

- "Mary Norris: The nit-picking glory of the New Yorker's comma queen". TED. April 15, 2016. Archived from the original on July 28, 2018. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

Copy editing for The New Yorker is like playing shortstop for a major league baseball team—every little movement gets picked over by the critics ... E. B. White once wrote of commas in The New Yorker: 'They fall with the precision of knives outlining a body.'

- "Section 4: Demographics and Political Views of News Audiences". Pew Research Center. September 27, 2012. Archived from the original on May 11, 2024. Retrieved May 11, 2024.

- "The New Yorker Wins Three 2025 Pulitzer Prizes". The New Yorker. May 5, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- "Timeline", The New Yorker. Archived November 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- Johnson, Dirk (August 5, 1999). "Dubuque Journal; The Slight That Years, All 75, Can't Erase". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 4, 2024. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- Franklin, Ruth (June 25, 2013). "'The Lottery' Letters". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- "Pray and Grow Rich". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. October 11, 2004. Archived from the original on April 2, 2023. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- "The Secret Life of Time". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. December 11, 2016. Archived from the original on January 18, 2024. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- "The Bad Mother". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. August 2, 2004. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- Easley, Greg (October 1995). "The New Yorker: When a Magazine Wins Awards But Loses Money, the Only Success is the Editor's Private One". Spy. Archived from the original on June 4, 2024. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- Mahon, Gigi (September 10, 1989). "S.I. Newhouse and Conde Nast; Taking Off The White Gloves". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 26, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- Harper, Jennifer (July 13, 1998). "New Yorker Magazine Names New Editor". The Washington Times. Knight Ridder/Tribune Business News. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2016 – via HighBeam Research.

- Arendt, Hannah (February 8, 1963). "Eichmann in Jerusalem". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the original on September 21, 2019. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- "Eichmann in Jerusalem by Hannah Arendt – Reading Guide: 9780143039884". PenguinRandomhouse.com. Archived from the original on December 22, 2023. Retrieved December 22, 2023.

- "A relaunch for the New Yorker, with high stakes". Politico. July 21, 2014. Archived from the original on January 1, 2024. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- Robertson, Katie (June 16, 2021). "New Yorker Union Reaches Deal With Condé Nast After Threatening to Strike". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021.

- Lee, Judith Yaross (2000). Defining New Yorker Humor. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 12. ISBN 9781578061983.

brooklynite

- Overbey, Erin (January 31, 2013). "A New Yorker for Brooklynites". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- "Erskine Gwynne, 49, Wrote Book on Paris". The New York Times. May 6, 1948. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- Vonnegut, Kurt (1988). Allen, William Rodney (ed.). Conversations with Kurt Vonnegut. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. pp. 163–164. ISBN 9780878053575.

- Wolfe, Tom, "Foreword: Murderous Gutter Journalism", in Hooking Up. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2000.

- Rosenblum, Joseph (2001). "About Town". In Wilson, John D.; Steven G. Kellman (eds.). Magill's Literary Annual 2001: Essay-Reviews of 200 Outstanding Books Published in the United States During 2000. Pasadena, CA: Salem Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-89356-275-0.

- "The Choice". The New Yorker. October 25, 2004. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- "The Choice". The New Yorker. November 1, 2004. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- "The Choice". The New Yorker. October 13, 2008. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- "The Choice". The New Yorker. October 29, 2012. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- "The New Yorker Endorses Hillary Clinton". The New Yorker. October 31, 2016. Archived from the original on April 15, 2020. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- "The New Yorker Endorses a Biden Presidency". The New Yorker. October 5, 2020. Archived from the original on October 5, 2020. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- "Harris for President". The New Yorker. October 7, 2024. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

- "Lee Lorenz". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- Cavna, Michael. "Bob Mankoff named humor editor for Esquire one day after exiting the New Yorker", Archived January 29, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Washington Post (May 1, 2017).

- Gill, Brendan. Here at The New Yorker. New York: Berkley Medallion Press, 1976. p. 341.

- Gill (1976), p. 220.

- "Michael Maslin – Finding Arno". Archived from the original on September 17, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- "CBR.com – The World's Top Destination For Comic, Movie & TV news". Archived from the original on January 31, 2011. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- Fleishman, Glenn (December 14, 2000). "Cartoon Captures Spirit of the Internet". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- "Peter Steiner's 'On the Internet, nobody knows you're a dog.'". Archived from the original on October 29, 2005. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- Mankoff, Robert, ed. (2004). The Complete Cartoons of The New Yorker (First hardcover ed.). New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publisher. ISBN 9781579123222. OCLC 1547920310. Retrieved November 3, 2025.

- "Freedom and Space: In Conversation with New Yorker Cartoonist Will McPhail". Cleveland Review of Books. July 22, 2021. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- Mankoff, Robert (July 11, 2012). "I Liked the Kitty". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the original on July 15, 2023. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- "Caption Contest Rules". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on July 12, 2018. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- Cavna, Michael (October 6, 2021). "Emma Allen is redefining what a New Yorker cartoon can be". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- McGee, Kathleen. "Spiegelman Speaks: Art Spiegelman is the author of Maus for which he won a special Pulitzer in 1992. Kathleen McGee interviewed him when he visited Minneapolis in 1998" Archived November 8, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Conduit (1998).

- Williams, Kristian. "The Case for Comics Journalism", Columbia Journalism Review Vol. 43, Iss. 6, (Mar/Apr 2005), pp. 51–55.

- "Announcing an All-New Weekly Cryptic Crossword from The New Yorker". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- "Introducing Name Drop: a Daily Trivia Game from The New Yorker". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on September 9, 2022. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- "You Can Now Play The New Yorker Crossword Every Weekday". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on September 9, 2022. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- "Eustace Tilley". March 29, 2010. Archived from the original on August 17, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- Kunkel, Thomas (June 1996). Genius in Disguise. Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 512. ISBN 9780786703234.

- Mouly, Françoise (February 16, 2015). "Cover Story: Nine for Ninety". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on August 4, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- Whiddington, Richard (August 26, 2025). "Cindy Sherman Slips Into Character for the New Yorker's Centenary Cover". Artnet. Retrieved August 29, 2025.

- "New Yorker March 29, 1976 by Saul Steinberg". Condé Nast. Archived from the original on March 4, 2022. Retrieved April 5, 2022.

- "New Yorker Cover – 10/6/2008 at The New Yorker Store". Newyorkerstore.com. October 6, 2008. Archived from the original on January 18, 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- "Issue Cover for March 21, 2009". The Economist. March 21, 2009. Archived from the original on February 25, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- "ASME's Top 40 Magazine Covers of the Last 40 Years – ASME". Archived from the original on November 4, 2018. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- "The New Yorker uncovers an unexpected profit center – Ancillary Profits – by licensing cover illustrations". Folio: The Magazine for Magazine Management. February 2002. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016.

- Daniel Grand (February 12, 2004). "A Print by Any Other Name..." OpinionJournal. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- Campbell, James (August 28, 2004). "Drawing pains". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- Chideya, Farai (July 15, 2008). "Cartoonist Speaks His Mind on Obama Cover: News & Views". NPR. Archived from the original on April 13, 2010. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- Shapiro, Edward S. (2006). Crown Heights: Blacks, Jews, and the 1991 Brooklyn Riot. UPNE. p. 211.

- Jack Salzman; Cornel West (1997). Struggles in the Promised Land: Towards a History of Black-Jewish Relations in the United States. Oxford University Press US. p. 373. ISBN 978-0-19-508828-1. Archived from the original on June 4, 2024. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- Kugler, Sara (July 14, 2008). "New Yorker cover stirs controversy". Canoe.ca. Associated Press. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

{{cite news}}:|archive-url=is malformed: timestamp (help) - Beam, Christopher (July 14, 2008). "The 'Terrorist Fist Jab' and Me". Slate. Archived from the original on December 27, 2009. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

- "Fox News anchor calls the Obamas' fist pound 'a terrorist fist jab'". Think Progress. Archived from the original on June 10, 2008. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- "Fox News Changes: 'Terrorist Fist Jab' Anchor E.D. Hill Loses Her Show, Laura Ingraham In At 5PM" Archived July 23, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Huffington Post, June 18, 2008.

- "Was it satire?". The Hamilton Spectator. July 19, 2008. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- "Barack Obama New Yorker Cover Branded Tasteless". Marie Claire. July 15, 2008. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- Tapper, Jake (July 14, 2008). "New Yorker Editor David Remnick Talks to ABC News About Cover Controversy". ABC News. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- "Democrats' bus heads South to sign up new voters". The Boston Globe. July 16, 2008. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- Tapper, Jake (July 13, 2008). "Obama Camp Hammers New 'Ironic' New Yorker Cover Depicting Conspiracists' Nightmare of Real Obamas". Political Punch. ABC News. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- "Obama Cartoon" Archived February 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Daily Show, July 15, 2008.

- Wolk, Josh (September 30, 2008). "Entertainment Weekly October 3, 2008, Issue #1014 cover". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 27, 2009. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- Mouly, Francoise; Kaneko, Mina. "Cover Story: Bert and Ernie's 'Moment of Joy'". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on June 25, 2014. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

'It's amazing to witness how attitudes on gay rights have evolved in my lifetime,' said Jack Hunter, the artist behind next week's cover

- Mikkelson, Barbara and David P. (August 6, 2007). "Open Sesame". Urban Legends Reference Pages. Barbara and David P. Mikkelson. Archived from the original on April 5, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

The Children's Television Workshop has steadfastly denied rumors about Bert and Ernie's sexual orientation...

- Christina Ng. "Bert and Ernie Cuddle Over Supreme Court Ruling". ABC News. Archived from the original on July 1, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- Seddiq, Oma. "The top US general 'was certain that Trump had gone into a serious mental decline' after the 2020 election, book says". Business Insider. Archived from the original on October 10, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- "Mitch McConnell freezes for second time during press event". BBC News. August 30, 2023. Archived from the original on October 10, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- Mascaro, Lisa (September 8, 2023). "Nancy Pelosi says she'll seek House reelection in 2024, dismissing talk of retirement at age 83". AP News. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- Montanaro, Domenico (May 23, 2023). "More than 6 in 10 say Biden's mental fitness to be president is a concern, poll finds". NPR. Archived from the original on October 10, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- Moran, Lee (September 26, 2023). "New Yorker Slammed For Cover Depicting Biden, Trump With Walkers". HuffPost. Archived from the original on October 9, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- Daunt, Tina (September 25, 2023). "New Yorker Cover Showing Top US Politicians Using Walkers Draws Cries of Ageism: 'Disgusting and Vulgar'". TheWrap. Archived from the original on October 10, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- Mouly, Françoise (September 25, 2023). "Barry Blitt's 'The Race for Office'". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the original on October 10, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- "Home". Allworth Press. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015.

- Gopnik, Adam (February 9, 2009). "Postscript". The New Yorker. p. 35.

- Norris, Mary (April 26, 2012). "The Curse of the Diaeresis". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- Boynton, Andrew (March 10, 2025). "The New Yorker House Style Joins the Internet Age". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 15, 2025.

...[I]t should be noted that the diaeresis...has overwhelming support at the magazine, and will remain.

- Stillman, Sarah (August 27, 2012). "The Throwaways". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 12, 2014. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- Norris, Mary (April 25, 2013). "The Double L". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- Norris, Mary (April 12, 2012). "In Defense of 'Nutty' Commas". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- Davidson, Amy (March 16, 2011). "Hillary Clinton Says 'No'". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- Dickey, Colin (Fall 2019). "The Rise and Fall of Facts". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on December 7, 2019. Retrieved December 7, 2019.

- Yagoda, Ben (2001). About Town: The New Yorker and the World It Made. Da Capo Press. pp. 202–3. ISBN 978-0-306-81023-7.

- McIntosh, Fergus (January 11, 2025). "What's a Fact, Anyway?". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- Carmody, Deirdre (May 30, 1993). "Despite Malcolm Trial, Editors Elsewhere Vouch for Accuracy of Their Work". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 5, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- Boynton, Robert (November 28, 1994). "Till Press Do Us Part: The Trial of Janet Malcolm and Jeffrey Masson". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- Samaha, Albert (August 5, 2013). "Art Authenticator Loses Defamation Suit Against the New Yorker". The Village Voice Blog. Archived from the original on January 11, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- Julia Filip, "Art Analyst Sues The New Yorker" Archived July 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Courthouse News Service (July 1, 2011).

- Dylan Byers, "Forensic Art Expert Sues New Yorker – Author Wants $2 million for defamation over David Grann piece" Archived August 15, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Adweek, June 30, 2011.

- 11 Civ. 4442 (JPO) Peter Paul Biro v. ... David Grann ... Archived February 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, United States District Court – Southern District of New York

- "Magazines – Audience", The State of the News Media 2010, Pew Research Center Project for Excellence in Journalism, archived from the original on March 18, 2011, retrieved March 9, 2025,

Readers of news magazines tend to be both older and wealthier than the population as a whole.

- "Where New Yorker's Audience Fits on the Political Spectrum". Pew Research Center's Journalism Project. October 21, 2014. Archived from the original on June 4, 2018. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- Hoffman, Jordan (November 19, 2015). "Very Semi-Serious review – droll doc goes inside the New Yorker's cartoon shed". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- Caryn James (May 13, 2001). "Neighborhood Report: CRITIC'S VIEW; How The New Yorker Took Wing In Its Larval Years With Ross". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- Quick Vids by Gary Handman, American Libraries, May 2006.

- Overbey, Erin (September 24, 2021). "The New Yorker Writers and Editors Who Inspired The French Dispatch". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on February 14, 2024. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- Fienberg, Daniel (August 30, 2025). "'The New Yorker at 100' Review: Netflix Doc Is Entertaining and Star-Studded, but the Storied Magazine Deserved More Depth". The Hollywood Reporter.

External links

- The New Yorker

- 1925 comics debuts

- 1925 establishments in New York City

- Comics magazines published in the United States

- Condé Nast magazines

- Culture of New York City

- Investigative journalism

- Literary magazines published in the United States

- Magazines established in 1925

- Magazines published in New York City

- News magazines published in the United States

- Pulitzer Prize for Public Service winners

- Weekly magazines published in the United States